Time Extend: The Elder Scrolls V - Skyrim

Ostensibly, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim was about the type of tale that’s been told thousands of times before, a story of a hero by birthright bound by fate on a journey from lowly origins to world’s saviour. Players became the Dovahkiin, last of the Dragonborn, the final remnant of a people with the blood and soul of a dragon but mortal bodies, and prophecy had it that they would save all Tamriel by defeating Alduin, Nordic god of destruction.

While a suitably lofty premise for any RPG, it has nothing to do with why Skyrim continues to hover in the top 20 of the Steam charts a little over three years after its release. No, Skyrim endures precisely because its central quest and character are disposable, fading away while its detailed world creates a framework for roleplay.

Richly layered with tiny tales, almost everything in Skyrim feels like it has a story, or hides a secret: the roaring fire of a giant’s camp, the stone tower of a bandit hideout beckoning you to uncover more. Many studios fill their worlds to bursting with collectibles hoping to make them live; Bethesda instead filled Skyrim with culture and quests. The weight of the game’s history, lore and activity is so overwhelming that the player can only make sense of it through selection. And as such roleplay – not necessarily in the sense of character sheets, though Skyrim’s blank-slate hero never rejects your backstories – feels natural, a refreshing change to RPGs that cram moral choice down your throat.

That’s why players have spent hundreds of hours playing Skyrim without even touching the main quest, avoiding the drab prophecy entirely and instead getting lost in the world. And what a world it is. Situated to the north of Cyrodil, Skyrim is a harsh, chilly land full of harsh, chilly people. It’s vast – almost unbelievably so when you first load the game, sharp mountain peaks piercing the horizon in every direction. But by dotting cities throughout the land, which serve as mini hubs to break up the region and let you focus on the surrounding areas, Bethesda makes it less impenetrable.

Each of these cities has its own instantly recognisable atmosphere. Jarl Elisif sits in the Blue Palace, a collection of imposing square towers and stone domes, all tinged with azure. Arriving at Solitude from the marshes in the south, you’ll see it perched high above you on a pillar of rock, attached to the mainland by a sweeping arc of black, the sea sparkling through the chasm beneath. It’s as if an ancient giant has taken a crude carving knife to the landscape.

These places bustle, too. NPCs will stop in the streets to gossip about the latest misstep the local governor (Jarl) has made in court, or how extortionate the local tailor’s prices are. But crucially, you can be more than just a passive spectator of these snippets of life. Take Talen-Jei, who helps tend the Bee And Barb in Riften. After telling players about the “vermin” plaguing the city, the Thieves’ Guild, he admits his desire to marry the inn’s owner, Keereva, and his lack of money for an engagement ring. To get one made, he wants three flawless amethysts. Buy them and you’ll make a loss on the deal. The payoff isn’t a potion or coin, but the simple pleasure of imagining a better life for the couple.

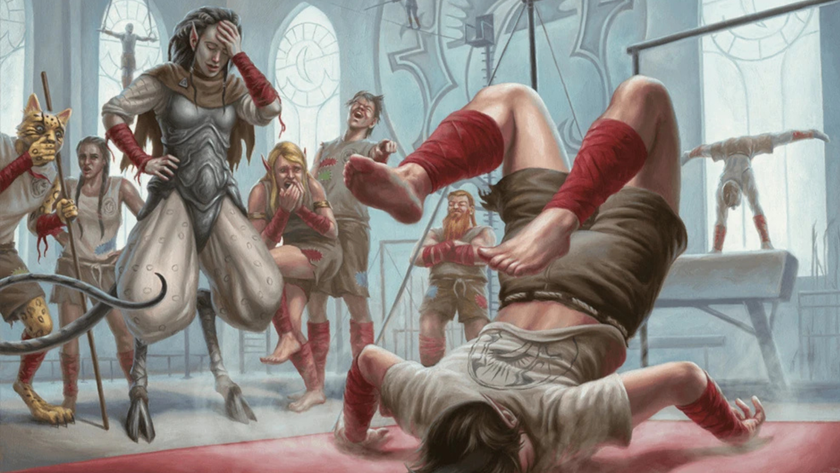

Skyrim dumps an avalanche of similar quests on you when you enter its cities’ streets. NPCs clamour for your attention, and the sheer volume of requests means you have to pick and choose who to appease. It could have come off as shallow, with quests often mechanically nothing more means to an end – the end being a weighty coin purse swinging on your belt to unload for shinier equipment. But Bethesda offers other motivations to help some and give others the cold shoulder: a particularly unusual character, say, an involving backstory, or a strange task. Taarie – one of the owners of the Radiant Raiment in Solitude – tasks you with modelling some garments for the Elisif The Fair, the city’s Jarl and widow of High King Torygg. So you, the world’s hero, end up prancing around in front of court in a sparkly outfit, asking one of the most powerful women in Skyrim if she likes what you’re wearing. It’s bizarre, but brilliant.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In making these choices, you start to build your character, decisions snowballing until you begin to have sense of what your Dovahkiin would do in each situation. Sure, some players’ takes on the hero are bipolar, flipping from helping hand to dragon-shouting a hall to pieces as the fancy takes them, but many become invested in the tale their actions weave across this cruel land. Best of all, the game doesn’t make a show of it either way – there’s nothing, other than your completed list of quests, to indicate what kind of personality your character has. It’s you, in the moment, making decisions about what to do next. Where so many games opt for binary morality decisions and love to shoehorn your decisions into a particular archetype, Skyrim’s soft approach felt like a revelation.

