Who really was Stan 'The Man' Lee? A biographer tries to find out

Uncovering the man, Stan Lee, inside Stan 'The Man' Lee

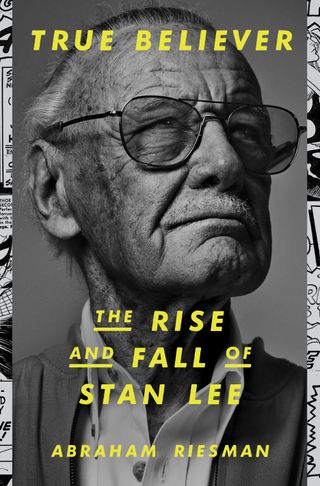

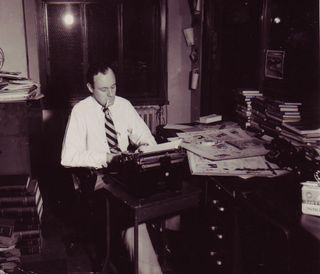

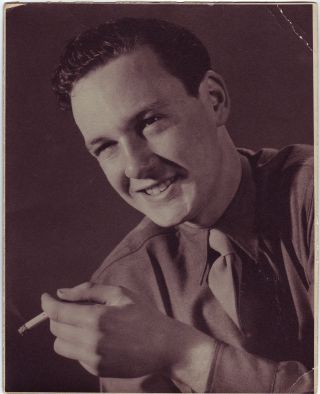

True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee is billed as "The Definitive Biography" of the real person who's seen by many as the driving creative force behind Marvel Comics. Beyond the 'Stan's Soapbox' editorials, the countless film cameos, and the face seen at comic conventions, this new book gets into the real details of the man born Stanley Lieber; from the earliest days of his childhood to his painful final years…and of course, the birth of the Marvel Universe in between.

True Believer has already earned both controversy and acclaim for its warts-and-all portrait of Lee. While not a Mommie Dearest-type hack job, it doesn't shy away from how Lee built his own mythology, often at the expense of his collaborators; from the many failed attempts to break into areas of entertainment outside of comic books, to the scandal-filled problems of Stan Lee Media in later '90s and early '00s, to the disturbing reports from his final years of elder abuse and his complicated relationship with his daughter J.C.

For a man whose public face was a larger-than-life figure, True Believer shows the real struggles behind that image; not so much dismantling Lee's legacy as presenting it in a new context that suggests that in some ways, his real achievements in comics were overlooked even by Lee himself.

The book's author is Abraham Riesman, who's previously introduced many complex aspects of comics history to a wider mainstream audience with his in-depth pieces for New York magazine, including a 2016 piece on Lee that spun off into this book. Riesman's research included numerous interviews and access to rare materials from Lee's archives that few fans have ever read.

Reisman spoke at-length with Newsarama in the days leading up to the book's February 16 release for a long talk about True Believer, the complexities of comic books and their creation, and the realities of "Stan, comma, the man."

Newsarama: So, Abraham, the book's gotten some great blurbs, and gotten some very… impassioned… responses from people who haven't read it. What feedback has meant the most to you so far?

Abraham Riesman: Well, I was very flattered Neil Gaiman blurbed it. That was the biggest, most pleasant surprise in a lot of ways! He's a busy man, has a lot going on, and we sent it to his people as kind of a 'Hail Mary.' Two days later, he emailed me back with the subject line, "You Bastard," to let me know he'd blown a deadline because he was so preoccupied reading my book.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

The most common response I've seen in the Facebook page I've set up for the book is, "What fall? He never fell!" And I keep saying, "Read the book, and you'll find out what I mean!" And I should probably give them more information, because they keep going, "Classic clickbait journalism! Trying to get me to buy the book!"

Nrama: Like those old Time Life Mysteries of the Unknown commercials. "Read the Book!"

Riesman: Oh my god, I remember those.

But the good news is, I haven't gotten into any flamewars yet. The people who hate the book…haven't really read it, and I'm past the point where I get into fights online. To play is to lose when you have a flamewar. But those are the two poles, very positive and not-so-positive.

Nrama: But you do tap into what's controversial about the book, because I think there's still some resistance to the idea of 'idols have feet of clay.'

