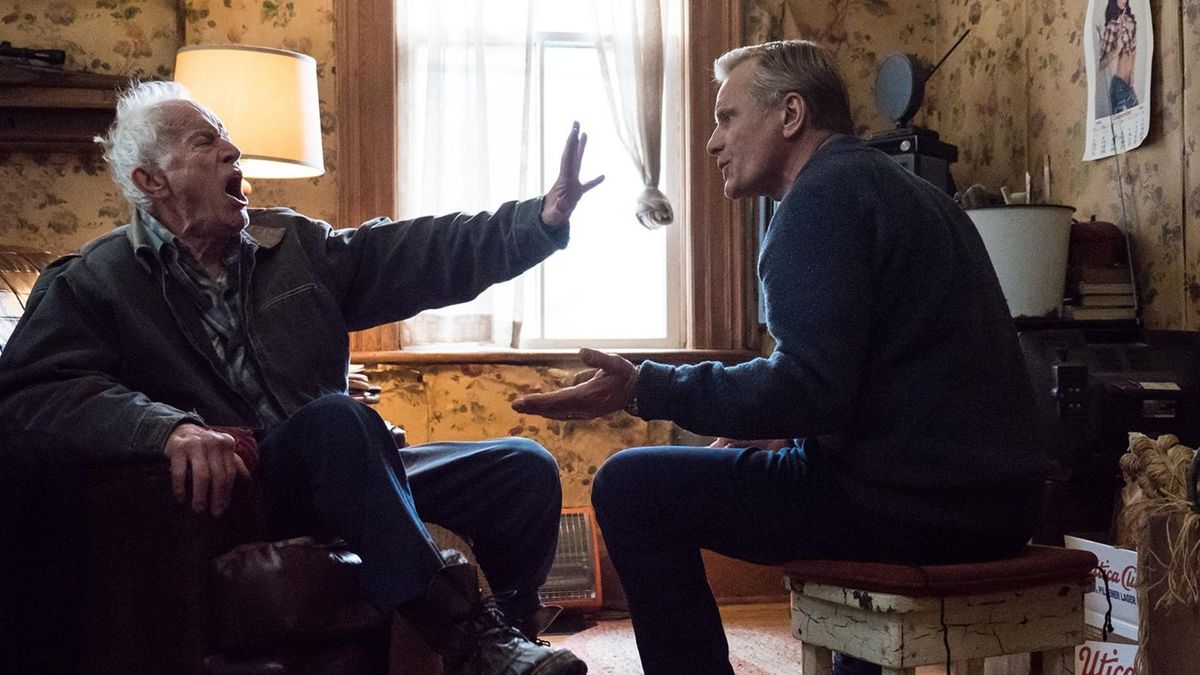

Viggo Mortensen and Lance Henriksen on why Falling was the hardest movie they have ever made

The actors behind Aragorn and Bishop talk to 12DOVE about their latest project, Falling

Viggo Mortensen is a man of many talents. Best known for playing Aragorn in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, his latest project, Falling, sees him on quadruple duty as writer, director, composer, and actor. Add to that just how personal the script is, written after his mother's funeral and borrowing elements from his own memory, and it's no wonder that Falling is the hardest project Mortensen has ever worked on.

The movie sees Mortensen play a gay man who's father, portrayed by Lance Henriksen, is a horrible, abrasive figure suffering from Alzheimer's disease. There are multiple flashbacks, with Sverrir Gudnason playing a younger, equally horrible version of the father, while the teenage version of Mortensen's character deals with his own sexuality in a homophobic household. It's a difficult but fulfilling watch.

12DOVE and Total Film caught up with multi-hyphenate Mortensen and Henriksen – a man with over 250 acting credits to his name, though you will most likely recognise him as Bishop in the Alien movies – to discuss Falling. Below is a Q&A, edited for clarity, or listen to the interview on the Total Film podcast.

12DOVE: Lance, your performance is fantastic in Falling. You play this very abrasive father character dealing with memory loss and who has few redeeming qualities. I’m wondering: how did you find empathy with that character?

Lance Henriksen: A very basic part was that he just wanted to be left alone, and not fixed. That gives you the right to hang onto your life. Because if you give it away, if you give that reality away, there’s no assurance that I’m going to have a life of any kind, you know?

