What's the deal with exclusives? Let's put it in perspective.

What does "exclusive" even mean anymore?

When EA announced last week that it was bringing a former Xbox-exclusive online shooter to PlayStation platforms, Plants vs. Zombies: Garden Warfare probably wasn't most people's first choice. But even though Titanfall is solidly bolted to Xbox One, Xbox 360 (and, um, PC), Respawn Entertainment has given enough knowing winks to broader horizons for the franchise in the future that it's getting kind of lewd.

While we quietly save space on our PS4 hard drives for the sequel to the Xbox One's biggest shooter, how many awesome exclusive experiences should we expect to actually be exclusive? What does that term actually mean anymore, and why does anybody bother? We've broken down why exclusives seem to stay that way so infrequently in 2014.

What does it mean to be a console exclusive?

It means that game is only going to release on that platform. At least, that's what it's supposed to mean. But if you're the sort to pay attention to new releases, it may seem like every other game that was meant for one platform miraculously appears on the others within a year of its release. Pretty annoying for folks who specifically bought that console to play that game, right?

There's no perfect way to determine whether an exclusive will actually stay exclusive, but here are a few handy categories to keep in mind the next time you see a big shiny "Only For" logo.

Why make a game exclusive?

Most developers want their games to be played by as many people as possible. That means putting it on as many devices as possible. Platform exclusives by their nature limit the game's exposure--even if you pledge fealty to the most popular system, you're still cutting off the sizable potential user base of all the other platforms.

It's somewhat accurate to say that compromise is made for money. Lucrative licensing arrangements aren't the kind of thing that are broken out on a quarterly financial report, so they don't often make the headlines, but I feel confident saying EA didn't lock Titanfall to Xbox because Peter Moore and Phil Spencer are still BFFs. It's not just about healthy bonuses, though; developing for more platforms means higher costs. Reduced development prices and a healthy, guaranteed payment from your console partner can make a new project look like a much better wager.

Is it all about the money?

Well, not much more than everything else in business is about money. Shaking hands with a heavyweight console manufacturer means they're taking a vested interest in your game. It becomes a point of pride for the system, and it's marketed as such, with everything from a featured slot on the digital marketplace to special hardware bundles shipped to stores nationwide. That's a lot better than being another game on the shelf.

Relationships do influence the equation, whether or not Peter Moore and Phil Spencer still share a Netflix account. It's basic business sense: savvy folks are more likely to risk their time and money on people they know aren't going to screw them over. For example, even though Xbox 360 was much easier to develop for than PS3, Microsoft's still working to match Sony's momentum in recruiting indie developers for the new generation; Shahid Kamal Ahmad and Adam Boyes have been building indie PlayStation love for years.

What are first-party games?

Mario, Master Chief, and Nathan Drake are never* leaving their respective homes. The rights to their dangerous-but-never-permanently-fatal virtual lives are owned by their platform holders. If their mamas and papas leave, they still aren't going anywhere--though the business will have to find them a nanny, as was the case when Bungie bought itself back and left Halo to Microsoft's purpose-built 343 Industries.

*Ok, so I could have said the exact same thing about Sonic the Hedgehog fifteen years ago. There is a chance that these series will one day appear outside of their native systems, but not until some seriously dire stuff happens to the companies that own them--like going bankrupt and having all their stuff auctioned off or launching a Dreamcast.

What are second-party developers?

If HAL Laboratory says it's making a game, you can trust that it's working with Nintendo. Nintendo doesn't own HAL outright, though, so the studio is what's called a second-party developer. Microsoft may get tired of being irrelevant in Japan and offer HAL a Fuji-dwarfing mountain of yen to replace Rare in making Kinect games or whatever, and HAL could very well accept--given the studio can get out of any non-compete clauses with Nintendo. Until then, the houses of Kirby and Mario remain best friends--almost as good as Peter Moore and Phil Spencer, who may still wear matching salt and pepper shaker costumes to Halloween parties.