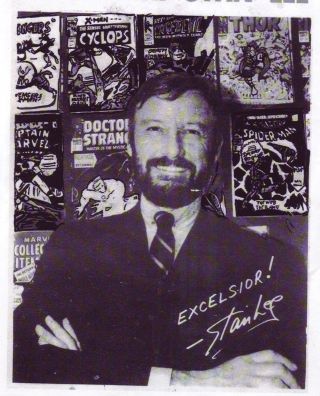

Riesman: Look, there's a wide swath of the American and worldwide public that has fond feelings for Stan Lee. For many, many people in his life, whether they were main characters or people he met just for a moment at a con, he was very, very friendly, very, very supportive. And that's how many people I talked to saw him.

But the more digging you do, the more you learn he was… a guy. He was a person, he was a human being. He had some qualities that people might think of as great flaws. And it's hard to reconcile the fact that you can love someone, but they've done things that you're not super-proud of.

Lately, I've been doing research into my grandfather, who was a major figure in the Jewish world in the part of Rhode Island where I live, and I love my grandfather, I was very close to him. Once I started doing this research, I found he had a lot of political views that I didn't agree with! He was very outspoken about a lot of things that I'd be outspoken in the exact opposite way.

But he's still my grandfather. If you were to bad-mouth him, it'd be very hard for me to hear that. Does that mean my grandfather doesn't deserve criticism, or that I shouldn't listen to the criticism? No. It just means that it would be very difficult for me, and I understand where people are coming from.

I quote someone in the introduction who was outside this Stan Lee tribute event in Los Angeles, and he said to me, "Stan Lee was like a father figure to me. I didn't have a father growing up, and Stan was this fatherly influence on me." That's not an uncommon sentiment. There were a lot of people for whom that was true, or was supporting these things they loved while also generating these things they loved.

Whether he was the Soapbox figure, or the host of the Marvel cartoons, or those cameos in the films, he's always been portrayed as the guy who's responsible for the thing you love, you know? And that's a very intimate bond between the consumer of art and the creator of art, that idea that the thing you love has a parent – if not the parent of you, then of the thing you adore.

The fact is, he did a lot of stuff that people would find less than savory, and I didn't come to this book with an agenda. I have nothing against Stan. But at the same time, I don't have special affection for Stan Lee. I had to get into the mindset of the 12-year-old geek in myself and say, 'This is a person, where I have a job to do, which is to understand him, and to explain him.'

That's my long-winded way of saying, I understand why people might be reluctant to engage with this kind of narrative. I hope people give it a chance, I hope they don't Gamergate me, but I understand where they're coming from.

Nrama: Well, two things come to mind there. First, there's the quote you have from Gerry Conway in the book describing Stan as, "A good guy, but not a great guy." And that stayed with me, because it's the larger-than-life aspects vs. the flaws.

The second thing is that quote from Julius Caesar, "I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him—"

Riesman: Yeah! I am here to bury Stan, or to at least exhume his legacy and examine it. I know there have been a lot of writers who've written about Stan, be they journalists, be they historians, be the cultural theorists, whoever, and they have come to praise Stan and that's fine.

I have nothing against that, that's their prerogative. There are a lot of people who wanted to approach Stan's work from a place of enthusiasm and positive analysis, that's fine. I just don't think that has any place in a biography.

I'm not saying you have to be overly negative in a biography either, but we shouldn't be aspiring to trying to convince people that these things are good – you know that this art is good, or this person was good. That is not something that we should be trying to convey in a biography. We should be trying to convey to the best of our ability what happened, not evaluating it as good or evil, to the best of our ability.

Now sometimes you have to sort of label a thing, or at least you present things that are relatively unambiguously bad as being bad. But that does not mean you should err on that side.

Nrama: Well, you're looking at it as and forgive me the pun, but it's "Stan, comma, the man" that you're looking at.

Riesman: Exactly! It's "Stan comma, the man," and that was what I was that's what I was paid to do and that's what I wanted to do, and I hope people think that I was able to pull it off.

Nrama: Again, when you're looking at this particular story you know what's kind of the conclusion you came to about it? Because on the one hand, your book is very much about deconstructing Lee's self-allegations and the self-built myth, but on the other hand, there is evidence that he was, through his tenacity, through his moment of great inspiration, able to tie a number of terrific talents together to create these things. He may have gotten a lot of credit over them, but he still helped bring together all these things.

So, what do you ultimately view as Stan Lee's accomplishment, as a creative or editorial or persona or…?

