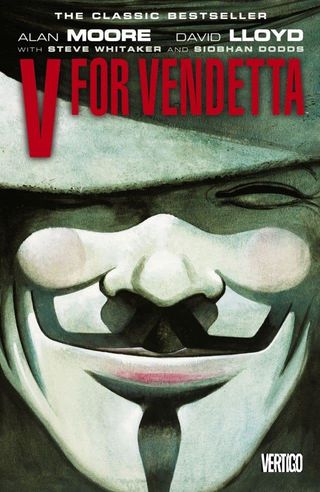

V for Vendetta "a love letter to truth, justice, and the Anarchist way"

Revisiting Alan Moore and David Lloyd's V for Vendetta

"It's everything, Evey. The perfect entrance, the grand illusion. It's everything. And I'm going to bring the house down." - V

In 1989, one of Alan Moore's seminal works finally concluded, starting off in relative obscurity and — aided by the runaway success of Watchmen, completed three years earlier in 1986 — made Moore into a legend. It was subversive. It was brutal. It was a love letter to truth, justice, and the Anarchist way — it was violent and vicarious, volatile, and visionary.

It was V. V for Vendetta.

And as his masked terrorist hero proclaimed — "Remember, remember, the fifth of November" — we're going to look back on this groundbreaking work, and its effects on Moore and the comic book industry as a whole.

Rewind to 1981. Alan Moore has yet to strike paydirt with Watchmen, which would go on to be one of the most celebrated and well-known graphic novels of all time. Instead, take a look back to the creation of a black-and-white British anthology that would go on to make history: Warrior. With editor Dez Skinn, Warrior housed many of Moore's great works, including the subversive superhero epic Marvelman.

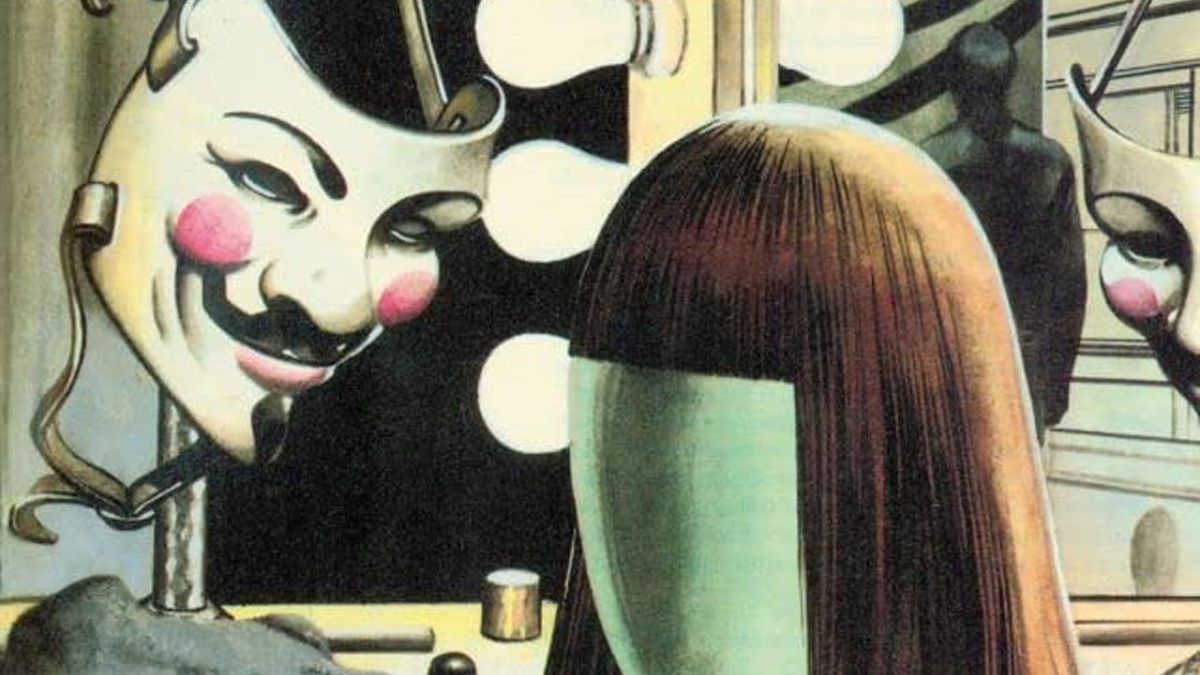

But the very first issue of Warrior — headlined by Axel Pressbutton, the Psychotic Cyborg — had a cloaked man with a Guy Fawkes mask along its spine. "V for Vendetta." It was a short first chapter, but it was effective: Evey, a munitions worker so desperate she's decided to sell her body on the streets. Unfortunately, her first solicitation happens to be a Fingerman, one of the corrupt policemen in a totalitarian England. She is only rescued from rape and worse by the intervention of V, a masked terrorist whose dispatch of the men is as brutal as it is inventive.

