Why did I sell my Xbox One? To play 20-year-old games obviously...

After deciding that I really wanted to play a bunch of ridiculously old games, there was only one choice: I had to sell my Xbox One. So I packaged it up along with my scant few games and pawned the whole beast off to the highest bidder, funding the purchase of a video processor whose sole purpose is to make 240p games look awesome on an HD TV. You know - like the Sega Saturn and the Neo Geo. The relevant machines in today’s gaming landscape, right?

I got rid of - what is for all intents and purposes - a thriving modern console so I could play old machines that haven’t seen a new release in decades. While that might seem absolutely insane to most people who consider themselves deeply invested in video games, there is a logic behind the decision. I have my heart set on finding the XRGB Mini Framemeister. Yes, that is the actual name of the video processor and not an old Simpsons joke about gaming consoles. It’s also a device offering greater opportunities to me as a player, as a critic, and as someone interested in how game design from the past 30 years has trickled into what we’re playing today. Games don’t stop being fun, fascinating, or relevant just because they didn’t come out in the past year. The problem is that playing games made before 2005 is an increasingly dicey proposition and not just because of the prohibitive cost of vintage hardware and games.

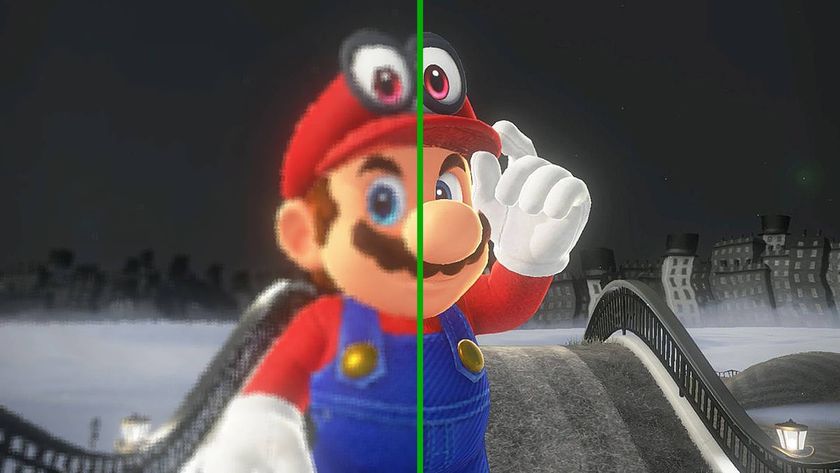

Consider the Super Nintendo, which has seen more significant releases in 2016 than Nintendo’s own Wii U thanks to the addition of its games to the Nintendo 3DS. Earthbound, Super Metroid, The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past; these are games that still define Nintendo’s identity. It’s great that these classics are available to people that may have never had a chance to play them (every device is someone’s first, dear gamers), but the preserved experience isn’t necessarily precise. Even when an emulator is excellent, like the one running A Link to the Past on 3DS, it’s not exact. The graphics alone lose something in the translation process since the pixel art was itself designed to run on a device that only outputs in 240p on a 4:3 television. For anyone that goes to play that game on Wii U or Wii through Virtual Console, they’ll find a game that loses even more of the clarity and detail due to some particularly dim emulation.

But playing those games on the original hardware plugged into an HDTV, which you can easily do, isn’t the solution either. The image is stretched out and warped as a modern television’s video processor tries to convert the 240p signal, resulting in something that isn’t as fun to watch AND doesn’t play right, thanks to an input delay. In the absence of a super fancy and super heavy CRT television the XRGB Mini Framemeister will get your retro consoles, from the NES to the original Xbox, looking and playing 99.9% right on an HDTV. If you’re curious about the nitty gritty of how this works, NeoGAF’s IrishNinja wrote an absolutely wonderful breakdown a few years back that’s still essential reading for anyone that wants to get old games running properly on modern monitors and TVs. The end result is a game that looks absolutely stunning. Jumping from a Super Nintendo plugged straight into a Sharp Aquos LED to a Super Nintendo run through the XRGB Mini is like jumping from a VHS copy of The Hateful Eight to the 70mm roadshow version of the movie. The difference doesn’t seem like it’s going to be dramatic until you’re playing the game yourself.

But if that’s the how, you might still be wondering why? Why go through all the trouble, even going so far as to get rid of a console people are still actively developing for, to get something like A Link to the Past running correctly? In the case of Nintendo, A Link to the Past is arguably at its most significant since it first came out. Right now Nintendo’s identity is in flux. The company is shifting its developers to making mobile games, the NX is going to dissolve distinctions between its home and portable consoles, and a brand new Zelda is going to be the lynchpin game to usher in the transition. Going back and seeing A Link to the Past in its original shape and form is deeply informative for anyone that wants to dissect where Nintendo is going today, and for finding out what in these storied games is worth preserving or casting aside in modern game making.

It’s not about nostalgia. It’s about context. The XRGB Mini doesn’t just shed a piercing light on Nintendo either. With Street Fighter 5 proving divisive for fighting game fans, it’s been brilliant diving back into Capcom’s experimental work from its fighting heyday. What better way to assess what the company’s fighters are in 2016 than to pick up pixel-perfect versions of X-Men vs. Street Fighter or Vampire Savior? Rather than closing studios and shoveling out crappy Sonic games, Sega’s been doubling down on preserving its history, republishing games like Valkyria Chronicles and making a huge library of its Genesis games officially available to modders on Steam. If people are making versions of Streets of Rage 2 where enemies make the Tim Allen Home Improvement noise, then it’s high time to go back and play the original Genesis version as it was built to be played.

So I sold my Xbox One and used every penny from the sale to buy a device that, at first blush, looks like little more than an absurd gadget for people that can’t let go of the past. What the XRGB Mini helps facilitate, and what it’s helped me experience first hand, is that the work of generations past doesn’t just inform what’s being made today in a distant and abstract way. Old games live and breathe, provided you can find a way to play them, and it was well worth altering the landscape of consoles in my home to make sure I could do so. If you find yourself wishing the console in your basement or attic was hooked up in your living room and running as well as an Xbox One, PS4, Wii U, or even PC gathering dust, you’re not crazy. And you have options.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Nintendo Switch 2 Direct reveals Hyrule Warriors: Age of Imprisonment, a Legend of Zelda spin-off set before Tears of the Kingdom

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom are getting enhanced Nintendo Switch 2 Edition releases, with improved frame rate, resolution, and more