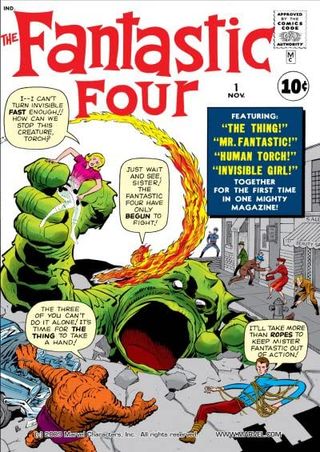

Riesman: His biggest accomplishment, far and away, is the concept of the interwoven shared superhero universe. That is something that we can pretty unambiguously credit him with, because all of the big ideas from back then were largely Stan, or Jack Kirby, probably maybe more one or the other, maybe a lot more one or a lot more than the other, but the point is, in this case Jack not only never claimed credit for having come up with the idea of the shared universe, but actively – according at least to his assistant and eventual biographer Mark Evanier – Jack hated the shared universe thing because he wasn't doing all the books.

So, that meant when he was writing these stories – as you know from doing this interview, he was the primary writer on them – Jack often had to deal with other people's stories that he hadn't written and incorporate continuity from them. And that irritated him, according to Mark.

But, Stan, therefore, by process of elimination, is probably the person who came up with the idea of the shared universe. And that's a massively consequential creation – not just from a business perspective because my God, what a genius way to sell a product in narrative form!

You're telling the little kids that the only way they can totally understand what happens in a given story is by reading every story! It's genius! I don't know why nobody had thought of it sooner.

Nrama: It definitely messed with my head as a kid. In the pre-Internet days, I'd spend my money on trading cards and The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe just to catch up.

Riesman: Me too! Me too! I've got a line in the book and I'll say it again here: Roger Ebert, the guy who inspired me to write about the arts, used to say that the movies are like a machine designed to create empathy, and superhero comic books, thanks to Stan, or at least especially thanks to Stan, are machines designed to create addiction.

You know, the idea behind superhero storytelling is, 'How do we hook you and how do we keep you?' And it's something whether you think that's moral, immoral, good, bad, whatever, you have to acknowledge that nobody had really done that in that form.

And that's something, even if it was kind of accidental or Stan backed into it. The fact that he committed to it and made it relatively coherent – I mean, obviously there were No-Prizes, because he didn't always get it right. But you could think of it as a unified world.

And here's the thing: On the one hand, it's a machine designed to create addiction, and that's some people may find that distasteful to think about. But, on the positive end, there's a tremendous opportunity in that kind of storytelling. Having these massive tapestries of stories that you can never almost assuredly never actually read all of is this fascinating immersive experience. You're always confused, there's always something you don't get. And no matter how many additional comics you read, it's Whack-A-Mole.

Now, that's kind of Sisyphean, right? Like rolling that boulder up the hill, hoping we'll understand all the comics, and it never happens. But that agony of not being able to know everything is, I think, a special kind of artistic experience. And on top of that, you can tell these stories that are so iterative because it's all part of the same story with the same characters, you can have creators be the artists.

Writers, regular artists, whatever, they're able to pick up the toys left by a previous generation and completely reinvent them or continue them or slightly tweak them, or whatever, comment on them with other things.

And you can't do that in any other medium. Any other medium-genre combo, I should say. You have long-running stories like soap operas, but those are not interconnected with one another at a fundamental base level.

Superhero comics are, in the Marvel Universe – and the DC Universe, which ran all along behind in order to catch up – have become these stories of massive proportions. They're hyper-objects, where you can actually hold in your head every single chapter of the Marvel story.

The story of Marvel Universe is so immense that no one person – well, there's Douglas Wolk, who tried to read every Marvel comic, but the idea of him getting that contract was, 'What kind of crazy person would try to do that?' And the fact is, nobody, other than him, probably has ever done that. And you end up with this special kind of storytelling that can't be created elsewhere, and that will never be fully complete in your head, that the thrill of experiencing it is so overwhelming that you just can't get enough.

Nrama: Abraham, one thing that's also really interesting about the book is the recurring concepts you see of nepotism and business, and the concepts of overreaching – you know, if you want to get into the classic elements of tragedy.

What do you think are some of the precedents that Stan established regarding his sense of business and self-promotion, particularly given the movement towards creator rights and credit in more recent years? Certainly, there was even less credit given to the different people who worked on comics when he started in the industry, but there is a massive difference between the world he entered and the world he left.

Riesman: Here's the thing – Stan gets a lot of credit for the credits. He wasn't the first person to credit artists and anchors and letters, DC had done that sometimes. But he was certainly the first person to do it in superhero comics with, at least, the kind of at the scale he did, with just virtually every issue delineating that stuff. That's admirable. We should be happy about that.

One thing where I'm okay not being neutral when it comes to my reporting on the comics industry is when it comes to creator rights, at least as an overall idea. I just think other journalists may have completely different assessments, and I'll respect that. But for me, I feel like the fundamental injustice of labor writ, labor relations in the comic book industry is something that I just feel very passionately about and I'm not afraid to – in a way that's not overbearing, because the books not about me – sort of put in my thoughts about that.

