The Story Behind Walt Disney Pictures

The dream factory hits 50 with Tangled

A Big Future

This week Disney releases what is officially the studio’s 50th animated feature film, Tangled.

In the 70 years and more since the first animated Disney feature, Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, the groundbreaking studio has dominated the course of western animation, released a string of culture-saturating classics, and ridden several serious crises to become the largest entertainment conglomerate in the world.

Disney is now far more than just a cartoon factory, with a corporate portfolio boasting Pixar Animation Studios, several Disney-themed holiday resorts, the TV networks ESPN and ABC, comics giant Marvel and several others.

Join us as we take a look at the story behind this incredible transformation from upstart sketchers to world-straddling powerhouse.

Meet The Man

Walt Disney was and is identified with the company he founded in an almost unique way. The pair are often indistinguishable – Walt was the pioneer, the driving creative force, the moral guardian and the soul of the studio. He was personally involved in every film released during his lifetime, and the company suffered a decades-long crisis of confidence after he was gone.

He was born in Chicago on December 5th, 1901. He grew up on his parents’ farm and, after some animation work in Kansas, moved out to California with his brother Roy in 1923 to look for work. They created the Disney Brothers’ Studio, and had early success with a series of mixed live action/animation shorts based on Alice In Wonderland, and an original cartoon character called Oswald The Lucky Rabbit.

By 1927, the company had moved into new premises on Hyperion Avenue in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, and following a suggestion from Roy changed its name to The Walt Disney Company.

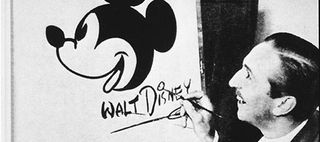

A Star Is Born

Disney is still known in industry papers and Hollywood circles as “the Mouse House”, or even just “the Mouse” (sample headline “Mouse tests waters for 3D encores”) thanks to the ubiquity and cartoon catchiness of its enduring icon, Mickey Mouse.

The star was born when Disney lost the rights to Oswald The Lucky Rabbit – and most of his animation team – during a row with his distributor in February 1928. His response was to sit down and create an even better and more appealing cartoon character, which with the help of animator Ub Iwerks, he did. Mickey Mouse made his debut in May 1928 in the short Plane Crazy.

With his circular head and two smaller circular ears, Mickey is an incredible piece of bold, striking design. Over 80 years later just the bare silhouette is instantly recognisable as the flagship icon of the whole Disney enterprise.

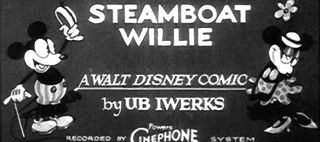

Picking Up Steam

Mickey Mouse had starred in two shorts – Plane Crazy and Gallopin’ Gaucho – before the film that made his name, Steamboat Willie. Unlike these earlier efforts, though, Steamboat Willie featured synchronised sound.

In November 1928, this was a huge deal. The Jazz Singer had given audiences a glimpse of soundtracked films the previous year, and Disney has recognised that the industry was gripped by a game-changing transformation. In pioneering the sound for Steamboat Willie, he also remade the existing Mickey Mouse shorts with sound.

Accepting and adopting technological advances turned out to be one of Walt’s strengths. In 1932 he signed an exclusive deal with Technicolor to produce Mickey Mouse and his popular Silly Symphonies series in colour. The success of these shows allowed Walt to think about something more ambitious.

The Nine Old Men

At the core of Walt’s studio team was a group of animators and directors he jokingly referred to as his Nine Old Men. They joined Disney before or during the production of Snow White in 1935, and many stayed for decades.

The were: Marc Davis, who animated Bambi and Cruella De Vil; Eric Larson, who created Peter Pan’s flight over London and trained many animators still at Disney today; Les Clark, who aided the creation of Mickey Mouse and specialised in animating the Disney icon; Milt Kahl, who created Shere Kahn and the Sheriff Of Nottingham; Ollie Jonston, who created Peter Pan’s Mr Smee and the Ugly Stepsisters; Ward Kimball, who designed both the Cheshire Cat and The Mad Hatter; John Lounsbury, a star animator who went on to direct Winnie The Pooh And Tigger Too; Frank Thomas, who animated Captain Hook and The Queen Of Hearts; and Wolfgang Reitherman, who directed all the studio's animated films from Sleeping Beauty to The Rescuers.

