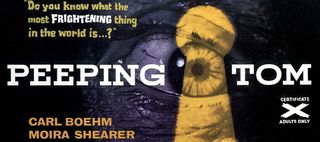

The Story Behind Peeping Tom

Seminal Brit thriller celebrates 50th anniversary

Learning to love the psycho

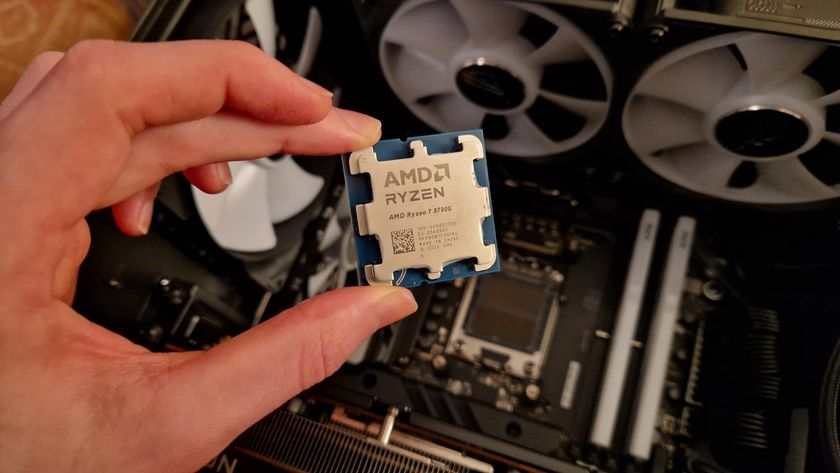

This week, Michael Powell's renowned thriller Peeping Tom celebrates its 50th birthday. The celebrations include a newly restored print hitting cinemas on November 19th, before the film makes its Blu-ray bow on November 22nd.

Given the critical attention that's now lavished on Peeping Tom , it's hard to believe that the movie suffered such a diabolical reception in 1960. Critically lambasted, the film's performance was seen as a large factor in the downward spiral of Powell's career. Indeed, he struggled to work in Britain again, and ended up seeking work elsewhere.

How did one little movie cause such a stir? Could Peeping Tom (and the critically kicking it inspired) really have been the death knell of one of Britain's finest movie makers?

Like its close sibling Psycho , one of the most remarkable things about Peeping Tom is its enduring power; it retains the ability to shock and impress, and feels fresh despite the fact it is five decades old. So why did Psycho (admittedly a Hollywood flick with a Brit director) succeed where Peeping Tom failed?

While the movie's reception must have been devastating for Powell, one can't help but think that perhaps he was still able to retain some perspective on the film's qualities. In an interview given after the release of Peeping Tom , Powell said of his audience: "The English will always laugh at themselves eventually, even if it's not until 10 years after the event."

Though, perhaps in retrospect, 10 years was a bit of an underestimation.

Pre-Tom Powell

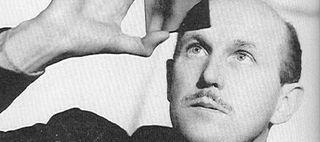

It's impossible to consider Michael Powell, and his directorial work before Peeping Tom , without thinking about Emeric Pressburger.

Hungarian Pressburger came to Paris (in 1933), and later to London (in 1935) to escape the rise of the Nazis. His career path took him from journalist to screenwriter to movie producer. He first worked with Powell in 1939 on WW1 thriller The Spy in Black , which starred Conrad Veidt as a German submarine commander, and it was the start of a partnership that would go on to define British filmmaking for the next 20 years.

Known collectively as The Archers, the pair produced a string of critical and commercial successes, including The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp , A Canterbury Tale , A Matter of Life and Death , Black Narcissus , and The Red Shoes .

A duo in the truest sense, both men take credit for writing, directing and producing these pictures, though it is widely acknowledged that Powell acted as the director, while Pressburger held more sway in producing and screenwriting.

Powell himself claimed: "I'm a director; I hate writing." The distinction between the pair's work is fairly seamless though. Acting as producers of their own work allowed them to retain a great deal of control over their films.

On a scale of British directors of their era, The Archers output is only rivalled by the likes of Hitchcock and David Lean, in terms of breadth and consistency of quality.

But Pressburger would not be involved with the making of Peeping Tom .

The making of the movie

After a string of underwhelming collaborations, Powell and Pressburger decided to go their own separate ways. There was no love lost between the pair, who remained firm friends for the remainder of their lives. They would even join forces again for a couple of collaborations ( They're a Weird Mob and The Boy Who Turned Yellow ), though they failed to scale the dizzying heights of their previous successes.

Powell's first movie made after the separation of The Archers was Honeymoon , in which a just-married couple travel Spain. The dance-filled movie failed to match the impact of The Red Shoes , and Powell moved on to his next project, Peeping Tom .

