Why comic books became a more of a writer's and less of an artist's medium

Money's the main reason comic book editorial departments are filled with word-people and not picture-people says one prominent pro

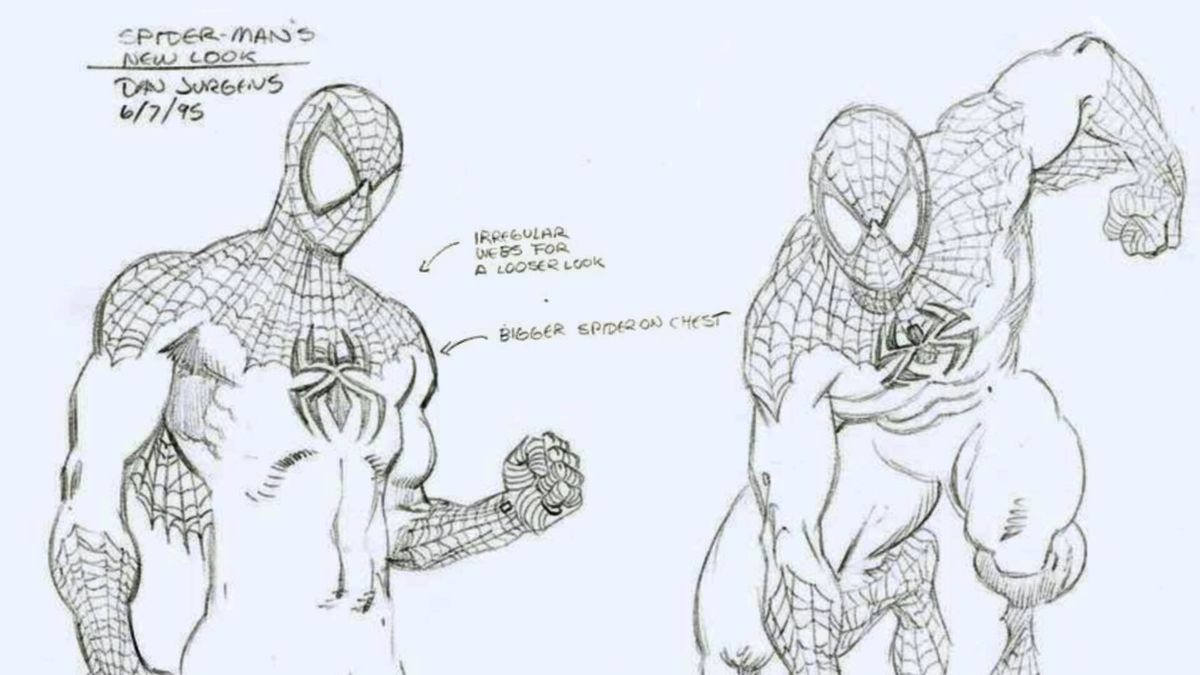

Picture this: It's 1995, and you are Dan Jurgens. You've been a top-flight comic writer and artist for a dozen years, and having been part of the groundbreaking Death of Superman, you're as household a name as it gets in comics.

But there's a motherlode vein of old-school fanboy in you, and just after you send in your first pages for a brand-new Sensational Spider-Man book at Marvel, the phone rings. Your heart rate ticks up a tad because on the other end is comic book royalty—John Romita Sr., the longtime Spider-Man artist, now Marvel's art director.

"John Sr. called me up and said, ‘Now I just want to have a conversation with you, that's all,'" Jurgens recalls. "He was so nice and polite and helpful. He said, ‘Your Spider-Man is a little on the bulky side.' He might even have used the word ‘weighty.'"

A FedEx package was already en route to Jurgens, and when it arrived later that day, "It had several sheets of tracing paper where he had gone over my figures and did his John Romita Sr. take," Jurgens says. "And I could immediately see he was absolutely right. I had come off seven-eight years of drawing Superman, and now looking at my Spidey…yeah, I needed to make some adjustments."

Jurgens got it, because Romita got it. Jurgens quickly made some changes, and everything was right as rain. Problem solved.

The problem today? Both that kind of contact, and that kind of solution to a problem many wouldn't even recognize exists, are gone. Because by and large, both art directors and even editors with artistic chops are gone from the comics landscape.

Make no mistake: Whereas comics is story plus art, in 2022, "story" primarily means the writer's story.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"The way this industry works, typically the writer has that bigger role in shaping the storyline and direction of the book," Jurgens says. "That's not to take anything away from the artist; and clearly I've worn both hats, sometimes at the same time. But mostly it's the writer in that role."