So, the credits are something that we should be glad about, because people should get credit for their work. But at the same time, overall, I would say the ledger is very much in the red for Stan when it comes to creator rights.

I mean, this was a guy who did not invent the concept of work-for-hire, he's not Martin Goodman. Goodman started this exploitative machine – his company went by so many names I usually just call it 'Goodman's Company' – and Stan was just, initially, a gear in it. But he really became a full company man who internalized the idea that this was how breaks work and perpetuated this unbelievably unjust system where creators don't have any control of ownership of or remuneration for the use of their characters.

The point is he helped perpetuate, more than almost anybody who didn't start a company, this unjust system. talked a lot about credit. And when I say "credit" in this case, I mean like who was credited with creating the Marvel Universe characters. But one thing that I think often gets obscured there is people will go, 'Well, okay. We don't know we weren't in the room, maybe Stan was responsible for the initial ideas and deserves that credit, maybe Jack is responsible. Let's split the difference, we'll just say they're both co-creators and that's the credit that we'll get.' Okay, fine. I disagree with that methodology, but fair enough.

The trouble is you can't reasonably argue that guys like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Wally Wood, Don Heck – you know these people were not getting paid for writing comics that they were writing. That's not about going like, 'Oh, let's split the difference and say this person was co-creating X with this other person.' This is something very rooted in cold hard cash and the basic principle of fair capitalism, which is if you work, then you're properly remunerated for your labor.

The 'Marvel Method' meant the artists were writer-artists who were not just regular artists, but the primary writers on these comics. The conversations that you hear about, the story conferences where it's Stan and the artists talking about the stories are going to be, and Stan's jumping up on the desk and acting stuff out…um.

For one thing, Jack Kirby always said that was not how it worked with him – he would just tell Stan what he was going to do, and then he went and did it. Even if Stan is contributing ideas here, according to Stan's own descriptions, very often, he was just saying, "Okay, let's have Dr. Doom come back, and the FF fight him."

That's an editor. That's not a writer. [laughs]

At that stage, you're not writing anything. You're saying, 'Hey, writer, go write this story that has the five or six elements I'm tossing out in this casual conversation.'

The writer-artists would then go home and write the story. They're writing it visually, but that's writing. There was no story prior to the writer-artist sitting down and actually doing it. There were just keywords, or maybe a vague narrative outline as best as we can tell, because Stan wasn't writing scripts. He wasn't writing down treatments. He was having these brief conversations, the nature of which we don't know. And then, even if he was contributing a lot of ideas, at the end of the day he's not the person writing the comic. The writer of the comic is the writer-artist, and then Stan ends up doing the embellishing at the end.

Now, the embellishing is really important, because the use of language is Marvel Comics is something that really transformed the genre in the media. So, the narration and the dialogue are really important, and that's why Stan is still a writer on these things, he's just not the primary writer.

For God's sake, the artists would very often, when they were doing the 'Marvel Method' stories leave little notes in the margins about dialogue and what's going on. Even if that dialogue doesn't get used, the fact is they are, again, doing more than just contributing. They're the people coming up with the structure of the whole goddamn thing, and then Stan, as he would put it, gets the stuff back and basically, like a crossword puzzle, he'll sit down and try and fill in words, where just structure has already been set up.

So, I'm not saying he's not a writer. I'm saying he wasn't the primary writer. And the fact is, these artists were not getting paid as writers, and that's bullshit, that should not have happened. That was a bad system. And the trouble is, a lot of that system – obviously, the 'Marvel Method' isn't used that much anymore, but a lot of that on the other injustices there are still around, whether it's work-for-hire – meaning you don't have any ownership over your creations, which also is bullshit, and something we just accept even though we shouldn't – and then there's the boys' club mentality.

Not that Stan was like a lewd weirdo who would derive any kind of… I don't have any evidence of him sexually harassing anybody, per se. But he later would try to make himself out as this champion of women – he wrote passages for the book The Superhero Women in the 1970s – he was always eager to take credit for being a progressive icon, even though he never really put that much effort into doing that.

The fact is, there's a lot that's baked into comics that came out of this era that Stan was responsible for, and that isn't great. And it's mostly in the area of labor relations, I think. But that's something that we really shouldn't be happy with, or at least shouldn't just sort of accept as 'Oh well, that's how it happened.'