They are widely considered as the fathers of modern animation, and had a huge influence on younger filmmakers. Pixar director Brad Bird created cameo roles for surviving old men Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in both his debut Iron Giant and his first Disney film, The Incredibles.

Princely Ambition

Walt Disney had planned to make a feature-length animation as early as 1934. The profitability of his shorts was limited, as returns were governed by their running time (Steamboat Willie, for instance, ran just seven minutes) and he wanted the room to create stories with more complexity and deeper characters. He initially described the idea as a ‘Feature Symphony’, a musical extension of his Silly Symphony series.

What it became was Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, the first entirely cel-animated feature film in history. It was a huge gamble by Walt – a clean break from his existing characters and a massive leap for the studio in terms of both ambition and technical practicalities. Quite simply, no-one had ever done this before, and the team invented how to make animated feature films as it went along.

The studio’s staff grew to over a thousand, and production lasted three years. At the end of it, nobody was sure what the reaction would be (Walt’s wife Lillian expected that “No one's ever gonna pay a dime to see a dwarf picture”). In the event it was a terrific success, becoming the biggest grossing film of all time with a $6.5 million haul, earning Walt an honorary Oscar (one large statuette and seven smaller ones) and laying the foundation for the future of the company. It has since been named the greatest American animation by the AFI, and earned over $130 million in re-releases.

A New Home

The success of Snow White enabled Walt to move the company to far grander headquarters.

In 1939 Disney bought a 51-acre property in Burbank, California, and began construction of the new Walt Disney Studio complex. Designed by architect Kem Weber with input from both Disney brothers, the new premises signalled Walt’s ambition and his commitment to feature films. They were built to suit the animation process, with an animation building at the centre surrounded by other departments.

By the end of the year the team had moved from Hyperion Avenue to the new headquarters, where Disney’s corporate hierarchy remains to this day.

Faltering Fortunes

Following the move to Burbank Disney ramped up production on feature length animated films.

First came Pinocchio, the adaptation of Carlo Collodi’s 19th century fairytale. Production started before the completion of Snow White, but was put on hold by Disney until problems with the story were ironed out. Though it went on to help define the studio (the Oscar-winning song ‘When You Wish Upon A Star’ is the company’s fanfare today) it lost money in its original theatrical run when released in 1940.

Next came Fantasia, Walt’s attempt to restore Mickey Mouse to the top of the Disney tree. The film grew from what is still its most famous and popular segment, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and was expanded at the suggestion of conductor Leopold Stokowski. It was technically brilliant, but not a financial success – it didn’t make a profit until its fifth re-release in 1969.

Dumb Animals

After the financial disappointments of Pinocchio and Fantasia, Dumbo was planned as an inexpensive way to turn the studio’s sour box-office run around.

It was short at 64 minutes, and featured simple watercolour backgrounds, but it was the success the studio was looking for. Costing a little over $800,000 the film made twice that in cinemas, despite a divisive animator’s strike causing a five-week delay to production.

The final film released by Disney before the war effort took full hold was 1942’s Bambi. It was originally planned as the studio’s second feature after Snow White, but adapting the dark source material and realistically animating animals proved complex and Walt put the project on hold. Efforts to overcome these obstacles included the creation of a small zoo in the studio so animators could study the movement of animals first-hand. With the world at war Bambi lost money during its initial run, but was hugely influential and, six re-releases later, has made over a quarter of a billion dollars theatrically.

Disney In The War

Following the United States’ entry into World War II in December 1941, the Disney company was increasingly tied into the war effort.

That month part of the studio itself was commandeered by the military as a repair shop housing 700 men. But soon the animation process itself was recruited, with government contracts signed to produce a series of instructional films (‘Aircraft Carrier Landing Signals’, ‘Battle Of Britain’, ‘Food Will Win The War’) and propaganda shorts like Der Fuehrer’s Face (with Donald Duck worked like a slave in the Nazi war machine) and the more serious and tragic Education For Death .

In addition, the Disney studio created over 1,200 insignia for battle units active in the Second World War , using a dedicated team of artists.

Latin Passion

With the usually lucrative European market disrupted by war, Disney looked to the potential of its American neighbours.

Nelson Rockefeller, at the time Coordinator for Latin American Affairs at the State Department, suggested Walt tour Argentina, Peru, Chile and Brazil in 1941, before agreeing to underwrite films targeted at Latin American audiences.

They were Saludos Amigos, a collection of four animated segments with some live action released in 1943, and The Three Caballeros, a less imaginative sequel released in 1945.