The main reason is man-hours required. It's often said it takes a writer 12 seconds to type "A thousand soldiers come rushing over the hill" and it takes an artist 12 hours—likely more!—to draw it. And in today's world of pixel-perfect reproduction and fan demands for enhanced realism, artists cannot keep up with a writer's pace.

"In a two-year run on a book, a writer is going to be there every single issue," Jurgens says. "In this day and age, artistically, that is incredibly rare."

That's reality, one way or the other. But there's also a choice companies such as Marvel and DC have made, which is to eliminate art directors, and at the same time, editors are skewing more and more toward words rather than pictures. It's creating a brain drain. The pictures may be prettier and more spot-on real than ever, but are they telling the story?

"I think maybe 20 percent of artists in comics today really get storytelling," says Mark Waid, a longtime writer and editor, currently also the publisher at Humanoids. Waid is sympathetic to the plight, both from the artist's and the editor's point of view.

"There's really not any time from an editorial standpoint with the grind, to teach artists storytelling," he says. "They don't have time to teach a guy how to tell a story like Alex Toth, Chris Samnee, or Howard Chaykin. I think we're past the point of being able to teach people that. The best they can hope for is that the arm looks right."

Howard Chaykin, a now 50-year vet as both a writer and artist, is doing his best to stem the tide. He's taught his 'Paradigm' courses live and in-person to Marvel and DC editors, and hey—anyone can check it out for free online. He sees willing faces in his crowds, but just not enough who can grok what he's dealing out.

"The editorial staffs at the majors are staffed almost entirely by writers, who have little or no narrative sensibility, who know little of what a narrative picture means in the context of a page or a panel," Chaykin says.

A main symptom of that disease is that, by and large and rightly or wrongly, comics today is frequently seen as a writers' medium, with the artist subservient to the writer's vision. Chaykin believes this to be the case (and let's give him some room to roam):

"I do," he says. "For a number of reasons. One, the artists have allowed the situation to evolve in this way. They have allowed the writer to become the alpha. Two, the reading of the general public and comic hobbyists—which is where most comic writers come from—is diminished. My cohort came in with a broad, liberal arts education, which included the classics whether you liked it or not. We read the Western canon. We widely read fiction, we saw every movie. We had no relativist idea. The new generation—and by that I mean anyone between the ages of 20 and 60—has been reading YA fiction for entertainment, and they are satisfied by this. What I mean by that is what they're demanding of writing is serviced by purple and melodrama."

"Three, since comics have evolved more into an ancillary product of IP, the powers that be—the management class, the movie-and-TV people—cannot identify what writing is in comics. They perceive the writer's job as writing, and the artist's job as illustrators. But comic book artists are—or at least should be—graphic designers in the service of narrative, pictures of narrative value, which means ‘story value.' The way an artist sets up a picture is the writing of the book. The writer provides a template. And certainly in this delusional Marvel-style thing where a writer says, ‘Give me a fight for five pages,' who's the writer on that? And since comic book fight scenes are external reflections of inner trauma, they are the equivalent of dance numbers or aria in ballet, opera, and musical theater, and choreography is storytelling. You see my point.

"But for the most part, these people can identify the skill sets of artists at most in a shamanistic sense. It's transubstantiation. But they know what a writer can do. They have a keyboard, they have a monitor, they know what that work is. But they cannot begin to imagine what it is that the artist is doing to the writing to make the writing actually writing on the comic book page.

"Fourth and most significantly, the major comic book companies have invested a tremendous amount of time and effort in diminishing the significance of the artist in the name of the writer because artists are perceived as rebellious, freebooters. And no one on the business end of the comic business ever wants to see anything like Image and what these artists did in the early '90s again. Writers are not perceived as being the type to do something like that. But look at this Substack deal. It's Image Comics all over again, but now it's writers. But they are doing it in a more professional manner, not doing easy pastiche of what made them popular in the first place, because they are not self-identified rebels. They're not ‘putting one over on the man.'"

Chaykin's points should be well-taken, and food for thought if not action items for anyone with a concern. But there is the question of 'rightly or wrongly,' and let's face facts, it's hard to stem the tide. But right-thinking comic editors are on that wall.

"A writer without an artist is just writing prose," says Rob Levin, executive editor at Valiant Comics. "I object to when people credit comics as ‘writer's name with artist.' That somehow implies you could have a comic without art, and I hate that. Comics can't exist without having art. It's kind of how the medium works."

But Levin admits "that is sort of the way this industry is structured," today, and calls on writers to do their part as well.

"I don't know that there are enough writers who truly think through the visuals to get to a point where they're not creating problems for the artist," he says.