Nrama: I think there's really a tendency to mythologize, and you talk about this in the book -- I'll just call it 'The Aaron Sorkin Figure' because he's always doings scripts like The Social Network or Steve Jobs things where there's usually the great genius who is guiding everything to these big achievements. There's that line in Steve Jobs, "Musicians play their instruments. I play the orchestra."

And that is an achievement, but…you still need a good orchestra! You can be the greatest conductor in the world and it's not going to mean anything if you have people who can't play their instruments or keep up with you.

Riesman: Yeah. And the writer-artist in the quote unquote 'Bullpen,' although it wasn't really a bullpen by that point - those are the people who were the team. They were the players, and yes, Stan was a really good coach, he was a really good editor.

I mean, he knew how to pair people up well. He was amazing as a non-artist art director – he had such an instinct for covers, what they should look like, how they can grab people, he was great at writing copy. That kind of editorial work he was really great at.

But he never wanted to be known as the greatest editor in comics. If he'd been known as that, he'd be Julius Schwartz… who is a figure with a lot more problems. But Julius Schwartz is still remembered, even though he's got issues these days, he's remembered fondly by a lot of people in comics. Who knows about Julius Schwartz outside of comics fandom? Basically no one, and Stan didn't want to end up like that.

So, Stan never talked about being the greatest editor. He was always the ideas man, and he's the writer. And the fact is, we have no idea if he was actually the ideas man; we have no clue whether he came up with those characters. As I say in the book, there is zero evidence that Stan Lee created those characters that he was credited with creating.

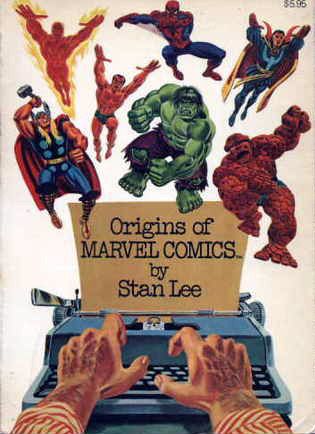

Now, there's also zero evidence against that. All we have is Stan's word. Stan always said that was who he was, that was the whole song and dance, but there's no evidence of it. There are no presentation boards, diary entries, there's no pitch. There's that synopsis of Fantastic Four #1 that could have been written by anybody. And Jack always swore that it was done years later as some kind of forgery. Even if it wasn't a forgery, Stan said in the Origins of Marvel Comics book that he wrote the synopsis after he'd already discussed the comic with Jack and Mark Goodman.

There's no evidence of him being the creator of the Marvel Comics characters, but that's what he wanted to be known for. He wanted to be known as a great writer. And there, once again, I have to be the person who lets everybody down by saying he wasn't the main writer.

Nrama: There's some evidence of him… trying to be the "ideas man" in different accounts. I was just reading the book Previously on X-Men, about the production of the '90s Fox cartoon X-Men, and the people involved talked about how Stan inserted himself in the project, tried to go with the '60s X-Men, went over their heads to the network executives, and they tried to minimize things because some of them had worked with him on the 'Pryde of the X-Men' pilot and let him do what he wanted and it went…badly.

Riesman: Yeah, that's a good example, 'Pryde of the X-Men' is a bad cartoon. Good theme song, though.

Nrama: Which he claimed to have written as well.

Riesman: Here's the troubling thing about looking at Stan Lee's career: You have basically, 1961 to 1971 he's making comics that change the world, or at least he's participating in making comics that changed the world. Before that, and after that…nothing. There was nothing that moved the needle in any appreciable way culturally.

And the thing that's hard to accept is, that's not because he was an unsung genius. Even he would tell you, prior to the Marvel Revolution, he was just a hack churning out garbage. And you can argue about some of the merits of some of it, but he wasn't proud of it, and it doesn't really have any staying power.

The trouble is, oftentimes people will tell that story like, 'Oh he was toiling away in obscurity and just churning out nonsense, and then he had this moment on the road to Damascus where the scales fell from his eyes and he realized he needed to make good comics and then he just started making good comics.'

The trouble with that narrative is not so much that it's implausible – although it is implausible, he contradicted himself a lot of times on the story of how that all happened – the bigger issue is, you got to look at the stuff that happened after that. No one ever looks at the Stan Lee products that came out from 1971 to his death in 2018. You know, that's a huge stretch of time. That's a crazy long period of time in a man's life!

And it's not that he wasn't creating, you know, he was still coming out with stuff. Now, a lot of it never saw the light of day, at least from the '70s and the '80s and into the '90s, because a lot of that work was him pitching things – doing treatments for movies or kids' books or TV shows or whatever, that stuff the average person has never seen. You have to go to the archives or talk to old contacts to find out where it is.

