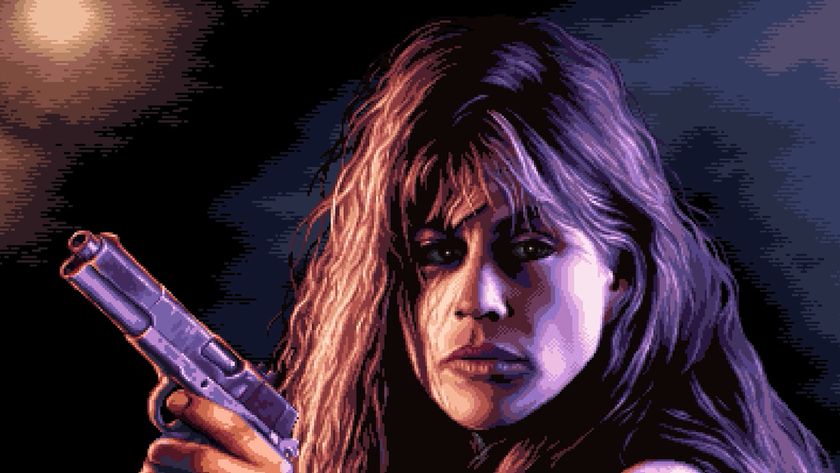

Uncharted needs to be more like Until Dawn

I like Nathan Drake. Nathan Drake is fun. As video game portmanteaus of existing film and TV action heroes go, he’s by far my favourite. Marcus Fenix might be more imposing, and Master Chief more stoically capable, but Drake’s human, self-effacing megamix of Ford, Fillian and Russell wins it for me every time. Basically he’s a great protagonist and I don’t want him to change, is what I’m saying.

Well not radically, anyway. I don’t want Uncharted 4 to deliver a hardbitten, chain-smoking Drake, with an outspoken penchant for ‘70s psych-rock and a slightly racist attitude toward the Welsh. Nor do I want Uncharted 4 to be the game that presents The Big Dramatic Turning Point for his character, those incoming interactions with his long-lost brother turning him into a sensitive poet-philosopher, mourning the loss of each and every plugged goon over the course of his new-gen adventures.

No, I don’t want his personality to change. I do though, want to change the way I interact with it. In that I want to actually interact with it, rather than simply steering it from prescribed response point to prescribed response point. Because I’ve played Until Dawn now, and I know that it doesn’t have to be that way any more.

There’s always been a tension between the two schools of video game character design, one side promoting the idea that the protagonist should merge with the player, behaving as an unobtrusive avatar and extending their will – in however abstract a way - into the game world. The other, probably more common approach – in AAA at least – is to have the player act more as a wingman to the protagonist, controlling their physical actions but remaining separate and distinct in terms of personal identity.

The former works particularly well for western-style RPGs, where the ultimate story is a cumulative mass of player-driven experiences and exploration, each micro-outcome within the growing macro-journey the result of the player’s chosen abilities and approaches. In fact it’s arguably vital. Imagine playing Skyrim or Dark Souls (Japanese, I know, but in many ways its approach isn’t) with a chatty, very deliberately designed personality chipping in during extended post-objective cutscenes. It would be an anti-immersion bungee rope snatching you back to your real-world sofa, far from the in-game body you were previously comfortably inhabiting.

In cinematic, linear action-adventures though, it’s tricky. With a specific story to tell – which logically requires specific characters – it’s generally accepted that we have to bite the bullet of occasionally being removed from the tale, of having only half ownership of our avatar’s journey. During the action, we are bonded as one, our decisions dictating the moment-to-moment play of each self-contained sequence. As soon as it’s story-time though, we must temporarily sever that connection, respecting our protagonist’s personal space as they respond and behave as they, not we, would. It can be a painful wrench at times, but you need to give the people you care about room to grow. If you love it, set it free, etc. Even if you’re just setting it free to say “Shit” a few times, and decide to blow a thing up.