The script came from Leo Marks, a cryptographer and playwright. Incidentally, Peeping Tom champion Martin Scorsese would later hire Marks to do uncredited voicework in The Last Temptation of Christ .

Something in Marks' screenplay clearly resonated with Powell, a director who had never made and out-and-out horror before, though similar themes could be found in his previous films: the suffocating hysteria of Black Narcissus , the art addiction subtext in The Red Shoes .

But Peeping Tom is far from a 'generic' horror. Powell said on the subject: "I don't think of it as a horror film at all - I tried to go beyond the ordinary horror film of unexplained monster, and instead show why one human being should behave in this extraordinary way - it's a story of a human being first and foremost."

A very British psycho

Perhaps it was the normality of the protagonist that caused such a frenzied mauling of the movie on its release.

Sure, Mark Lewis, portrayed by Carl Boehm, is a terrifying screen icon, but much like his stablemate Norman Bates, there's something altogether normal about him. Both 1960 psychos share a great deal more in common. For starters, there's the overbearing parents that both have (although Tom 's father and Psycho 's mother take things off on altogether different Freudian tangents).

Then there's their awkward relationships with women, and their dwellings, which seem to define them: multi-layered spaces that literally and metaphorically represent so much, taking in guests, and playing a vital role in establishing the shifting power dynamics.

There's something extremely vulnerable about both characters, an uncomfortable proposition for an audience watching a movie about a serial killer. It's the everyman quality of these psychos that makes them so compelling, but the casting of handsome actors in the roles went against the grain of what was expected.

Powell lined himself up for even more criticism by playing Lewis' psychologist father in the old footage that the killer obsesses over. Having his young son play the infant Lewis made matters even more controversial, though Powell argued that his son enjoyed the experience, and claimed that using a family member helped him to get a more naturalistic performance from the youngster.

Unfortunately, Peeping Tom wouldn't hang around long enough to give audiences a chance to immerse themselves into its complexity.

The critical backlash

The drubbing that Peeping Tom received is among the most famous in movie criticism history. The fact that the slaying marked the beginning of the end of Powell's career is a testament to the widespread extent and vitriolic intensity of the general consensus.

Critic Caroline Lejeune reportedly walked out of the press screening exclaiming "I'm sickened", without even sticking around for the rest of movie. Len Mosley, writing in the Daily Express called the movie a "nasty little epic". The Daily Worker's review was entitled 'Ugh!' and claimed that: "From it's slumbering, mildly salacious beginning to its appallingly masochistic and depraved climax, it is wholly evil."

Perhaps the most famous slam came from The Tribune. Critic Derek Hill wrote that "The only really satisfactory way to dispose of Peeping Tom would be to shovel it up and flush it swiftly down the nearest sewer. Even then the stench would remain."

As well as tarnishing Powell's reputations, the repulsion evident in the reviews often seems to go right to the heart of the reason why Peeping Tom had such a huge impact, and frequently hints at the same ideas that would be used by critics to sing the movie's praises in decades to come.

For example, in The Star, Ivor Adams called it "a film which, despite its technical skill, nauseated me… why, oh why, use such skill with such negative results?" Not only does it sing the praises of Powell as a filmmaker, but it hints at the challenging, uncompromisingly voyeuristic aspects of the film, that left (and still leave) audiences so uncomfortable.

Cinema and voyeurism

It's the uncomfortable analysis of filmmaking as voyeurism (and the implication of the spectator in that act) that has allowed Peeping Tom to remain such a talked about and interesting movie.

In the book Scorsese on Scorsese , the Taxi Driver director is famously quoted as saying "I have always felt that Peeping Tom and [Fellini's] 8½ say everything that can be said about film-making, about the process of dealing with film, the objectivity and subjectivity of it and the confusion between the two. 8½ captures the glamour and enjoyment of film-making, while Peeping Tom shows the aggression of it, how the camera violates…"

Under the guise of a psychological horror, Powell makes pointed and acerbic observations about the very art of filmmaking. The camera itself feels like one of the most important characters in the movie.

Lewis's weapon of choice has a sharpened tripod leg that he uses to impale his victims. There's also a mirror attached to the device so that the victims are forced to watch themselves as they die. Lewis' motive throughout is to create a documentary on the topic of fear, and he plans to make the final appearance himself.

As well as Lewis' role as the 'killer' director, Powell implicates the audience from the offset, with a powerful opening: the camera's POV follows Lewis as he kills as prostitute. After the act has taken place, we seamlessly witness Lewis watching the film projected in his hideout.

Roger Ebert wrote: "Why did critics and the public hate it so? I think because it didn't allow the audience to lurk anonymously in the dark, but implicated us in the voyeurism of the title character."

