The Story Behind Star Wars

A long time ago, in a studio far, far away...

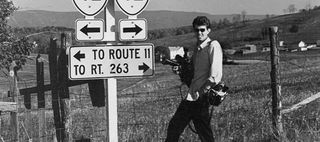

Curious George

Star Wars starts with George Lucas, the boy from Modesto (the nearest thing they have to Tatooine in California) who grew up to be the bearded billionaire king of blockbusters.

Born in May 1944 to a stationary store-owning father, George grew up watching Buck Rogers serials and racing cars. He studied anthropology at college (“How society works, how people put themselves together and make things work, has always been a big interest. [It’s] where mythology comes from, where religion comes from”) before heading off to USC to enrol in the university’s new film course.

Here a burgeoning interest in cinema – Lucas would drive to San Francisco to watch avant garde shows – became a full-time obsession. He soaked up the works of masters like Kurosawa and Godard, and began to make his own films – shorts at first, then documentaries which eventually landed him on the set of The Rain People, directed by a young screenwriter/director called Francis Coppola.

American Zoetrope

At the time these young filmmakers met – as the sixties became the seventies –established Hollywood was breaking apart, the dissembled studio system finally giving way.

There were new opportunities. “You could just waltz in and have these meetings and propose whatever,” remembers Paul Schrader, writer of Taxi Driver.

Lucas and the visionary Coppola were hip and full of a creativity the studios were desperate for after the success of Easy Rider. The pair took advantage, establishing independent studio American Zoetrope and beginning to make movies – beginning with THX 1138, a clinical feature version of Lucas’ student film.

"Something commercial..."

The cold, ultra-styled THX 1138 bombed so hard it almost destroyed Zoetrope before it had started. Lucas and Coppola’s deal with Warner Bros was cancelled (and with it Lucas’ early version of Apocalypse Now) and the boys needed to make good quick or go bust.

“They said ‘This is all junk, you have to pay us back the money you owe us’” remembers Lucas of the Warners deal. “Which is why Francis did Godfather. He was so much in debt he didn’t have any choice.”

Lucas was in a similar boat, and decided to push on with his semi-autobiographical rock ‘n roll movie, American Graffiti. Initially set up at United Artists, the movie switched to Universal when UA became nervous about the cost of the licensed soundtrack. It was worth the risk – the film went on to make $55 million on its initial run.

The Star Wars

Cruising and cars wasn’t the only commercial project that Lucas dreamt up. Alongside American Graffiti he’d also visualised what he called “a Western movie set in space.”

“In the process of going through film school you end up with a little stack of ideas for great movies that you’d love to make, and I picked one off and said, ‘This space epic is the one I want to do.’”

Initially Lucas considered doing the film as a remake. “I remember having lunch with George at the Palm restaurant in New York,” Coppola remembered, “and he was very depressed because he had just come back and they wouldn’t sell him [the rights to] Flash Gordon. And he says, ‘Well, I’ll just invent my own.’” The title ‘The Star Wars’ was registered with the MPAA in August 1971.

Writing The Opera

In 1973 Lucas sat down to begin his space opera, but the writing didn’t come easy. “I’m not a good writer,” he admits. “It’s very, very hard for me. I don’t feel I have a natural talent for it—as opposed to camera, which I could always just do.”

A now infamous round of treatments and drafts began, initially under the title Journal Of The Whills and with this ungainly opening line: “This is the story of Mace Windy, a revered Jedi-Bendu of Opuchi, as related to us by C.J. Thorpe, padawaan learner to the famed Jedi.”

Thankfully much drafting ensued, with Lucas leaning heavily on the plot of Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress to formulate a story of knights, wizards, princesses and evil empires which brought together myths of America’s West with the action and spectacle of Lucas’ childhood sci-fi serials.

A Galactical Deal

Lucas was contractually obliged to offer Star Wars first to United Artists, who passed, and then to Universal. This was just as American Graffiti was gearing for release and a nervous Universal was demanding cuts and rowing with the director. He was relieved to see them pass too.

Alan Ladd Jr., the head of creative affairs at Twentieth Century Fox, had seen a smuggled print of American Graffiti and believed in Lucas. “When he said, ‘This sequence is going to be like The Sea Hawk or this like Captain Blood or this like Flash Gordon,’ I knew exactly what he was saying,” the producer said.

Lucas signed a $150,000 deal to write and direct, plus – the crucial bit – retained full rights over Star Wars merchandising and sequels. Three weeks later American Graffiti became a huge hit and Lucas became a millionaire thanks to his share of revenues. He started to build his film empire - meanwhile, Star Wars was ready to roll.

Young Stars

Lucas ran casting sessions alongside his friend Brian De Palma, who was preparing his Stephen King adaptation Carrie. Several of the actors, including Sissy Spacek and Carrie Fisher, auditioned for both movies.

The actors were tried out as groups to test their chemistry, with Lucas keen on using young unknowns against the studio’s wishes.

Eventual star Harrison Ford, who had appeared in American Graffiti and Coppola’s The Conversation, was helping at these group sessions when Lucas decided to cast him ahead of other hopefuls such as Kurt Russell, Nick Nolte, Christopher Walken and Sylvester Stallone as charismatic space pirate Han Solo.

Old Troopers

Balancing out the youth of the central cast, Lucas also hired several experienced English performers, key among them Hammer veteran Peter Cushing and Ealing great Alec Guinness.

