The clone wars, it seems, are far from over. The practice of copying the essence of a popular game and repackaging it for financial gain has been around almost as long as videogames, but it's become a particular problem in recent years on mobile platforms.

Not only can this be dispiriting for creators, in the worst cases, clones can overshadow an original game's performance on storefronts – as in 2018, when Hole.io, a knock-off of Ben Esposito's Donut County, shot to the top of the iOS App Store before Esposito's game was even released. Sometimes, developers even find themselves competing with copies of copies, as in the case of Threes, the puzzle game which was copied as 1024, then not one but two games called 2048.

Attack of the clones

This article first featured in Edge Magazine – check out subscription options at Magazines Direct

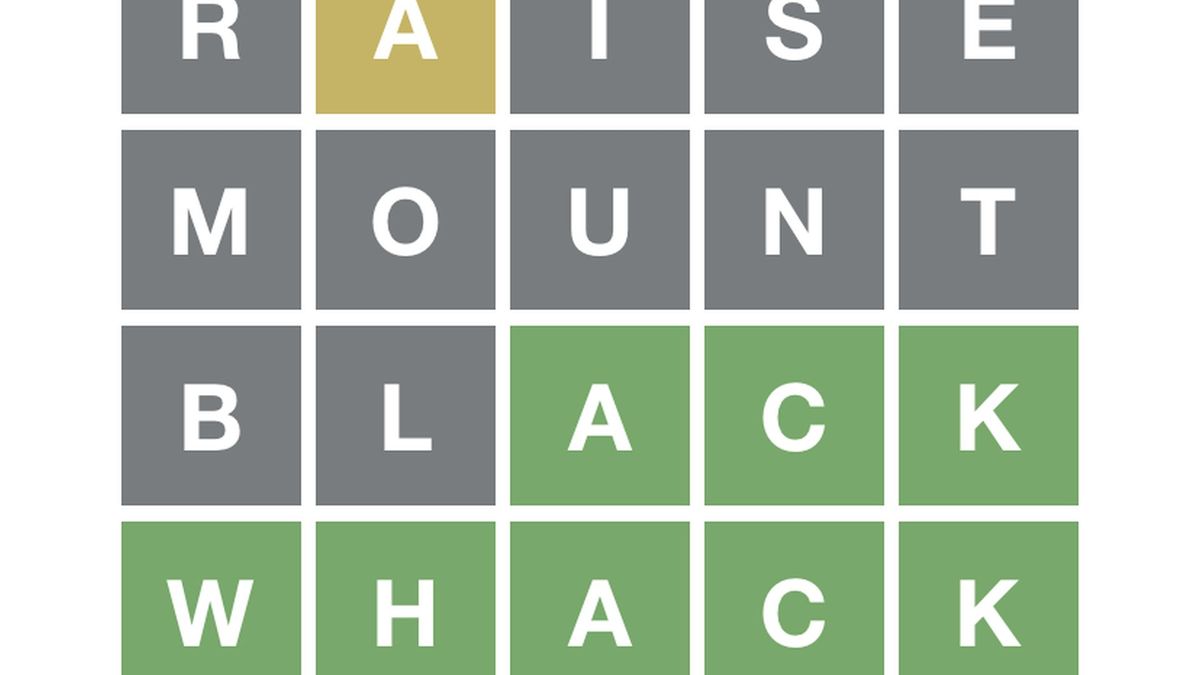

At the beginning of 2022, the conversation around cloning was reignited by two high-profile cases. When Wordle became a viral success, it launched many imitators, most offering their own spin on the concept, whether it's requiring the player to complete multiple puzzles at once or limiting its dictionary to words themed around Taylor Swift. But while these stick to the spirit of Josh Wardle's free web game, one developer capitalised on its success (and lack of trademark) to create an iOS app of the same name, mimicking its design, with the addition of a $30 subscription.

Later the same month, independent developer Witch Beam's social media channels were flooded with messages from fans, who had seen adverts for a game called Unpacking Master on TikTok and Instagram. This was a clone of Witch Beam's 2021 hit Unpacking, using what appeared to be directly traced assets – and by the time it came to the studio's attention, the game had topped the App Store's download charts.

In both cases, public outcry led Apple to remove the clones from its store (and, in the case of Unpacking Master, prompted an apology from the company responsible, which removed the app from the Google Play store itself). But that doesn't mean these were harmless incidents. "It was overwhelming and upsetting," says Unpacking creative director Wren Brier. "I definitely think damage was done to our brand. A lot of people downloaded that game thinking it was an actual port of Unpacking, and had a bad experience as that game was hastily put together and full of ads."

"Brier reports an average of three Unpacking clones per week, and has reported a total of 31 so far."

In the face of this wave of cloning, the question is: how can developers protect their games, and should platform holders be doing more to moderate their stores? In terms of preventative measures, Dr Richard Wilson OBE, CEO of video game industry body TIGA, recommends that developers avoid releasing information about their games too early, and use NDAs that explicitly prohibit cloning before sharing ideas with third parties.

There are also – in theory – some legal options for developers. "Copyright protection covers the non-functional elements of a game, such as a source code and audiovisual display, but not the idea behind the game," Wilson notes. "A patent offers protection to the functional aspects of the game such as the mechanics of the gameplay. Trademarks can protect the name of a game, too."

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This might not be viable, however, for any indie developers who cannot afford protections such as trademarks until their games are financially successful. And civil action against cloners can be more hassle than it's worth – many are based in the Philippines and Indonesia. "As well as being based abroad, cloners can easily go to ground by deleting their site, shutting down inboxes to prevent you from reaching them, or pulling the game before you can get close," says Mo Ali, intellectual property coordinator at trade body UKIE. "It's important not to rule legal action out fully but, practically speaking, most indie developers are better served by using app store reporting processes to get a clone taken down."

Requiring developers to report clones isn't a perfect solution. Brier says she reports an average of three Unpacking clones per week, most of which are little more than ad-filled apps with no game content, using the Unpacking name or assets to attract users. She's reported a total of 31 so far. Understandably, then, Brier feels that platform holders "should definitely do more" to moderate their stores, and that submission vetting processes could do with improvement.

Reporting processes are getting better, Ali says, and organisations such as UKIE can help. He advises that developers learn how to spot a copycat: while cloners will make some changes to a game, most use ripped assets or mention the original's name to improve their search ranking, meaning social media monitoring and IP scanning services can be useful tools. There is hope, he says: "We've found that developers who report games quickly and effectively tend to put cloners off in the long term."

This feature first appeared in issue #370 of Edge Magazine. For more great articles like this one, check out all of Edge's subscription offers at Magazines Direct.

Emma Kent is a freelance writer and editor, and recipient of the MCV Rising Star award. Emma has written extensively for outlets like Edge magazine and Eurogamer, and is best known for her in-depth reporting on everything from mods to game communities.

Most Popular