How did that come to be? In an interview with Warrior later reprinted in the V collection, Moore recalled that the idea for V actually was a descendant from an idea he had when he was 22: 'The Doll.'

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

The Doll was a masked terrorist who waged war on a totalitarian United States. Despite sending the idea to a scriptwriter talent competition — perhaps not surprisingly — the idea didn't fly.

"D.C. Thomson decided a transexual terrorist wasn't quite what they were looking for," Moore recalled, "and wisely opted for an entry submitted by a green-grocer from Hull entitled 'Battler Bunn (He Bombs The Hun!)' or something very similar."

Despite feeling crushed that his work hadn't been approved, Moore still managed to make friends in higher places — namely, artist David Lloyd, who had collaborated with Moore on strips for Doctor Who Monthly. When Lloyd was brought on board for Dez Skinn's new operation, he suggested Moore as a writer.

The two's partnership was both electric and incremental — for example, despite Moore's exhaustive research on the '30s gangster era, Lloyd said that if "he was called upon to draw one more '28 model Dusenberger he'd eat his arm."

Yet as ideas were kicked around — Would the setting be England as opposed to the US? Would the character be called 'Vendetta'? Would he be a cop trying to bring down the system from within? — Skinn associate Graham Marsh gave them the title 'V for Vendetta,' what Moore would call "a sign from the gods."

More would come — despite Moore's dystopic touches, it was Lloyd who came up with the unique visual for V himself.

"Re. The script: While I was writing this, I had this idea about the hero, which is a bit redundant now… I was thinking, why don't we portray him as a resurrected Guy Fawkes, complete with one of those papier-mâché masks, in a cape and conical hat? He'd look really bizarre and it would give Guy Fawkes the image he's deserved all these years. We shouldn't burn the chap every Nov. 5th but celebrate his attempt to blow up Parliament!"

It was golden. Moore and Lloyd's work was groundbreaking, as it got Moore, in particular, a shot at the big times — DC Comics. In 1983, Moore was writing Swamp Thing, moving onto icons such as Superman in 'For the Man Who Has Everything' and Batman in 'The Killing Joke,' and would soon move on to the pinnacle of his career — Watchmen, which began publishing in 1986.

It was ironic that as Moore's star was on the rise, V was nearly in danger of winking out of existence. While V for Vendetta was still publishing at a steady rate, Warrior was suffering from problems with the rest of its creative team. Marvelman was under fire from Marvel Comics, and other Warrior artists went off the board completely. Warrior had had its day, and shuttered in 1985, leaving V without a home.

This continued for years, despite several publishers' attempts to convince Moore and Lloyd to take the series to its completion. Three years later, in 1988, DC Comics staged a coup, reprinting the original black-and-white Warrior strips in full color, as well as completing the series. By this point, Moore was a sequential art rock star, with Watchmen having been issued in trade — nothing to sneeze at at that point — but he was starting to chafe at his new patrons, citing issues with royalties and a proposed rating system. By May of 1989, V finished his run, having his final victory against the totalitarian government — and then Moore left DC.

Since then, however, V has kept on kicking. Despite the continuing conservatism in England — which Moore thought would be a thing of the past well before the series concluded — the series was well-regarded as one of Moore's early hits. Yet when conservatism spread around the world in the days before — and especially after — 9/11, suddenly the idea of V as a visionary became more marketable than ever. Warner Bros., DC's corporate parent, looked to this work to ride the comics film boom, working with the Wachowski Brothers of the Matrix fame to adapt this work to film. Moore, however, was livid, having already been burned on train-wreck adaptations of From Hell and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen — he called the screenplay "rubbish," telling the New York Times, "I don't want anything more to do with these works because they were stolen from me — knowingly stolen from me."

V for Vendetta was not an easy film to put together, as not only was the film delayed due to a June subway bombing in 2005, as well as having Hugo Weaving not join as a replacement V until the fourth week of production. Still, despite its many liberties — including twisting it an in arguably American-centric view — V for Vendetta went on to make $132 million worldwide, earning 73% on Rotten Tomatoes. While David Lloyd was reportedly thrilled with the production, the producers did follow Moore's instructions, leaving his name off the final credits.

Since then, V has had his image appropriated elsewhere, ranging from the progressive metal band known as the Shadow Gallery, to the Internet group Anonymous, who donned V's iconic mask in various protests and activist events.

In many ways, V for Vendetta is a tragedy both on and off the page, instilling feelings of rage and hope in both its creators and its readers. As an early work of a comics master, V for Vendetta is a book that no comics reader should do without.

David is a former crime reporter turned comic book expert, and has transformed into a Ringo Award-winning writer of Savage Avengers, Spencer & Locke, Going to the Chapel, Grand Theft Astro, The O.Z., and Scout’s Honor. He also writes for Newsarama, and has worked for CBS, Netflix and Universal Studios too.

Most Popular