I mean, that’s the simple answer. That’s the surface of it. Because, really, I am not authoritarian with my children. I never have been. I never wanted it, because I had been through so much of that kind of thing as a kid, that I would never dream of doing it with my children. That’s part of it too. It’s where I came from. It’s part of that.

I understand that Viggo wrote the film after your mother’s funeral. The movie sounds very deeply personal to both of you. Is it difficult, therefore, for both of you to expose yourselves on screen in that way? Especially, Viggo, this is your directorial debut as well. It feels personal in a way that perhaps we haven’t seen in your work before?

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Viggo Mortensen: Well, in this movie’s story, a lot of the more complex scenes, and emotionally demanding scenes, and, just in terms of the dialogue and the interactions, some of the more difficult scenes were the ones that Lance and I had to perform together as actors. The fact that I wasn’t just the director of those scenes but I was in the scene on an equal footing with Lance, and because we had gotten to know each other in the years previous to shooting – because it took a long time to find the money to finally be able to shoot the movie – we had gotten to know each other, and trust each other, and share personal stories with each other.

And as actors, I think we have a similar approach in that we never want to be caught acting. You want to get to the heart of the matter – no matter what it takes, and how uncomfortable the experience might be, or what you’re trying to portray is – in an honest way.

Being that we were both in these scenes, we were having to solve those problems and overcome those obstacles together. It was difficult sometimes. It was as difficult as I thought it would be, but it was even more satisfying than I had hoped it would be to work together on those complicated scenes. I really enjoyed it.

And without Lance, and the subtlety and courage that he brought to his portrayal, the movie really wouldn’t work in the way that it does, I don’t think. I think that it’s an extraordinary performance that Lance gives.

Henriksen: Thank you, Viggo. But listen, I was trying to give you a simple answer, because, in the film, it has a lot of layers and a lot of lines of truth with all the characters. They’re truthful. It’s not meant to be bludgeoning your family. But [my character gives] the reaction of an animal, in a way. There’s an animalistic part of this thing.

Mortensen: The story is a lot about how difficult it is sometimes to communicate with certain individuals in your family, or in your life, or even your professional life. There are some people that just don’t want to find common ground with you, or don’t seem to want to. Or maybe they’re afraid to, or maybe they’re just suspicious. It’s very difficult to find a point of contact.

Sometimes you don’t get there. The story, in a way, is about that. It’s about the difficulty of communicating with certain kinds of people, and the difficulty of accepting them, and accepting yourself as you are, and as things are.

In a way, it’s a story about losing – having lost love, and understanding, and trying to regain it. You may not entirely regain it, but you may make some little progress. There’s no guarantee. If you’re as stubborn about trying to communicate as the other person seems to be about not wanting to? You might not. You might. But there’s no guarantee.

Henriksen: It’s been about a year since we filmed this, and it still lingers. It lingers that I’ve been through something. It’s like maybe getting out of prison, and not wanting to remember what it was like [laughs]. It was very intense. I don’t mean that it was a prison or painful. It wasn’t.

There were incredible things that happened that will fulfil you for the rest of your life, that happened during the filming. There are some elements in there that we all resonate with. I’m an actor, so I’m willing to take chances and dig into things that I wasn’t expecting.

The core of it was that Viggo had written this amazing script – a complicated script – and he went through the whole thing with us again. He wrote it, and now we’re filming it. And he’s going through it with us again. That was an amazing support system. So we could take chances, and try to come up with something – like you said, you don’t want to get caught acting, in a thing that’s all about passion and confusion and all of those hard things to act. I certainly wasn’t acting at all times. I wasn’t doing that at all.

There’s this phenomenal confrontation scene towards the end of this film between your two characters that’s draining just to watch. I can't imagine being one of you two within that context. It’s quite an experience. Lance, we’re more used to seeing you in those action roles – Aliens and Terminators. This feels like a really meaty role. Is that the sort of scene you kind of crave as an artist to be part of and to do, or is it more of a draining experience?