Looking back, these films seem out of place among the fairytales and princesses of the carefully protected Animated Classics library (they are, respectively, entries six and seven in the canon), but the war was a difficult time for the studio, which worked hard to adapt.

Post-War Recovery

As the war ended the Disney Studio was in no financial position to get back to feature filmmaking straight away.

Following the Latin movies, three more package films were released – Make Mine Music (1946), Fun And Fancy Free (1947) and Melody Time (1948). These are not bad films, but when compared to Disney’s extraordinary and groundbreaking earlier work it was clear the studio was operating in a much reduced capacity.

Signs of recovery begin with 1949’s The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad, a bundled-together adaptation of The Wind In The Willows and Sleepy Hollow. The quality was not the studio’s best, but the retelling of two classics at near feature length showed the ambition was still there.

Striking Back

The animator’s strike that hit the studio in 1941 left a lasting impression on Walt and the company.

The mood at the studio and the relationship between the animators and their managers was forever changed. And Walt himself was left convinced that unions, socialists and communists were evil and actively attempting to undermine him.

This led directly to the one of the more controversial passages in Disney history, when Walt volunteered to appear as a friendly witness in front of Joseph MacCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee , where he blamed communist infiltrators for the 1941 strikes and named several former employees as suspected communists.

Back On Track

After a few years of post-war consolidation, Disney returned with its first animated feature in eight years with 1950’s Cinderella.

In tone and style it was very similar to the company’s first film, Snow White, and despite costing a mammoth $3,000,000 was a big enough hit to get the studio up and running again.

Work restarted on two projects that had been planned before the war, Alice In Wonderland (released in 1951 and not a big success) and Peter Pan, which became the biggest grossing film of 1953.

Back On Track

After a few years of post-war consolidation, Disney returned with its first animated feature in eight years with 1950’s Cinderella.

In tone and style it was very similar to the company’s first film, Snow White, and despite costing a mammoth $3,000,000 was a big enough hit to get the studio up and running again.

Work restarted on two projects that had been planned before the war, Alice In Wonderland (released in 1951 and not a big success) and Peter Pan, which became the biggest grossing film of 1953.

Going Live

After years of producing feature length animations and combinations of animation and live action, in 1950 Disney produced its first ever full-length live action film, Treasure Island.

Filmed in London with funds frozen during the war, it was a straightforward adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson classic, with Bobby Driscoll – the voice and reference model for Peter Pan – cast as Jim Hawkins.

Driscoll had won a special Academy Award the previous year for best young actor, and his performance powered the film to international success, and kicked off a cycle of Disney-produced live action films that included The Story Of Robin Hood And His Merrie Men (1952), The Sword And The Rose (1953) and 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954).

A Wonderful View

From Snow White onwards Disney had been locked into a distribution arrangement with one of Hollywood’s original Big Five studios, RKO Pictures. Disney made the films, and RKO put them into theatres.

The successes of Cinderella and Peter Pan, and RKO’s reluctance to release Disney’s new True-Life Adventures series, led Walt and Roy to create their own distribution arm, called Buena Vista Distribution (named after the street address of the Burbank studio).

This paved the way for greater profits and a greater control over their output. The name Buena Vista is currently being phased out, but if you’ve seen a Disney film in theatres or at home, you’ve seen the Buena Vista intro sequence which has defined the studio’s films for decades.

Walt On The Box

Disney’s first steps into television came in December 1950, with a one-hour special sponsored by Coca-Cola called An Hour In Wonderland that aired on NBC.

Then in 1954 ABC signed a $500,000 deal for Disneyland, a weekly show in which Walt himself would present new and existing cartoons, and even edited versions of the company’s feature films.

It was a huge step – fledgling network ABC had its first hit, and Disney became the first major studio to enter television production. The show itself would exist in some form or another until 2008, and provided Walt with the funds to pursue his next dream.

The Magic Kingdom

The idea for Disneyland came from two sources. One, Walt’s boredom while taking his daughters to traditional theme parks, which led him to imagine a place that could entertain both adults and children. And two, his love of trains. After his doctor suggested he find a hobby to give him time away from the studio, Walt got heavily into trains (he took his backyard track so seriously he had his wife sign a contract about digging a tunnel under her flower garden).

Ollie Johston, one of the Nine Old Men, remembers Walt was on the verge of putting a railroad in the studio itself. “Then he got to thinking there wasn’t enough room and before long there was a Disneyland”.