Cushing was never precious about his profession, and said of his role as Grand Moff Tarkin “My criterion for accepting a role isn't based on what I would like to do. I try to consider what the audience would like to see me do, and I thought kids would adore Star Wars.”

Although Guinness would famously grow tired of the Star Wars circus, at the time he was also positive about the film, and Lucas. “In many ways he is quite untypical of the film industry,” Guinness noted. “When we started work it was all so calm, so gentlemanly. I remember someone on the set criticising Lucas because of his lack of display and announcing that the film was going to be dull. So I took him to aside and said ‘Mark my words, this film is going to have distinction .’

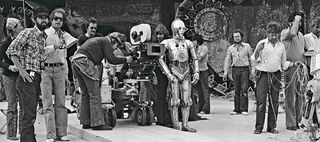

The Production

The shoot itself began in June 1976, and was far from smooth. The film fell behind schedule on location in Tunisia, thanks to storms and unexpected Libyan interest in the Jawa Sandcrawler. “It's true about the border,” Lucas said at the time. “They had to come and inspect the Sandcrawler to verify that it was not a secret weapon.”

When the production then moved to Elstree Studios outside London Lucas often clashed with the British crew, and eventually ran two weeks late. Faced with increasing studio pressure, Lucas was diagnosed with hypertension.

There was scant comfort from the cast, who were less than impressed with the script. “We’d come into a scene and we’re faced with dialogue straight from Buck Rogers” Harrison Ford told a radio show after filming had wrapped. “I mean, I used to threaten George with tying him up and making him repeat his own dialogue.”

The Costumes

While the writing might have been questionable, Star Wars’ special effects and production design were truly class-leading. Not that the actors necessarily appreciated their costumes.

“The whole first film was a miasma of pain” says Anthony Daniels of his C-3PO outfit. “It was the metal pieces of the suit shoving me about, meeting with another piece of metal to pinch me horribly. It was like sticking your fingers in an electric socket, again and again.”

Fisher didn’t much care for her princess get-up, either. “I had to wear that white dress and I couldn't wear a bra,” she remembers. “Everything was bouncing around, so I had to wear gaffer's tape for three months to keep my breasts down. A new crew member used to come up every day and get to rip it off. Only kidding!”

Making Magic

Finding that Fox’s own visual effects department had closed, Lucas established his own and called it Industrial Light & Magic. ILM would go on to be the most influential visual effects company in the blockbuster era.

Initially Lucas approached Silent Running director Douglas Trumbull for help – Trumbull suggested John Dykstra, who helped the director assemble the initial ILM team and developed the Dysktralfex motion picture camera system used for Star Wars’ miniature effects shots.

Initially work progressed painfully slowly. Half the budget was reportedly spent on four shots which Lucas thought were unusable, and it was only by cramming a year’s worth of production into six months that deadlines were finally met.

The Cut

The film’s original editor, John Jympson, turned in a first cut that Lucas regarded as a “complete disaster.” Unable to convince Jympson to reshape the film as he desired, Lucas needed to replace him.

Enter Lucas’ own wife, the often under-credited Marcia Lucas. Marcia had played a large role in George’s success – working steadily and paying the bills during his early films – and was a central figure in the wider New Cinema movement.

“She was a stunning editor” says John Milius. “She’d come in and look at the films we’d made and she’d say, ‘Take this scene and move it over here,’ and it worked. She did that to everybody’s films: to George’s, to Steven’s, to mine, and Scorsese in particular.” Her work on Star Wars would win her an Academy award.

The Merchandise

In time Lucas would make his fortune from, and Star Wars would become known for its extensive merchandising lines. Before the days when Happy Meal tie-ins were the norm, the young stars found it amusing.

“Harrison used to get so upset” Fisher giggled at the time. “‘Mark gets to be a puzzle, why don't I?!' Those kinds of arguments. I mean, if I'm gonna end up being two sizes of dolls, and a belt, and a cookie, and a hat, then why don't I get to be on an eraser, too?”

“I've been marked down in price,” Hamill said to a Rolling Stone interviewer. “My wife and I went into a Toys 'R Us store a while back, and they had all these kids' costumes. They had sold out Darth Vader, Chewbacca and C-3PO, and I was the only one available. There were just boxes and boxes of me.”

The Release

A famous early viewing of the film’s rough cut for Lucas’ friends – including Coppola, De Palma and Milius – drew disappointingly mixed reactions. But Spielberg, along with the Fox executives, were certain they had a hit.

They were right. The film was released on May 25th 1977 and, primed by a clever marketing campaign spearheaded by Lucasfilm itself (including crossover deals for a Marvel comic and a novelisation) was an enormous hit, overtaking Spielberg’s Jaws as the biggest grossing movie to date and eventually making over $700 million.

The film would also have an eventful afterlife, with re-releases on home video and in theatres including various tweaks and digital additions undertaken by Lucas himself including, if rumours are true, some new edits for the upcoming Blu-ray...

Star Wars: The Complete Saga is out on Blu-ray on 12 September.

Andor showrunner hopes that the Disney Plus show's success helps convince Lucasfilm to sign off on either a Star Wars horror movie or sitcom

Black Mirror's USS Callister team says surprise sequel episode in season 7 is less '60s Star Trek and more big-screen Star Wars: "It feels a bit Return of the Jedi"

Andor showrunner hopes that the Disney Plus show's success helps convince Lucasfilm to sign off on either a Star Wars horror movie or sitcom

Black Mirror's USS Callister team says surprise sequel episode in season 7 is less '60s Star Trek and more big-screen Star Wars: "It feels a bit Return of the Jedi"