Why less is always more in game design

Although not without its good moments, structurally Castlevania: Lords of Shadow 2 is a shambles. A directionless, lurching mess of a thing, on the whole it bears little resemblance to the original game, hardly even seeming aware of what made the first Lords of Shadow work. Even now, several weeks after finishing it, I’m incredulous as to the final shape of the game, and even more bemused as to what went wrong.

To play through CLoS2 is to play through what feels like five or six stapled-together chunks of five or six separate, unpolished games, made by five or six different developers who never spoke to each other during the design process. It’s a game that doesn’t seem to know what it should be, and so throws as much shit at the wall as it can, in the hope that something will stick. As is always the result of that approach, all CLoS2 has to show for it is a rather shitty wall.

But while I can’t fathom the reasons for the debacle, the game’s resulting symptoms and specific failings are all too clear. In fact they’re entirely predictable. Because the simple fact is, in game design, there’s often an inverse relationship between the quality of content and the amount of different types of content. More is certainly not always more.

The difference comes from a basic early decision. Do you try to add value to your game by including a boat load of different gameplay mechanics and ideas, or do you focus on honing one or two? The latter approach invariably results in the best games, or at the very least the most coherent.

Right now you might be pondering upon just how correct that statement is. After all, today’s AAA games are vast, free-wheeling epics, full of side-quests, optional exploration and tangential content. But this point isn’t about the breadth of stuff in a game. It’s about the way that stuff is handled. Think about any of the best, most seemingly complex games you like. Then strip away all of the surface dressing, all the narrative bells and whistles, and think about what the game is really doing. In most cases you’ll find a restrained number of core play mechanics and principles, mixed up not by intermittent changes to their fundamental workings, but simply by the different ways they’re reinterpreted along the course of the game. Game mechanics themselves don’t fundamentally change, rather they’re refocused through differing external circumstances.

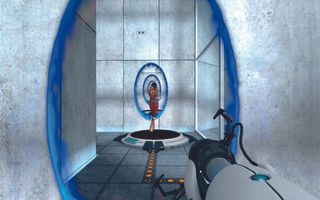

Portal? The function of the portal gun never changes, but more complex puzzle design forces a change in the way the player functions with the portal gun. Halo? The fundamentals of movement and shooting remain the same throughout, but different weapon effects and enemy behaviours make them feel utterly malleable from level to level. Assassin’s Creed 4? A vast world full of varied things to do, but interaction with that world always stems from the same fundamental traversal and combat principles laid out in the first game. It’s no coincidence that the later series’ sojourns into divergent mini-game territory have often been cited as its weakest elements.

The Mario series’ penchant (and by definition of Mario’s influence, that of countless other platformers) of providing a buffet of themed worlds--slippy, slidey ice and burny, melty lava being the two most popular flavours--might have become a derided trope, but its existence is both important and entirely reasonable. It’s one of the earliest and most ingeniously economical ways of executing the design process I’m talking about. Mario’s flawlessly honed handling never changes, but the altered properties of the levels around him eke differing play-styles from the control’s deceptive versatility. And at the same time, the evolving environments provide a neat sense of progression for Mario’s journey.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

As a direct comparison, look at early-Mario’s contemporaries in the glut of film-licensed games that filled the shelves during the ‘80s and ‘90s. All too often they attempted to translate a pre-written journey into gameplay by throwing in a new game style every other level--the platforming bit, the fighting bit, the driving bit, the shooting bit, etc.--becoming the proverbial jacks of far too many trades and delivering entirely forgettable gaming experiences.

Why is coherence so damn important? Because, in a nutshell, it simply makes for a more satisfying, immersive experience. Additionally, my reference to forgettability in that last paragraph was not simply an off-hand criticism. A more coherent game resonates in the mind long after a messy one has vanished from the mind like thought-mist in the breeze. Aside from the additional polish afforded by limiting the number of systems a game uses, restricting the number of plates being spun also makes the experience more believable.

It’s the same in film, or TV, or any medium really. Consistency breeds believability, and believability breeds resonance. An action hero who’s too capable, who’s a walking Swiss Army Knife capable of pulling out a new trick or ability to fit any given situation, just doesn’t hold true. Similarly, if a character’s personality is temporarily thrown aside to facilitate an action or set-piece dictated by the plot, the whole thing starts to fall apart in the mind of the viewer. These broad rules don’t just apply to storytelling. They’re relevant to the construction of any creative work.

Yes, gameplay is increasingly tied to game-world these days, and inconsistency in one will rapidly cause the other to collapse--see CLoS2’s illogical stealth sections, for example. But if the sheer nature of interaction, the essence of what a game is about, shifts around too much, the same is true in a purely mechanical sense. A disconnect just occurs in the player’s head, and everything starts to lose meaning. Is Lords of Shadow 2 a fighting game? A platformer? A stealth game? A puzzler? A shooter? It doesn’t seem to know, and so neither will the player.

Variety is good, but ultimately it needs to be built around a consistent, relatable hook, a core and set of values with which the player feels comfortable and at home. Without that, a game has no innate personality, and thus nothing with which the player can form a relationship. Just like with a person, if you can’t work out where a game is coming from or what it’s all about, it's desperately hard to relate to it. If all you see are disparate, schizophrenic traits without any solid, reliable grounding, it’s simply impossible to be friends.