Henriksen: No, no. It’s draining and it’s something that you want. You want a challenge. Because we don’t know what we’re capable of until we get to challenge. We don’t know. We can imagine what we would like to do. I would like to be a pirate swinging on a rope from the top… [laughs] But it was a gift, because it made me remember and reconcile with a lot of my youth, and my blundering through life.

And acting gave that to me. Before I was an actor, I was wanting to be an artist. I wanted to paint. But secretly, I wanted to be an actor as well. Because I felt that whenever you have an exchange like we’re having now, we’re trying to give the best of ourselves to this moment. And that’s what acting is. You want to do that. You can learn from it. And make a living, by the way.

An interesting thing about this is obviously, for Viggo, this is your first time as a director. Working on something you wrote, directed, did the music for – has it given you a renewed appreciation of some of the other directors you’ve worked with in the past?

Viggo Mortensen: I certainly benefited from what I’ve observed and learned from working with some – I’ve been fortunate – really good directors. With David Cronenberg (who also plays a minor role in Falling) and Jane Campion… it’s just a vast array of very talented people. Peter Jackson, Matt Ross, Peter Farrelly, David Oelhoffen, on and on, men and women from different countries, different cultures, with different approaches, different tastes.

And yet, all of them prepared what they were going to do really well, and communicated openly, and without being insecure, in a really constructive way with their crew, with their cast. In other words, they made the most of the opportunity that they had.

I took that on board. We prepared the movie really well, because I knew we would have a short time to shoot a very ambitious story in winter, with limited daylight hours, and lots of children who have limited work hours, and different time periods, and some very long scenes and very complex, difficult scenes.

So preparing was important. And on the first day, as I said to the cast and crew, I said, “We’re going to do this together. We have one shot at it. We have one chance to make this movie. Just because I wrote this story, and I have a very clear idea of what I want to attempt, it doesn’t mean I have all the answers. And if you have a question or suggestion about anything we’re doing on any given day, please speak up. Because a good idea can come from anyone at any time. Please don’t do it the day after or the week after we’ve shot the scene [laughs]. Now’s the time. Every time, now is the time. So don’t be shy. I’m not going to take offence at any suggestion. We’re doing this together.”

And that’s what we did. And that is because I learned that that’s the best way to do it. But I have to say, sometimes, if you’re talking about that scene that you were talking about previously with Lance, which was a very difficult scene – there are certain points during shooting that you have ups and downs. I think Lance had them too.

I remember, there was one day where Lance was saying, “I think this is going to be my last movie. This is kicking my ass.”

And I said, “Yeah. This has been interesting. I don’t know if I’m going to direct anymore.”

We had a low point which we shared. It’s always good to communicate. And then we moved on. And then the next day, we solved the problems to that scene, and suddenly we’re on fire again, and happy to be doing it. But we were together, and we were communicating throughout.

But I have to say, there were moments where I thought, “Why did I write it this way? Why did it put this challenge in front of us? This is horrible! We are so uncomfortable, and we are going to be uncomfortable all day trying to get there. Because if we’re going to be honest, this has to be difficult for us. If we want it to be difficult for the audience, that’s what we have to do.”

It was worth it. But there were times it was difficult.

Henriksen: I remember us standing in a parking lot, and the sun had set, and it was cold up in Canada. Freezing cold. And it matched where we felt we were at. We were just at the bottom. I don’t think it can happen in a flop story. I’ve gotten away with a lot as an actor. I could handle a lot more than they thought I could. But in this case, because of the affection I had for Viggo and what we were attempting, I had to be honest, and I said to Viggo, “I think I’m going to quit acting. I’m done. I don’t know if I’ve ever felt this low in my life.” [laughs]

Mortensen: We were living in Bleak House.

Henriksen: [laughs] Bleak House is right. He left a note in my trailer with a rose on it. A white rose. It said, “This is supposed to be fun. So let’s have some fun. Tomorrow, when we come in, let’s have fun.” And we did. We didn’t have fun to the point of messing up what we needed to do, but it sure lifted us both up. I think it lifted him up to the write the note, because he even said to me, “I don’t think that this directing thing is… ugh.” [laughs]

But looking back… the pain of birth – if women really remembered everything about the pain of birth, there’d be no children. But you forget. The next day, you forget. You go, “Let’s plunge at this again.” Because we know we’ve got something. We knew it. We felt it.