The Stanford Research Institute was hired to scout for locations, and a 160-acre site in Anaheim, south of Los Angeles, was selected. A railroad ran around the outside of the finished park, with a typical Midwestern street in the centre leading to a recreation of Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Walt announced the existence of Disneyland on his television show, and after a year’s construction and $17 million cost, it was opened to the public on July 18th, 1955.

The Sixties Swing By

While the Walt Disney Company concentrated much of its efforts on themes parks and television (The Mickey Mouse Club, Davy Crocket and Zorro were all hits), it also continued to produce classic animated films.

At the time of its release in 1955 Lady And The Tramp – based partly on Disney veteran Joe Grant’s own Springer Spaniel – took more at the box office than any Disney animation since Snow White. 1959’s Sleeping Beauty was initially a disappointment, and led to a 30-year hiatus in animated fairytales at the studio.

101 Dalmatians followed in 1961. This was a solid success – the tenth highest-grossing film of the year – and introduced a new, time-saving Xeroxing process that replicated animators’ drawings directly onto the film cels, giving the film its sharper, sketchier look. And next there was The Sword In The Stone, a version of the Arthurian legend which became the sixth highest grossing film of 1963. It was the last animated film released while Walt Disney was alive.

A Spoolful Of Sugar

By the mid-1960s Disney was releasing more live action movies than animation features, and the studio at Burbank had been modified to accommodate live action filming (partly funded by Jack Webb, the producer and star of Dragnet, in return for studio time to shoot the series) .

The live action films included doggie tear-jerker Old Yeller, family comedy The Parent Trap, and, in 1964, Mary Poppins. This adaptation of the P.L. Travers books became a huge success, finishing the year as the overall box office number one (ahead of The Sound Of Music, Goldfinger and My Fair Lady) and earned five Oscars, including one for Julie Andrews for best performance (she beat Audrey Hepburn, who was playing Andrews’ original stage role in My Fair Lady).

The only roundly criticised element of the film was Dick Van Dyke’s wayward cockney accent. The actor’s excuse? “They got me a voice coach who was Irish. He didn’t do an accent any better than I did.”

Goodbye Walt

Walt Disney was a regular polo player and was scheduled to undergo surgery for a neck injury sustained while playing the sport in October 1966. A preliminary x-ray found a large tumour on his left lung, and despite surgery to remove the lung and chemotherapy, Disney died of a heart attack on December 15th, 1966.

Apprently the last thing Walt wrote on his deathbed was the name of then-child star Kurt Russell. Russell himself has confirmed this, but has no idea what it means. After his death his brother Roy came out of retirement to assume control of the studio.

Here’s our favourite Walt Disney quote, when asked about the merits of celebrity: “It feels fine when being a celebrity helps me get a choice reservation for a football game… As far as I can remember, being a celebrity has never helped me make a good picture, or a good shot in a polo game, or command the obedience of my daughter, or impress my wife.”

The Next Conquest

In the years before his death, Walt had been planning a second holiday resort to complement Disneyland. Through dummy corporations, the company had been buying parcels of land in Florida, through the mid-‘60s, and construction began soon after.

The resort was named in Walt’s honour – Walt Disney World – and opened to the public on October 1st, 1971. Roy said of the dedication, “Everyone has heard of Ford cars. But have they all heard of Henry Ford, who started it all? Walt Disney World is in memory of the man who started it all, so people will know his name as long as Walt Disney World is here.”

Since the opening of Disney World, several other resorts have opened worldwide, including Tokyo Disney in 1983, Disneyland Paris in 1992, and Hong Kong Disneyland in 2005, with a Shanghai Disneyland planned for opening in 2014.

So Long, Roy

Just two months after the opening of the new resort, in December 1971, Roy Disney died of a stroke.

For nearly fifty years Walt and Roy had given The Disney Company tremendous consistency of leadership, and now for the first time non-founding, non-Disney personnel would be in charge.

Donn Tatum, who had joined the company in 1956, took over along with Card Walker, who’d been a mailroom boy as early as 1938, and Walt’s son-in-law Ron Miller.

Under New Management

Under this new management the Walt Disney Company stuttered its way through the 1970s.

There was a solid run of animated output that included 1971’s charming but sub-Dalmatians adventure The Aristocats, 1973’s straightforward Robin Hood, and rodent adventure The Rescuers in 1977, which represented a coming together of old and new talents within the company and showed a touch of the old Disney heart.