A few games have tried to marry the two approaches, by way of the increasingly rare – but treasured by some – silent protagonist approach. The Legend of Zelda series has steadfastly refused to give Link any pre-loaded outlook on life beyond responding to things with excitable yelps and generally being eager to do anything asked of him. But Nintendo gets away with that by building the games around dramatically escalating objectives rather than real stories. Half-Life and its sequel are of course the tight-lipped poster physicists for this method, using Gordon Freeman’s steadfast refusal to comment on the apocalyptic events unfolding - in conjunction with smart, insightful pacing and emotionally affecting action – to fashion him into a vessel for the player’s own personality, the game’s freeform combat models allowing this unsullied sense of personal presence to be expressed through moment-to-moment gameplay.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Although effective in Half-Life 2, that series’ last entry landed mid-way through the last decade. With the next game legendarily MIA, and Half-Life’s blend of curated story and silent hero getting away with a lot as a result of the extra immersion afforded by the first-person perspective, we certainly can’t continue to laud this idea as a default working approach for all action games in 2015. We need something different. And fortunately, something different – and perfectly suited to handling the current conundrum – has just hit in the form of Supermassive Games’ splendidly schlocky interactive slasher movie.

I wasn’t being quite accurate when I said there’s a tension between cinematic story and player-driven characterisation. In truth, it’s more of a gulf, the two approaches sitting resolutely in their own separate bunkers, miles apart with the phone lines cut. As a fan of both styles of narrative, I’ve always found it frustrating that no middle ground has ever been found. After all, the history of creative innovation is one built upon cross-pollination and appropriation. But now Until Dawn seems to have made a major step toward reconciliation within one of the most unlikely, and seemingly prescriptive game designs. The cinematic, interactive drama.

Your overt choices during events – whether to run or hide, whether to save another character or make for a more sure escape with the one you’re currently controlling – will get your most immediate attention. Indeed, many players will make their way through the game paying attention to the big, button-pushing, character-killing events alone. But there’s something more interesting going on under the hood. Personality stats.

Each character has a set of starting statistics denoting the comparative strengths of core elements of their outlook. Charity, honesty, bravery, the ability to drop a sweet joke at just the right time… There are ‘progress’ bars for all of these, which grow and shrink on the fly based on your decisions in action and conversation, and also have a knock-on effect on certain characters’ opinions on each other. While it’s (usually) the more explicit events that change the course of the story, this ambient personality forge does a great deal to colour things along the way. The upshot? With my girlfriend and myself playing through the game together, we turned it into part cinematic survival horror, part dating simulator, aggressively ‘improving’ the douchier characters and pushing our preferred couples and would-be pairings together as a matter of priority.

Calm down. This is not what I want for Uncharted.

But imagine if a huge, linear, story-driven action game took on this sort of model, eschewing Until Dawn’s wholesale narrative malleability, but infusing its chosen tale with ambient player input, running invisibly, just below the surface. Imagine if some of those innocuous little gameplay choices – say, sneaking past that goon, choking him unconscious, or kicking him off a cliff – filled up an invisible set of personality meters. Now imagine if the results of these little personality tests were reflected in the following cutscenes, not changing the ultimate events or outcome, but adding customised flavour to the way they played out. Depending on how brutal, brash, quiet or clever you might play him, Drake would respond as if he’d actually been through what you’d put him through. He might be more shellshocked, or more aggressive, or lighter of spirits, or more driven.

That, I rather believe, would be fantastic. Of course, you wouldn’t notice the changes on your first play-through. But that wouldn’t be the point. What matters is how the system would ensure a much closer bond between player and protagonist, greatly reducing those jarring disconnections whenever control is handed over to the console. There would still be severance, but rather than watching a stranger take over, you’d be talking to a friend with similar outlooks, responses and ideals, or who at least behaved in a way that you could immediately understand and explain.

It would create a sense of player authorship without any of the cracks, incoherence, or general weirdness that comes along with a genuinely freeform game. The game would continue to tell the developer’s chosen story, but it would be a collaborative tale. Gordon Freeman is a fantastic container for the player’s personality, but those thoughts and feelings remain unfelt in the game-world except through imagination and action. Conversely, this method would act in the opposite direction, using the player’s choices and actions to amplify their will directly into the game, and subtly creating a protagonist who was far more ‘them’. I like Nathan Drake. I like Nathan Drake a lot. But I would like my Nathan Drake a whole lot more.

Most Popular