What an experience. This is a lifetime experience. This is the one I was waiting for, to confirm that acting is worth doing.

Would you then say that this was one of, if not the toughest, artistic endeavours you’ve gone on then?

Henriksen: Yeah. Without a doubt. No doubt.

Mortensen: It was every bit as difficult as I thought it would be, but it was more satisfying personally and in a collective sense between me and Lance and everybody that we were working with than I dreamed it could be.

Henriksen: I was afraid to ask.

Mortensen: What?

Henriksen: I was afraid to ask, “How hard is this going to be?” [laughs]

Mortensen: [laughs] Yeah, I could feel it from him. I remember, there was one point, the first time the movie fell apart, and then I came back to you about a year-and-a-half or so later, after trying to get another movie script made into a movie, and that didn’t work either – I couldn’t find the money. Not enough.

I said, “Lance, I’m going to try again.” I called him up, and I said, “I’d just like to know if you’re still with me, and this story. Would you like to try again with me?” And he didn’t say anything. I said, “Lance, are you there?” He said, “Um… um… yeah. Yeah. I want to do it.”

I said, “Well, that was a really long pause. It’s OK if you don’t want to. It’s no problem.” And he said, “No, I do. I just know it’s going to be hard.” And not just hard in terms of the role – which is extremely demanding. I can’t imagine anyone doing what Lance did with it. I mean, it’s beautiful, layered, profound, brave. Just all the way. He went all the way with it.

Maybe Lance can speak to this. He saiid: “To be honest, I am going to have to go back. I’ll have to remember some things about my childhood, and my feelings about that, and my memories that are complicated and that are difficult. This is going to be a tough sledding. But that’s OK. I want to do it.”

Henriksen: You know the pauses between events in your life? There are pauses, right? They could be a year, they could be a month. We do that to save ourselves, our sanity. We pause. “Put that on hold. Put my life on hold. I don’t want to delve into it, because I don’t know what will happen.”

We are all a fragile machine. They call our brain the soft machine. It does its own thing, and then we hang on for dear life. Look at the coronavirus right now. People are responding with the soft machine and don’t know how to control it. They’re making all kinds of mistakes. Look at Trump [laughs]. A soft machine.

Mortensen: It’s interesting that you bring up the pandemic, because I think more people than usual, many more people, are conscious on an almost daily basis of how fragile, how precious, how fragile, how uncertain life is. It always was, and always will be. But we don’t usually think about getting sick and dying all the time, unless you’re very old and already sick or something.

And people don’t – especially young people – don’t think about that, and don’t think about old people either. They walk down the street. If you’re a kid who’s 15 or 25, you might see an older man or woman sort of struggling down the street or something, or someone in a wheelchair. You might glance at him and go, “Oh, wow.” And then you’re onto music and sport and other younger people and what you’re doing tonight…

Henriksen: They’re invisible.

Mortensen: Right. They’re invisible. And that’s natural in a way until you get older, or you experience caring for someone who’s older. But now, with the pandemic, even younger people might see an older person and go, “Oh, I wonder where they’re going? I wonder who’s taking care of them? I wonder where they live? I wonder if they’re afraid of being sick?”

And I think that’s positive. I think it’s good, and it also adds a layer to the viewing, I think, of a movie like Falling, because people are more aware of the importance of honest and open communication now than ever. Most people are. And I think that’s a positive thing. People are thinking about it in a different way. I know I am.

Henriksen: I am too. I really am. I’m starting to see the mechanics of our lives. The mechanic is: we buy something. Now we own it. We don’t have to think about it again. There’s a whole series of behaviours that we do as people that we never thought about before. We just never had to.

It’s a very commerce-oriented world that we’re living in. If you notice, even, on the internet, there’s more ads than have ever been on radio. And there’s dumbass ads. [laughs] They’re trying to sell us a thing that you put in your mouth to make your jaw look bigger. I mean, what is that? It’s a little exercise rubber. I mean, where did that come from? And who needs it?

Mortensen: I haven’t seen that one [laughs].

Henriksen: A guy said, “Look at me. I’ve completely changed.” And the pictures are identical.

