12DOVE Verdict

This compelling exploration of war’s human cost is also a tense strategy game, with kids giving it real heart. Proof you can make an engrossing game, no matter how bleak the subject.

Why you can trust 12DOVE

Dear diary, I’m currently dying in a warzone, but I’ll try to keep this light. I actually ate a meal today. It was raw, and it’s not exactly ‘digesting’, but things are looking up. Now all I miss is a bed, friends, heating, safety, electricity, fun, joy, happiness and videogames. Oh God, how I miss videogames…

At least I’m not alone. Yet. You start this war with three survivors in a decrepit shelter, and you can switch control between them – like The Sims, but with people actually deserving of your help. You have to keep them fed, warm, rested and safe. But by war’s end, you won’t care if they’re depressed, ill and starving. You’ll just be desperate to keep them alive for another day, whatever the cost.

For better and for worse, very little is tutorialised. You’re left to figure out your survival until the war is over (the length varies each playthrough). First you’ll build obvious essentials, such as a bed and stove, then plunder the house for finite resources. You’ll make defences, vegetable gardens, water filters – the obvious goal being to make your sanctuary completely self-sufficient. It’s engaging, with that XCOM tension of constantly wondering if you’re dooming your survivors with costly construction projects.

At night, local buildings can be scavenged for essential food and resources. Many are occupied by either the armed and dangerous or vulnerable and desperate. It’s up to you how you engage them. Combat controls are stiff and clumsy (rightly so: you’re a citizen not a soldier), but all that’s stopping you plundering a defenceless old couple is your own morality.

Is stealing food from one person wrong if it’ll feed three more? What about taking bandages from a (currently) healthy person to save a wounded dweller? Playing with a heart of stone can depress some survivors (check the diaries regularly – you’ll see who’s willing to get their hands dirty), whereas helping other survivors can boost their spirits. But the game’s morals are pleasingly murky. You’re rarely punished directly, more often left to ponder how far you’ve sunk.

Days tick by fast, giving you limited time to cook meals, upgrade the shelter, make sure everyone’s healthy and rested, and that you’ve covered everything before it’s time to venture out again. This gives your decision-making compelling urgency, but quiet moments can slow the pace to a crawl. ‘Building’ something is just watching a circle slowly fill – and when that’s all you’re doing, it’s about as exciting as watching a YouTube video buffer.

It’s an uncommon flaw, as you’ll rarely be so on top of everything. You’ll want to replay this not because it’s fun, but so you can correct all the rash mistakes you made on your first attempt. If your survivors are wounded and bedridden due to your poor planning and ill-thought decisions, good luck looking away from their status screens, no matter how sedate the action gets.

If a survivor is severely hurt, they can’t scavenge. But they’re taking up a valuable bed and eating food that could feed a more ‘useful’ survivor. Scary, how quickly you start seeing them as inconveniences. We started debating whether to try getting them better, or if we’d be better cutting our losses and focusing on the others. Maybe we shouldn’t be admitting to this in print, but it’s in our more murky decisions that This War of Mine excels at showing the brutality of war.

But emotionally, it can be a little too distant. Say what you like about The Sims, but their constant babbling does give them character. These survivors are expressionless mutes. Losing someone should be an emotional gut punch, but it’s hard to get attached. Diaries are interesting, but are not varied enough between characters and unrelentingly bleak. Fair play to 11 Bit for not compromising its vision, but there’s a reason even Apocalypse Now had jokes. Even some voice acting would have gone a long way to making character deaths feel like real losses.