Alas, there are hurdles to overcome, including history, language, and the chicken/egg problem of who gets paid, and how much. Tom Brevoort, senior vice president and executive editor at Marvel addresses the history.

"It's always kind of been true," Brevoort says. "Even at DC, there was a split in responsibility between the writing and the art. We think of the editor as kind of doing everything, but Julie Schwartz was kind of workshopping the writing, and he had some say over who was doing the art, but those assignments were really handled by Sol Harrison and so on."

A massive change—for the good—happened at DC in 1966, when artist Carmine Infantino became the company's editorial director, and later publisher. Infantino brought in top artists such as Joe Kubert, Joe Orlando, Dick Giordano and more as editors. By the late '70s, Marvel was hiring artists such as Carl Potts and Larry Hama as editors. An editorial synthesis of writer and artists existed, and gave rise to new writer-artists such as Dan Jurgens and more.

Alas, things started to drift. Brevoort, who studied illustration at University of Delaware, is trying to get some of it back.

"We do a reading circle with the younger editors every week," he says. "We read, dissect, and discuss both current and older books. And when I say ‘older,' I don't mean ancient, it's 2006 or whatever, and it's amazing to see how many reactions are, 'This stuff is heavy. It's slow. It doesn't pace the way I want it to. There are too many words. The balance is off.' There's a weakness there of a skill set. A lot of editors today don't have the artistic training, or maybe even the language to discuss some of this stuff effectively with their artists."

Mark Waid alluded to 'the grind' earlier, but the real elephant in the room is always money.

"The paradigm changed, my friend, in 1980 when companies started paying royalties," Waid says. "Back in the day, Dick Giordano would freelance on the side, but make his really good money as an editor at DC, more than he ever could at home inking Neal Adams. That changed when royalties came in. Everyone in comics is underpaid, but editors are so underpaid. You'd have to be an idiot to be an artist and say, 'Y'know, I'm gonna give this up for a $50,000-a-year job in New York City.' That's the main reason we've filled editorial with all word-people and not picture-people. Picture people can make better money drawing pictures."

And the tug between words and pictures—alas, history again—can be extreme.

"The problem is we keep swinging the pendulum so far back and forth," Waid says. "For the first 30 or 40 years, yeah, comics was very much a writers' medium. Then Carmine Infantino comes in as editorial director in the mid-'60s and suddenly it becomes better. Then the thing that really puts it over the top is when the Image guys say, ‘No, no, it's absolutely an artists' medium.' Comics in the '90s and early-aughts was all art-driven. Story and words on the page were completely secondary."

Waid thinks—and Chaykin largely agrees—that today's status quo is a whipsaw back against the formation of Image Comics.

"Now because of Grant Morrison, Brian Bendis, and people like that, it's pulled back to what looks like a writers' medium," Waid says. "What that does, I fear, is it sometimes makes the artists, very creative people, feel less invested in the story. And if they feel less invested, there's less of them in the story. It becomes, de facto, more a writers' medium."

It's certainly not all doom and gloom, and the tide may be changing, with more artists sitting in editorial seats.

"We have three editors at Valiant, including myself," Rob Levin says. "Our assistant editor, Audrey Meeker, is a recent graduate of [Savannah College of Art and Design]; she's an artist. DC has a number of similar people. Marquis Draper is a SCAD graduate. Amedeo Turturro and Paul Kaminski both went to the School of Visual Arts. Marie Javins, the editor-in-chief, was a colorist for 20 years. So there is definitely art background. But there definitely are a lot of English majors, film majors, ‘people who can't draw,' and I count myself in that category."

No one really wants to admit to a 'brain drain' in comics. Most chose their own term.

"Skill drain might be better," Dan Jurgens says. And Jurgens himself stands in that gap, albeit unofficially.

"A few years ago, I was in DC's office," he says, "and an editor held up a page and gave it to me and said, ‘There's something wrong here. I don't know what it is, but I can tell there's something wrong.' And I did the John Romita thing. I took some tracing paper, slapped it down, grabbed a pencil, and zsssh zsssh zsssh, started drawing over it. ‘Your perspective's wrong over here, your composition is messed up here,' and boom. Fixed. And I think that's what's missing now. Once upon a time, there were editors who could do that. Now, not as much. It's a skill drain. That person is no longer on staff.

"One of the two or three biggest changes I've seen since I started in comics is that the people who started me had that base of knowledge because they had done it," Jurgens concludes. "They had that background. And that's what we have lost."

—Similar articles of this ilk are archived on a crummy-looking blog. You can also follow @McLauchlin on Twitter