And if I may editorialize for a moment – it's not very good. When you look at his scripts – he actually hardly ever read scripts but you look at his treatments and pitches for these things, I defy anyone to read them and say, "This is an inspired idea."

And that didn't stop him – he kept going. You've got Stan Lee Media, you've got POW! Entertainment, these companies that never produced anything that caught on. You know, the closest thing to something catching on for Stan after 1971 – 1971! – is Stripperella in 2003, which became a national joke, and therefore at least something people were paying attention to. You grab the average person on the street, they can't tell you one thing he did after 1971, maybe Stripperella and that's about it.

But he produced this dizzying array of stuff, whether it was pitches and treatments or later with Stan Lee Media, and whether it was finished products or announcements for finished products that sometimes didn't actually see the light of day, all this stuff was happening that he was involved to one degree or another. Sometimes it was just him slapping his name on it, but usually he actually – from what I understand – he really did actually pay attention and say, "I want to put my name on this or not." He was really doing that much creative work.

Nrama: It does seem like once in a blue moon, he had some ideas that were ahead of their time – you talk about his idea of doing Sentai for America, which later came to pass without him as Power Rangers, or his lifelong obsession with trying to put wacky captions on photos – look at what we see now with memes today.

Riesman: That's a fair point! I didn't consider that. But you pick up a copy of You Don't Say! or the others…

Nrama: I didn't say they were good.

Riesman: Yeah, I mean, these are not books that caught on, these are not projects that caught on. And yes, occasionally he had some good instincts. He did have the right instinct that superhero movies would take off someday, but then again, he wasn't the only person who thought that. And when he thought that, I'm not sure, I can't read his mind, but when it came to pushing superhero movies, I don't know that was a case of him going, "I really believe in this genre."

He could just as likely have been saying, "This is the genre I accidentally fell into, and I might as well try and make it," because when he had the opportunity, he never pitched comics, and he hardly ever pitched actual superhero stories… for a while. Then, once he was at Stan Lee Media and how he kind of didn't have a choice, he did superhero stories, but I'm going off on a tangent.

Nrama: I know nothing about that, so I'm judging you very hard.

Riesman: What I'm saying, no one paid attention to that shit. No one was trying to tell the story of 1971 to 2018. There's a book that came out last year for Yale University's ''Jewish Lives' series, it's called Stan Lee: A Life in Comics. It's a short biography of Stan, and there's no original reporting, as far as I know, I think it's all drawn from secondary sources.

But the big thing is you read it, and the narrative you get is basically a brief look at his life before 1961, and then you have an entire book about '61 to '71, and then at the end of the last chapter, there's like a few paragraphs saying, "…and then rest of his life happened."

And I just don't know how you can write a book like that, how can you write a biography and claim that you're telling the story of the whole life, when you're only focusing on about 10 years.

And so, my mission for this was like – there was even a moment, I was having a conversation with Sean Howe, who wrote Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, right when I got the book contract. And I was asking him for advice, and I said, "For me, the most interesting part is Stan and Stan in Hollywood – you know, he moves to Los Angeles in 1980 and stays there until his death. And I find that fascinating."

And Sean said, "You should see if you can just have the book be 1980 to his death and then maybe tell the rest in flashback." And that's not how it worked out, and I don't think that actually would have worked as a book, but his heart and his mind were in the right place, which is that's the meat, 1980-onward.

That's the stuff that hasn't been told. And I think it's the most revealing! That's a huge chunk of time in which this person really revealed themselves for who he was in a lot of ways. And I just, I guess I'm lucky no one else had looked at it before, because that makes it look like I have a lot more original ideas than I probably actually do.

But on the other hand, it's kind of frustrating that so long for so long people just didn't look at that area.

Nrama: Abraham, what did you see as your job when you took on writing the book?

Riesman: My job with this book was basically to find out the story and then get out of the way of the story. Sometimes when you're writing something, you have to take details that are mundane and explain to the reader why they're interesting, but not in this case. I just had to tell what I found, after I'd sifted through the BS to the best of my ability. And that story is just fascinating.

That's not me being a great storyteller. That's the fact that this guy lived this life that was so rich with contradiction, and drama and betrayal and love, and the highest heights and lowest lows. And that's just fascinating, and you want to just let that happen. And again, it feels frustrating when I read other accounts of Stan's life, be they articles or books, that just sort of yada yada yada away the parts that are hard to look at.

Nrama: But there's a certain Greek, or rather Shakespearean tragedy to elements of these details.