On the live-action side there were successes like Escape To Witch Mountain in 1975, Freaky Friday in 1976, and, following the huge draw of Star Wars, The Black Hole in 1979. Though the box office figures were fine, there wasn’t the same creative buzz around the studio’s films, and with The Black Hole and a few other releases Disney slipped lazily into PG-rated films for the first time. The audience was shifting, and the magic was fading.

Arcade Ace

The creative slump continued and things only deteriorated as the studio entered the 1980s. To make matters worse, former long-time Disney animator Don Bluth had left the company in 1979 and was now beating it at its own game, with hits like The Secret Of NIMH, An American Tail and All Dogs Go To Heaven.

Big changes were about to alter Disney permanently, but before they took effect one standout film emerged from the stalling studio, in the shape of the computer-influenced, special effects-heavy sci-fi adventure Tron.

The film was written and directed by Steven Lisberger, who had developed the film independently and been turned down by other studios including Warners, MGM and Columbia. The resulting mix of computer animation and live-action was hugely influential – Pixar creative head John Lasseter is on record as saying “without Tron there would be no Toy Story” – although only a modest box office hit, making $33 million from a $17 million budget.

The Killer Dillers

With leadership of the company floundering Disney was vulnerable in a way it hadn’t been before. Corporate raider Saul Steinberg attempted a hostile takeover of the company in 1984, which was saved by white knight investment from Sid Bass.

In response, Bass along with Roy’s son Roy Edward Disney brought in Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had enjoyed a string of hits at Paramount, to run the studio alongside Frank Wells from Warner Bros.

At Paramount, Eisner and Katzenberg had worked under Barry Diller as part of a savvy production unit which expertly capitalised on cross-media promotions, smart high-concept pitches and music video aesthetics to put together a succession of money makers. Using two new arms of the Disney company – Touchstone and Hollywood Pictures – they would do the same at Disney.

The Magic Returns

Traditional animation and continued under Eisner and Katzenberg. The Black Cauldron was a disappointment – and the first Disney animation to earn a PG rating – but Basil The Great Mouse Detective was a hit and promised greater things to come.

The studio also began the release of its classics library on home video, beginning in 1984 with Dumbo, and returned to cartoon production for television for the first time in 30 years.

Their leadership might have been very different to Walt’s own, but Eisner and Katzenberg got things moving again. And in 1988’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit, a glorious gumshoe mystery bringing together live performance and animation (not to mention cartoon characters from Disney, Warner, MGM, Paramount, Universal and others) they had film which was innovative, technically challenging and thrilling in a way Disney movies hadn’t been for too long.

Princess Comes Home

The Great Mouse Detective was no false dawn. Under the new management the magic finally returned to Disney’s animated features.

Ron Clements and John Musker, two of four directors on The Great Mouse Detective, returned in 1989 with The Little Mermaid. It was the first Disney animation to be based on a traditional fairytale for 30 years, and was given far more resources than any of the studio’s recent animations.

Eisner and Katzenberg gambled big, and it paid off. The film was the first animation to gross over $100 million, recaptured the old Disney dazzle and paved the way for a decade of animated succeses – Aladdin, The Lion King – that could stand shoulder to shoulder with the company’s best.

Arthouse Edge

By the early 1990s Disney was back on top form, producing regular hits and earning good money from home video, television, and its theme parks.

But one increasingly profitable area in which it couldn’t compete was in the arthouse/indie market. To key into that market, Disney announced the $80 million purchase of the often controversial Miramax Films in 1993, and the services of controversial producing duo Bob and Harvey Weinstein.

Over the next 15 years Miramax would produce several non-Disney-like hits such as Clerks, Pulp Fiction and Trainspotting, as well as Oscar-bait quality films such as The English Patient and Shakespeare In Love. Through Miramax’s horror label Dimension, Disney also released the Scream trilogy, The Faculty and Mimic.

Brand New Toy

Just as Disney’s traditional animation was beginning to enjoy renewed success, a new development emerged which would render it almost obsolete.

The history of Pixar – the computer graphics company turned next generation animation studio – is intertwined with Disney’s. Pixar’s driving creative force, John Lasseter, was once an animator at Disney, and during the production of The Little Mermaid the old studio had experimented with Pixar’s new CAPS system to speed up animation.