Perhaps those critics were right to feel uncomfortable.

A funny thing

In the years since Peeping Tom 's release, much has (gradually) been made of the humour within the film.

Yes there's a great deal of darkness, self-reflection and film-making subtext, but it's also blackly funny, with Powell likely to have you cackling nervously in the darkened auditorium. The humour varies from Lewis' sly comment that he's from 'The Observer', to the presentation of the almost-parodic movie mogul character Don Jarvis ("The silly bitch has fainted in the wrong scene!").

The movie is ingrained in the cinema: Lewis is a lowly crew member who aspires to rise through the ranks, and in his spare time he shoots photos of glamour girls. Peter Keough describes the darkly funny scene in which Vivian's (Moira Shearer, star of The Red Shoes ) body is discovered in a trunk on the film set as "a scene of ruefully funny, self-reflexive black comedy."

There's a number of references to the 'danger' of filmmaking throughout, as Powell lays himself bare in the flick: the director once claimed "I think the camera is very frightening."

There's something funny, and at the same time extremely disturbing, about the way in which all of Lewis' most frightening moments have been cinematic. His father's experiments capture Lewis' entire range of fears on film, from the shock of seeing a lizard on his bed, to the deathbed mourning of his mother.

That the director himself stars as the overbearing father in these scenes makes the irony all the more devilish.

Powell's production values

For a film that was dismissed as grotty, tawdry and cheap, the production values are classic Powell, and may come as a surprise to any viewer's for whom the movie is preceded by its reputation.

Indeed, many of the negative reviews were still keen to point out Powell's technical virtuosity.

The film is shot in gloriously rich Technicolour, with the pretty pictures only helping to make the movie all the more involving (making it harder from any viewers to shirk away from the movie's message).

Legendary lenser Otto Heller was behind the cinematography for the movie. Having previously worked on a number of Ealing movies, including The Ladykillers . The look of the film is enough to assuage any doubt that this is base trash.

Malcolm Cooke's sound design is equally able to haunt and engage at the same time, and the same can be said for the eerie piano that accompanies the movies.

These aspects of the movie weren't able to gain it recognition in its own time, though.

The fallout

While Peeping Tom is now considered Michael Powell's last great film, and a masterpiece in its own right, it signalled the end of his career in Britain.

Perhaps the critical backlash can't be blamed entirely for the failure of a film. There's still word-of-mouth, Powell's estimable reputation, and the thrill of seeing a controversial movie.

Evening Standard Critic Alexander Walker (one of the few to maintain his original, negative position on Peeping Tom decades later), claimed in a retrospective piece that Nat Cohen, the movie's producer-distributor pulled the movie under mounting pressure from the Wardour Street big boys.

Walker claims that after the film's release an industry bigwig told him: "We've stood Nat in the corner, till he junks that bit of porn." Apparently Cohen was all to keen to wash his hands of the scandalous material.

In the years following Peeping Tom , Powell never had another hit, and eventually went to Australia seeking work.

There is a silver lining to the tale though, with the disastrous reception unable to put an end to the movie. Scorsese was a longtime fan of Powell's work, and he was impressed when he watched a friend's copy of Peeping Tom .

In 1978, Scorsese put up the funds to have Peeping Tom screened at the New York Film Festival, and gradually the movie discovered cult success, which eventually led to critical acclaim.

50 years on

Scorsese remains Peeping Tom 's most famous and committed champion. He recorded an introduction for the special edition DVD release in 2007, and he recently appeared at a BAFTA event in London, celebrating the movie's half-century.

In a recent, exhaustive Total Film poll, which collected the opinions of horror icons and experts, Peeping Tom came in at no. 22 on the list. As well as that heady accolade, the film has numerous famous fans, from Francis Ford Coppola, to Edgar Wright, to Quentin Tarantino.

Chris Rodley's documentary, A Very British Psycho , is an extremely valuable and interesting watch for anyone seeking insight into the making of the movie, and its disastrous reception. The doc was made to air on Channel 4 ahead of a broadcast of Peeping Tom , but it has since been available as a bonus feature on various DVD releases.

If you've never seen Peeping Tom , now's the time to do it, with cinema and Blu-ray releases imminent. Even if you've already seen it, the restored print makes a repeat viewing almost essential, and it provides the ideal opportunity for getting retangled in the movies many layers, particularly if you can watch it on the big screen, from the hush of a darkened auditorium…

The Total Film team are made up of the finest minds in all of film journalism. They are: Editor Jane Crowther, Deputy Editor Matt Maytum, Reviews Ed Matthew Leyland, News Editor Jordan Farley, and Online Editor Emily Murray. Expect exclusive news, reviews, features, and more from the team behind the smarter movie magazine.