You no talk good: how dialogue defines the games we play

As a person who traffics in the written word for a living, I find the way dialogue and storytelling are being devalued in games upsetting. When a recent assignment had me researching the best MMOs, the way language so often takes a bottom rung position after gameplay, graphics, and practically every other building block of modern video games really hit home.

But just because language, and especially dialogue, is being deprioritized by a number of developers and publishers doesn’t mean it’s unimportant. While it’s true that for a number of games (genres even) storytelling and character building are - and should be - secondary or tertiary concerns, the strength of writing sends a number of messages about quality and polish. No one needs a robust narrative in their mobile Solitaire clone, but if the writing that’s there (even if it’s just in menus or under button prompts) is chock full of misspellings and sub-grade-school grammar, the game it’s representing immediately looks rushed and shoddy.

This is even more crucial in games that do rely heavily on spoken and written dialogue to tell their stories, and those games aren’t just the usual suspects (RPGs, adventure games, and visual novels). We often don’t think about it, but every piece of incidental dialogue in every massive open world game, online multiplayer shooter, and MOBA was written by someone (or improvised in a voice recording booth, which is a kind of writing). The random barks from pedestrians in Watch Dogs 2 or Mafia 3, the specific callouts that happen when two heroes meet in Marvel Heroes, the voiceover that calls out falling towers or slain heroes in Dota 2; at some point these were crafted to suit a specific purpose.

And that’s just the subtle stuff. Obviously, the majority of big plot points, the major themes and tone of most games, are built from - or at least heavily influenced by - dialogue. So what are the keys to getting it right, and what are some of the best-(or worst-)in-class examples of games that have nailed it (or utterly botched it)?

The good

Games have always relied on a foundation of words and ideas to conceive their worlds and animate them with life. In many ways this was even more important during gaming’s infancy, when deep RPGs and other narrative-heavy experiences were hamstrung by crude graphics constructed from a handful of rough pixels. Many of these early games painted their worlds with words as much as with visuals, and the best of them clung to that old axiom - show, don’t tell. The idea that characters and their interactions should shape your world, instead of an omniscient narrator spelling everything out, is especially important in games, where players inhabit the characters interactively.

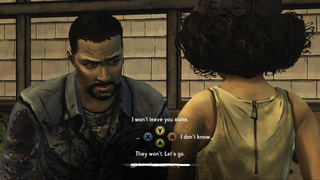

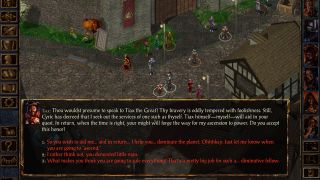

The Infinity Engine games from Black Isle (and some of the games they inspired) spring to mind as great early examples of dialogue done right. Some of the characters in titles like Baldur’s Gate (and the sequel, Shadows of Amn) or Icewind Dale still resonate today because of the verve of their personalities and the way they perfectly suit their setting and roles. The writers of these games recognized that they were writing melodrama, and they created characters that fit their grandiose narrative.

It’s been said it takes a sociopath to believe they can save the world (and to therefore actually go about saving it), and many of the heroes in those Infinity Engine games fit the bill in dramatic, and sometimes hilarious, fashion. The exchanges of dialogue between these characters, from the off-hand battle shouts to the comprehensive conversation trees, make the experiencing of shepherding them to their destinies feel more like embarking on an adventure with friends than manipulating a party of faceless composites of stats and gear. But don’t take my word for it, try shouting “Go for the eyes, Boo! Go for the eyes!” in any crowded PAX hall and observe the reaction.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Of course, more modern games rely heavily on dialogue to propel their narratives as well, from the gritty pathos of Spec Ops: The Line’s haunted, damned Kurtz-alike Colonel John Konrad to the mania, dyspraxic twitching, and fits of random violence that characterize Far Cry 3’s Vaas Montenegro. Some of the most chilling moments in games are the result of seeing too far into the disturbed mind of a deeply mentally unhinged individual, hearing them calmly lay out their distorted justifications of some of the horrors they’ve inflicted on the player or his allies. As mediums like film had to learn as they evolved out of their awkward adolescence, games too had to come to grips with the idea that characters are most effective when they’re written like actual, three-dimensional human beings and not cardboard standees and stereotypes.

The bad

While positive examples like the ones I mentioned can teach important lessons (write characters to suit your story and setting, treat your dialogue like something that would come out of the mouth of a real human being), examples of what not to do can also be instructive. As my goal here isn’t to take pot shots at other writers or tear down games which - even when poorly written - often still have a lot to recommend them, I’ll paint with a broad brush here.

One of the cardinal sins of game dialogue is over-explaining. To some extent, this complements the idea that dialogue should sound like something you’d actually hear in the real world, and also with the idea that you should show, and not tell, your story. We’ve all played games where the characters addressing us are obviously just stand-ins for the writers or game designers, and are either explaining ad infinitum, in painfully precise detail, exactly what the game expects us to do next or how to use a mechanic to overcome an obstacle.

This is a personal appeal to game developers: please stop putting things like button prompts and massive walls of tutorial text in the mouths of your characters. That’s what pop up text boxes or help sections are for. And the same goes for lore and exposition; a character that serves the role of a fleshy encyclopedia, patiently detailing the important events and figures of your world, is awkward and unnecessary. The role of encyclopedias should be filled by, stay with me here, actual encyclopedias.