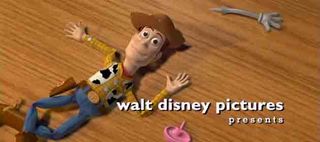

In the early ‘90s, when Pixar had reached the stage where it was ready to contemplate a large animation project, Katzenberg offered the company a three-picture deal. And after a production that rewrote the rules of animation just as Walt Disney had done with sound, Technicolor and several other advances, Toy Story heralded the future of the industry when it was released on November 22nd, 1995, racking up $361 million in cinemas and tellingly out-grossing Disney’s own animation Pocahontas by $15 million.

Executive Split

Jeffrey Katzenberg wasn’t around at Disney to celebrate Toy Story’s success. He left Disney in 1994 following the death of Frank Wells, after which Eisner refused to promote him to the vacant position of president.

Instead Katzenberg went on to form Dreamworks with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen. The new studio made a run of Miramax-troubling artistic hits like American Beauty, Gladiator and A Beautiful Mind, and more significantly Katzenberg established an animation department that would provide a serious challenge to Disney and Pixar’s box office dominance, with films like Shrek, Madagascar and How To Train Your Dragon. Eisner had created his own worst enemy.

His replacement of Katzenberg went badly too. In October 1995 Michael Ovitz, the one-time ‘super agent’ and friend of Eisner’s, became president of Disney. His tenure was disastrous and he was eventually fired in 1997 with a severance package worth over $150 million.

Mergers And Acquisitions

Aside from this executive kerfuffle, Disney’s continued success led naturally to a period of expansion and acquisition.

Aside from Miramax, Disney made other significant buys. In 1996 the company paid $19 billion for ABC, the television network which had first aired Disney’s anthology series and where Eisner had worked for a decade before joining Paramount. This included an 80% stake in sports network ESPN.

In 2001 a $3 billion deal was made for the Fox Family Network, giving Disney access to a cable network reaching 81 million homes, and then in 2009 Disney bought Marvel Entertainment and its huge library of characters and storylines.

Eisner Out

Despite this rapid growth, by the turn of the millennium Disney was slowing down once again.

The decade of Disney renaissance signalled by The Little Mermaid had come to an end, and a string of tired, empty disappointments had started (The Emperor’s New Groove, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, Treasure Planet, Brother Bear, Home On The Range).

In 2003 Roy E. Disney resigned as the company’s vice-chairman to lead a campaign that reflected growing shareholder dissatisfaction with Michael Eisner, accusing the CEO of turning Disney into a “rapacious soul-less” company. Eisner announced he would be stepping down in September 2005.

Meet The Future

The success of Pixar was a boost to Disney, as the distributor split box office profits with the production company but held on to revenues from toys and merchandising. Disney made more money from Pixar's hits than Pixar did.

But with a faultless box office track record Pixar was naturally keen to renegotiate the terms of its deal with Disney, and soon a deadlock seemed likely. In light of this, Disney’s ability to create their own artistically applauded and profitable computer animated films took on an extra significance.

The studio’s first attempt was Chicken Little, which cost a sizeable $150 million but also took in over $300 million. It was not a tearaway success – and the film itself is flat – but it showed the studio was not totally reliant on Pixar, and paved the way for the later CG hits Meet The Robinsons and Bolt.

The Right Guy

Eisner’s replacement Robert Iger swiftly patched things up with both Roy E. Disney and the company’s disgruntled shareholders, as well as Pixar.

In fact, Iger had a much bigger idea than simply renegotiating the distribution deal with Pixar. Desperate to return Disney to the glory days of animation, he realised to do that he needed the right people, and that “Pixar had more of the right people than probably any other place in the world.”

So it was that Disney announced on 24th January 2006 it had purchased Pixar for $7.4 billion and – crucially – installed Toy Story director John Lasseter as chief creative officer of both Pixar and Disney’s animation studios. Since the death of Walt Disney the company has lacked a controlling creative mind with a love of animation-as-art and a hunger for the possibilities of technology. Lasseter fits the bill nicely.

A Tangled Look Ahead

In 2004 Eisner had publicly stated that Disney was done with hand-drawn animation for good. Under Lasseter, an old Disney animator with a respect for the craft’s traditions, that position changed.

2008’s The Princess And The Frog became Disney’s 49th animated feature film, and the first to resurrect hand-drawn animation. It was a solid box-office performer, and had more stylistic substance than the last ten years of Disney output combined.

And now there is Tangled, another Disney princess tale that continues the studio’s growing success with CG films. It’s already made a huge $400 million at the box office, and it’s released in the UK on the 28th January.