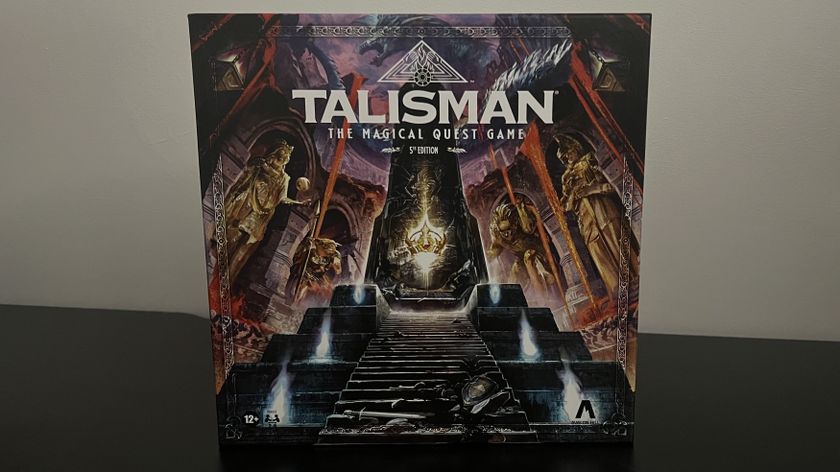

That’s where the titular little ones come in – the children who give the game its crucial heart. They scribble on walls, make cute ‘nuh-uh’ noises when you try to make them do hard labour (freeloaders), and sing as they skip around the house.

Let them charm you, and they bring much-needed levity, helping you to get emotionally involved. Lose a child to the emergency services (mercifully, they can’t die) and that loss is absolutely felt. Your dwelling will never feel emptier, the haunting score a reminder that you’ve lost the only cheerful sounds in your home.

Through trial and error you’ll learn what’s necessary and what you can live without. But the journey to mastery is a long one – our first run took ten hours, and didn’t end well. Write My Own Story mode lets you adjust the brutality of winter, how long the war lasts, and so on. Providing this easier mode wisely makes a tough game a lot more accessible, because this deserves to be played by any fan of tense stealth and engaging strategy. It’s no surprise that it’s taken so long for a game to show the civilian side of war. What is surprising is how fun it is to play.

More info

| Genre | Strategy |

| Description | A deeply serious survival-management game that shows the civilian side of war. Prepare to feel bleak. |

| Platform | "Xbox One","PS4" |

| Release date | 1 January 1970 (US), 1 January 1970 (UK) |

Tom was once a staff writer and then Games Editor for Official Xbox Magazine, but now works as the Creative Communications Manager at Mojang. He is also the writer and co-creator of How We Make Minecraft on YouTube. He doesn't think he's been truly happy since he 100% completed Rayman Legends, but the therapy is helping.

World of Warcraft guild cheats its way to winning Race for World First, gets caught, banned, then reverses its name and does it all over again

I thought I was going evil in Avowed, but one quest changed everything I thought I knew about morality in this RPG

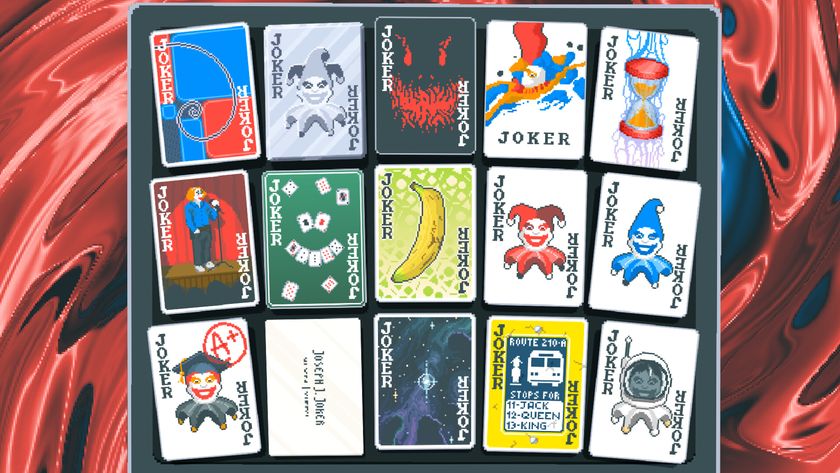

Balatro creator hits back at AI art spread on the roguelike's subreddit: "I don't use it in my game, I think it does real harm to artists of all kinds"