Another huge stumbling block for game dialogue is making every character in your world sound like a generic reprint of an exhausted trope. The daring, hyper-masculine knight, the damsel-in-distress, the wheedling coward comic relief. We’ve seen these characters, loved them, grew to despise them, and have thoroughly moved on from them. If you must start designing a character’s voice with a stereotype like these in mind, at least add a few additional dimensions, a few quirks or interesting wrinkles, that distinguish them from every other character written in that mold.

And finally, if we could finally do away with the painful phonetic dialogue (a crutch to add ‘flavor’ or a sense of regional dialect) and nonsense words (particularly prevalent amongst chibi characters or species in JRPGs), our medium would be a significantly less annoying one.

The ugly

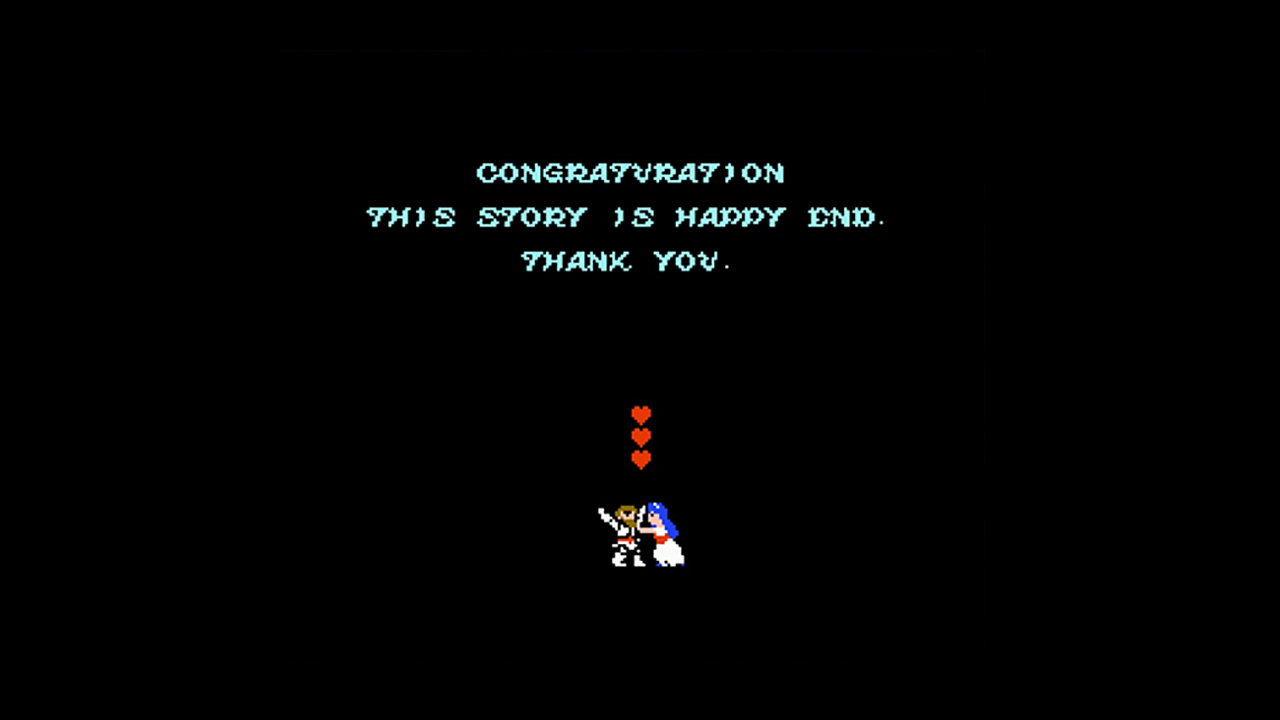

Beyond some of the bad habits and laziness that characterize the issues I outlined above, there are some dialogue issues that are just a deal-breaker. These include some of the budget title markers I mentioned early on, like poor spelling or typographical problems, but also include some of the phenomenon of incomplete or underfunded localization.

While bad localization has provided some of gaming’s most unintentionally hilarious moments (we’ve all sampled a Jill sandwich, been confused vis a vis the ownership of certain bases, or thrilled to an exceptional mastery of the art of unlocking), the majority of the time it’s just cringe-worthy. And occasionally, truly bad examples can lead to real frustration, like when some pseudo-English meant to guide us to the next objective is so broken we’re left with no clear idea of what to do next. But even that level of poor localization is more forgivable than when a native English speaker writes dialogue so awful that you assume it’s the product of a steep language barrier, and only later discover that it’s just the product of zero effort or, arguably, a flawed educational system.

The takeaway is that dialogue and conversation is much more fundamental in our experience of games than we often give it credit for, and we need to stop treating it like the ugly stepchild of this medium. Hopefully, as the march of progress continues to drive technology, and graphics and mechanics continue to become more complex and sophisticated, dialogue doesn’t get left behind. Otherwise... what will PAX attendees shout at one another in ten years time?

Alan Bradley was once a Hardware Writer for GamesRadar and PC Gamer, specialising in PC hardware. But, Alan is now a freelance journalist. He has bylines at Rolling Stone, Gamasutra, Variety, and more.

Inzoi dev says "highly inappropriate" bug that let you kill kids with your car has been patched out: "We are strengthening our internal review processes"

"30 years of history reside in our tape backups": PlayStation's building a game preservation mineshaft vault with 200 million files going back to a 1994 build of PS1 JRPG Arc the Lad