I think the ads that are aimed at you are depending on what you’ve searched before...

Henriksen: [laughs] We’re so busy with commerce that we’re distracted from the reality of life. That is what is apparent. I saw a guy once, an old man, fall down while getting on a bus. People in the line waiting for the bus, stepped over him to get onto the bus. I went, “What? No one’s helping him up?”

Mortensen: Was that New York City?

Henriksen: Yeah. New York. I grabbed him by the shirt and went, “Come on, let’s get on the bus.” But they were stepping over him. I thought, “Wow.” I’m not a saint. I wasn’t a saviour. But it was like, “This is bullshit.” Excuse my French.

Your character in Falling is very much a part of the silent generation, and there’s a different way of. This film takes place within the Obama era. What would have happened if this had happened in the Trump era? How would, Lance, your character have reacted? It's an interesting thought experiment.

Henriksen: It does probe you. This movie probes you. It demands that you think about it, that you’re capable of just about anything that’s going on in that movie. You’re capable of it. Otherwise you wouldn’t be seeing it. Imagine what people are carrying from the Depression era or the Second World War, and then you see these old guys with the hats on, that they were in Iwo Jima.

If you stop them to talk to them, you would really get all of that without having to pay the price – if you talked to them.

Mortensen: When I was first writing the screenplay, it was already the beginning of the Trump era. It was when he was campaigning. My mother died in 2015, and that’s when I started writing the story, and then I was refining it. But in 2015 and 2016, when I was approaching Lance, we were getting closer and closer to him being President. I didn’t know it yet.

But the social discourse in the United States, and also in other countries, was changing already. Polarisation and all that was starting to become more of a problem and more obvious – the hate speech; the lack of communication; and people going into each of their corners, ideologically, and not seeing things the same way at all, and not even talking about it or trying to find some common ground or some middle ground. That was getting worse.

I made a choice as I was rewriting and working with Lance. And then we lost the financing. And when we finally got it going, which was in 2019, then he was already President. And I made a choice consciously to set the present in our story at the beginning of 2009, at the beginning of Obama’s first term. I think any family story, whether it’s in a novel or a movie or a TV series; any family story, with all of its complicated relationships, you’re going to think about society at some point.

Any family is a microcosm or a mirror of society in general to some degree or other. I felt that it was likely that one would also see the family story in Falling and compare it to society to some degree – the conflicts, the polarisation, and all the differences of opinion, and the communication problems, and so forth.

And I just thought: well, what is happening already in the beginning of the Trump era was that it was becoming more 24-hour news. In other words, if Trump succeeded at one thing, it was getting people to talk about him day and night, every day, seven days a week, all the time.

Then if the movie’s present time was set in 2018 or ’19 or even ’20, you would think about that all the time. Because back in 2009, people were still talking about other things and other countries and history and culture and climate change and life and sports. It wasn’t the same thing on and on, and only this person being talked about, and the ramifications of his behaviour and his language.

I figured you’re going to think about it anyway, and that potential for polarisation existed already during 2009. But I felt it was better to set it then, and then people could make the comparisons they wanted with society and the world anyway. And they have. Which has been an interesting conversation at some Q&As and some of the interviews Lance and I have done, talking about that issue.

But it’s almost like it’s become another pandemic. You’ve got the viruses, like COVID-type viruses that are dormant, that are always there – they don’t completely disappear. There’s always the potential for a big outbreak, a big global pandemic. And it’s the same thing with social interaction and communication. When it disintegrates and people stop talking, and there’s a lot of polarisation, that’s almost like another virus. And it is infectious. It’s contagious.

And right now, the pandemic of poor communication or no communication is just as serious, and it’s going to probably be more long-lasting than the COVID pandemic. It’s going to be around for a while. And every new generation has to deal with these problems to some degree or another. But right now, around the world, not just in the United States, but the pandemic of bad communication and a lack of understanding and effort to understand each other, is at an all-time high I think. It’s pretty bad right now.

Falling is out now.

Jack Shepherd is the former Senior Entertainment Editor of GamesRadar. Jack used to work at The Independent as a general culture writer before specializing in TV and film for the likes of GR+, Total Film, SFX, and others. You can now find Jack working as a freelance journalist and editor.