Not that it is uniformly hands-off. The one scripted choice the game tries its best to impose upon you – although it too can be entirely avoided – is picking a side in the civil war between the native Nords – represented by an independence-hungry group of rebels called the Stormcloaks – and the Imperial Empire. You get thrown into the conflict from the start, and are obviously pushed towards the Nords at first.

The game’s opening sets up the conflict in the starkest of terms, featuring a cart ride for a group of prisoners, of which Dovahkiin is one. In the group is also Ulfric Stormcloak, leader of the rebellion, due to be executed for killing High King Torygg. The other prisoners speak highly of Ulfric’s bravery, and even the watching Imperial general, Tullius, acknowledges that some call Ulfric a “hero”. The Imperials’ iron grip over Skyrim is clear to see. You get ushered to the block despite not appearing on the execution list, a grave injustice. That feeling is amplified when one prisoner – a mere horse thief, no less – flees in terror, only to be felled by the waiting archers.

Elsewhere, all the surface details drive you towards the rebels. Speaking to Nords, you discover that they have no religious freedom: worshipping their god, Talos, has been forbidden, with shrines removed from temples and disobedience strictly punished. The Stormcloaks seem convincing in their simple argument: they want independence, the chance to govern themselves free from the Empire’s militaristic rule.

But as you progress, seeds of doubt are gradually sown, hinting at the dangers of Nordic nationalism and bringing some shades of nuance to a world of black hearts and white snow. You might spot a Dunmer braving the cold to walk to Solitude, determined to join the Imperials, who will tell you that his kind are badly treated by the Stormcloaks and their supporters. A visit to Windhelm – where Ulfric was the former Jarl – reveals Dunmer living in a ghetto known as the Grey Quarter, cast out and chastised by the rest of the city.

If you leaf through The Bear Of Markarth, a book sprinkled throughout Skyrim, you’ll learn how Ulfric slaughtered and tortured the Reachmen, who lived in the west of Skyrim for generations before the civil war. It’s a revelation that’s especially jarring considering the Stormcloaks claim that their land should belong to the natives. Speaking to the people of Markath – itself in the Reach and the centre of the conflict – will reveal a land torn apart by the violence, all instigated by the man that you heard was a hero in the game’s opening.

It all feeds an internal struggle for the engaged player, experiencing the twists as their character does. But it’s only one of a hundred similar struggles interleaved throughout a Skyrim playthrough, most of which occur outside of cities. Do you kill an innocent traveller to grab her valuable loot, or leave her alone? Do you challenge an old Orc begging for an honourable death? Do you risk danger to free a naked prisoner from guards marching him to his death?

The choices are constant. Making these decisions, you grow over the course of your journey, finding things that interest you, shedding quests that don’t, forging an identity somewhere in this huge world. If you want, you can even eschew quests entirely, trekking round Skyrim with a bow and arrow, hunting for wolves and deer and selling their pelts to subsist.

The room for such deep character-based roleplaying is mostly thanks to Betheda’s world-building, but it’s complemented by an excellent levelling system. While it was possible in previous Elder Scrolls to take any race and mould them as you please, it took a long time to get there. For Skyrim, Bethesda abolished the class-based system, and allows you to spend perk points on specific skills, ignoring the stereotypes the races had previously become glued to. Yes, Orcs are usually big, brutal fighters with big, brutal weapons, but there’s no reason why there shouldn’t be a few who buck the trend and go on to become silent assassins.

Combine the freedom these mechanics offer with its incredibly detailed, quest-packed world and Skyrim really does allow you to live your own life, and live with the consequences, something others claim but few deliver. So despite the fact that much here is hardly revolutionary – the combat hack and slash, the stealth rudimentary, the dialogue choice limited – as a vessel for your imagination, it is revered. Perhaps that’s why players continue to shed the bonds of prophecy and lose themselves in this unforgiving land while many of its contemporaries have passed into oblivion.

After slamming D&D's Wizards of the Coast, Baldur's Gate 3 devs celebrate "good ending" for Stardew Valley mod as it gets reinstated after a "mistaken" DMCA

The Baldur's Gate 3-themed Stardew Valley mod that Larian boss Swen Vincke called "amazing" gets DMCA'd by D&D publisher Wizards of the Coast