Riesman: Absolutely! I mean, obviously I agree with you because I opened the book with the epigraph from Macbeth, "I have no spur/To prick the sides of my intent, but only/Vaulting ambition, which o'erleaps itself,/And falls on th'other. . ." And this is a story about ambition.

I think that was even how the outline I wrote when I got the book contract, that this was a story about ambition. Because it is! This was a guy who was talented at some things and untalented at other things. And the one constant was he always wanted to be more than he was.

You know, he always wanted to present himself as this jolly person who was also kind of an apex predator, this guy who was important to it, who had birthed something, and who had risen to the highest heights. And that ambition really drove him to do some amazing stuff, and to do some unsavory stuff. And ultimately, ambition can only take you so far in finding happiness. And he ended up having this really rough last stretch in his life.

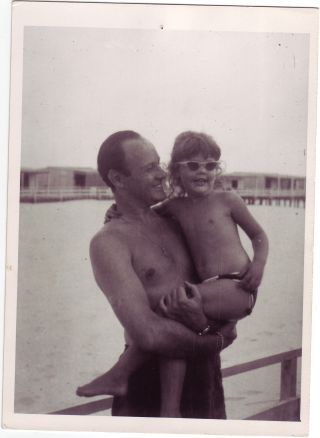

Nrama: Which reminded me a bit of King Lear with J.C Lee, his daughter...

Riesman: Yeah, it's…I mean, you run the risk of cheapening bad things by comparing them too much to fiction – I'm not criticizing you, it's always a risk for me – but absolutely. I mean, there's a degree of conflict between parent and child that…let's just put it this way: Everyone would rather that that was fiction, than have it be their own family.

You read about the stuff that was happening between Stan and J.C., or you hear the recordings I heard that Keya Morgan played for me into headphones in suburban Los Angeles, and you hear them screaming at each other and falling into deep, passionate hatred that I'm sure is rooted in love, but is very ugly to listen to.

And, yeah, it's a bit like King Lear, but also, it's the kind of thing you wish would only be in King Lear. Unfortunately, in Stan's case, that was something he had to live with.

Nrama: It's funny what you said about fiction there. Sometimes, I just read so much stuff that I feel like I'm only able to understand a lot of things by what fiction I can compare it to.

Riesman: I have to hold myself back from that.

Nrama: It's just nice to have somebody openly admitting that. [laughs]

Riesman: We look through the lens that we look at a lot of stuff through, but it's dangerous because these are real people's lives, and this was real tragedy. This was not Shakespearean tragedy. It was an actual case of extended elder abuse. Well, it's hard for me to pinpoint with certainty who the exact abusers were, but there's no doubt he was getting abused, and it's just really, really sad.

Nrama: And yeah, there's just a whole series of toxic relationships toward the end there…

Riesman: He kept getting into bed with people who took advantage of him.

Nrama: When you started the part about one of his business partners Peter Paul in the book, I found I found myself going, 'Man, I wonder I should ask if he wants to write a sequel about Peter Paul,' and a few paragraphs later, you admitted to that!

Riesman: You could write a whole book about him! Peter Paul is one of the most fascinating people I've ever encountered in my life. Again, this is a case of just, it was so interesting on its own that I just had to get out of the way. You just present what Peter tells you, and as long as you disclaim by pointing out that you can't prove most of this is true, because most of it is so deliriously unprovable, but it's all there and it tells you something. The fact he's talking about it tells you something about him. And it's hard to sift through all of it.

I was nervous writing that chapter because, I don't like having people take over my article or my book with their quotes and take you on a journey with them where I can't actually back up what they're saying. This is a reason why I'm always skeptical about oral histories. People will say like, "Oh, here's the oral history of X," and they have a long blockquote of somebody saying the story, and you can just get away with putting that in there and not actually back it up.

You have plausible deniability. You can always say, "Well, I didn't say it happened, I'm just quoting what somebody says."

And that's fair. Unfortunately, that's how journalism has to work, because facts are little fractals. You can always end up researching and researching and researching to find out what the truth is. And truth is this slippery little thing that is very hard to determine.

But the fact is, when you let somebody like Peter Paul occupy that much real estate with his quotes, you're running the risk of having the reader really go in and say, "Oh, well, all this must be true," because readers are often credulous.

With that chapter I had to really put in an effort to make clear with everything that was being said took the form of, "This is the story Peter Paul told me." I can't – literally, I can't verify whether any of it's true.

I filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the CIA, the FBI, the NSA; I reached out to government agencies saying, "Do you have any records of Peter Paul being involved in these covert activities?" And they never got anything back to me. So, that's the best shot I could possibly have had really verifying any of this, but like…

Nrama: You didn't want to turn him into like the Joe Exotic of the book, this figure whose eccentricities overwhelm the narrative?

Riesman: Exactly! It's more like the Joe Exotics of the world have gotten such a free pass lately and that we let them tell their stories, and we don't necessarily ask whether they're true or not, it's just entertaining to listen to them.

And I want this to be a thing where I'm not just entertaining you with this crazy, possibly untrue chain of events that Peter Paul told me. I wanted you as the reader to be asking questions like, 'What is this telling me about him?' I want the reader looking at that section and going, 'I understand this guy more,' not 'I know what happened in his life,' but 'I understand it more.'

Nrama: People can tell you a lot about themselves even with their untruths. It reflects on who they are.

Riesman: Absolutely. That's one of the main things that's interesting about Stan. That's the big challenge and opportunity of writing, especially about Stan's young life, which is, there's stuff we'll never know. Stan didn't grow up as, like the princely son, the duchy. He was not researched and analyzed from his earliest age. We only have his word, and the word of his brother Larry Lieber, who was unbelievably generous with his time with me. And that's about it.

And you know, them's the breaks. All I can do is look in archives, see if I can find stuff that backs it up, but of course, archives are unreliable. I don't mean to send you through like an epistemological spiral right now where you can't discern what's real and what isn't, but that was kind of my existence while writing this book.

Nrama: That's why I have a really hard time doing research projects, because there's always what you don't know, what you could find, what's not provable... you feel like you're in The Matrix by the end.

Riesman: Right! 'Who don't I know?', 'What do I know exactly?' and like had never plagued me the way it plagued me while working on this book. Because people are looking to you as like an authority. And it's not like I didn't check facts before this book, but you only have so much time with an article, whereas with a book you have more… I mean, I didn't have that much time, we had about a year to write this thing. But you have a longer stretch of time where you can delve deeper, and the more you learn, the more you realize how uncertain you are.

I say that in the introduction, that Stan Lee's story is where objective truth goes to die. There's a lot in there that you just can't verify or conclusively deny.

And that's very frustrating, but I tried to be honest with the reader in this book and just say, 'Look, I'm going to tell you what I heard, I'm going to tell you what I heard from other people about what I heard, I'm going to tell you what the archives said, and then beyond that go forth, I can't help you any further, you have to come to your own conclusions.' Or, you can be like me and just say, 'Unfortunately, we'll never know when it comes to certain things.'

Nrama: Well, isn't that like really knowing almost any other human being…okay, I'm in The Matrix now. Sorry.

Riesman: I know! I know! But that's the thing. The Stan Lee story is a real challenge, because there's so much deception there. But it's almost like an advantage because at least you're looking for deception. You're not going into the story, at least if you're me, saying, 'I'm gonna take this person at his word.' Your Spidey Sense is tingling already. And then, if you're paying attention, this Spidey Sense keeps tingling and you start to find out a lot of stuff that otherwise you would have just not known, because you would have taken the official story as a given.

So, anyway, it's all a long way of saying history and journalism are really hard. We act like it's easier than it is because it helps us feel safe at night. The fact is, nobody knows anything.

Nrama: William Goldman immortalized that phrase as it applied to show business.

Riesman: Yeah, exactly. Right.

Nrama: Do you have any other in-depth work in comics you can talk about at this time?

Riesman: Right now, I don't think I have anything comics-related happening. I sort of felt like this book is going to be me hitting pause on comic stuff for a while, just because I kind of overdosed on it to a certain extent, and I have to work on other projects that are in other veins, but I'm struggling to think of anything that's in the comics realm that I'm working on right now.

I am, you know, writing. My main project is I have a second book, this biography of Vince McMahon that I am working on, and I have articles that have nothing to do with comics that I also write, outside of that world.

One of my main jobs is hustling for this book, because I have a wonderful publicist, but they have a million other things on their plate. So, just a word to the wise for prospective future authors, you're gonna have to do a lot of hustling on your own, which in my case I actually enjoy. I like connecting with people, and I'm a theater kid, so I like kind of putting on a song and dance show for people. But that takes up a lot of time. There's a lot in negotiating and following up with people and reaching out and working connections and getting to know people and exploiting them. [Laughs]

But yeah, that's it!

Look back at Stan Lee's greatest Marvel Comics creations.

Zack is a comics journalist, who has written primarily for Newsarama, GamesRadar, and Indy Week. His words have also appeared in The Washington Post, AXS, VOX, The Sports Network, Gambit, and more.

Most Popular