Square's partnership with Sony for Final Fantasies VII-XII represents the other side of this category. The company released several games for other platforms in that roughly nine-year period, but (aside from a PC port here or there) the main Final Fantasy franchise stayed loyal to Sony--one of its largest shareholders at the time. Once Final Fantasy XIII came around, business conditions had evidently shifted enough for Square Enix to lose the platform monogamy and ship on Xbox 360.

Why are specific franchises exclusive, even if the developer isn't?

These are the games that spawn a thousand forum posts about companies valuing cash over their devoted fanbases. Epic Games and Microsoft didn't have a particularly long history together before Gears of War--Epic was at that point largely a PC game maker, with a PS2 or Xbox game here or there. The two just happened to come up with a deal that worked well for Gears of War.

And it was just a deal--Microsoft didn't own all of the rights to Gears of War until it bought them from Epic in January. A similar deal likely kept Grand Theft Auto III, Vice City, and San Andreas first and foremost on PlayStation 2 even as the franchise exploded in popularity--though they did arrive on Xbox eventually. Like Final Fantasy, conditions evidently changed once Xbox 360 came around, because GTA IV and V hit PS3 and 360 simultaneously; like Peter Moore and Phil Spencer may still hit the batting cages after ducking out of work early on Fridays.

But, wait, how does exclusive DLC mix into this?

Why buy the cow when the DLC is free, right? Ok, so that metaphor made a lot more sense in my head, but perhaps the most common (and most annoying) form of console exclusive these days is the limited bonus. If video games were sold in late-night infomercials, these would fall into the "But wait, there's more!" segment rather than the initial pitch.

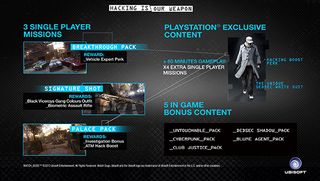

Call of Duty fans who want to get first dibs on DLC map packs have to buy the games on Xbox, as they have for the last few entries. Watch Dogs players who want to play through "60 minutes" worth of extra missions have to buy it on PlayStation, as Ubisoft has done for several Assassin's Creed titles. This lets platform holders say their players are the only ones getting the complete experience and it lets the game benefit from being a feather in a console's cap, if not the jewel in its crown. It also makes half your players feel like second-class citizens, as CD Projekt Red has noted.

Will it ever stop?

Platform exclusives have changed a lot in the last 20 years. As consoles become defined more by implementation than architecture, will exclusives become a thing of the past for all but the most established brands? Or do you think they'll become more essential than ever? Do Peter Moore and Phil Spencer still plan to buy a dilapidated tavern and refurnish it together? Be sure to let us know in the comments.

If you're looking to test out your new exclusive categorizing skills, be sure to check out our E3 2014 rumor round-up, or read our Top 7 amazing ideas hidden in mediocre games.

I got a BA in journalism from Central Michigan University - though the best education I received there was from CM Life, its student-run newspaper. Long before that, I started pursuing my degree in video games by bugging my older brother to let me play Zelda on the Super Nintendo. I've previously been a news intern for GameSpot, a news writer for CVG, and now I'm a staff writer here at GamesRadar.

The devs of a legendary indie Zelda-like have a new retro action game with "bumpslash" combat, and its Steam Next Fest demo is a gem: "Fans of Ys, take note!"

And you thought Hollow Knight: Silksong is late – 37 years in the making, this retro Metroidvania has a whip-smart Steam Next Fest demo that's as Castlevania as it gets

The devs of a legendary indie Zelda-like have a new retro action game with "bumpslash" combat, and its Steam Next Fest demo is a gem: "Fans of Ys, take note!"

And you thought Hollow Knight: Silksong is late – 37 years in the making, this retro Metroidvania has a whip-smart Steam Next Fest demo that's as Castlevania as it gets

Most Popular