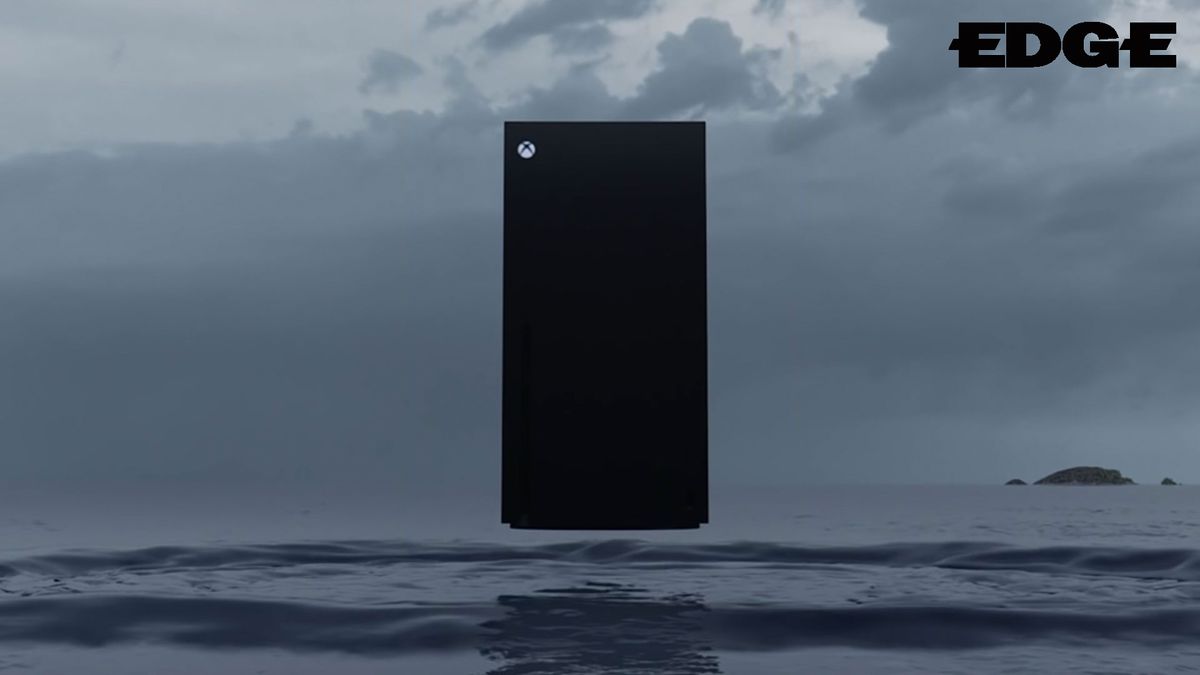

The state of next-gen: Examining the battlegrounds on which the PS5 and Xbox Series X will fight

With a new round of consoles drawing near, Edge examines the battlegrounds on which the next generation will fight

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

Three months in to 2020 and news of the next generation of consoles is tantalisingly thin on the ground. By this time of year in 2013, we'd already had our first look at PS4; as we write this, at least, Sony is still saying nothing of substance about PS5, and it appears nothing is imminent (though rumours of an imminent Wired cover continue to circulate). Microsoft is similarly keeping its powder dry until, current betting suggests, a little closer to E3.

Both companies are getting much better at keeping secrets – the bulk of the developers with whom we've had quiet words of late are also in the dark – and there's an element of brinksmanship at play, each side wary of giving the other an advantage by showing its hand first.

One of the defining moments of the battle for hearts, minds and wallets ahead of the launch of Xbox One and PS4 was Microsoft's botched handling of the used-game issue. In the run-up to the console's proper unveiling, rumours had swirled that Xbox One games would be single-use, shutting down the secondhand market – great for publishers who had spent the era increasingly fretful about the roaring trade in preowned games, but terrible for punters.

Sony's response at E3 the following month was an instant classic: a video explainer on how PS4 would handle used titles in which Shuhei Yoshida simply passed a game box to Adam Boyes. Microsoft had given its great rival an open goal, and it buried the shot.

The months ahead

No doubt both platform holders have that moment in mind as they assemble their marketing schedules for the coming year. Which makes it all the more baffling that Microsoft has, once again, left its goalposts unattended. Matt Booty, freshly minted head of Xbox Game Studios, told MCV in January that there would be no Series X exclusives during its first year on shelves.

At least the reasoning this time around is more consumer-friendly: the official line is that Microsoft doesn't want anyone buying into the Xbox ecosystem now to find their purchase obsolete when Xbox Series X arrives. But it once again means that the buildup to the launch of a new Xbox is being hamstrung by uncomfortable, and in some ways unnecessary, questions.

The Xbox division has a curious sort of form for this sort of thing – announcing a new product then swiftly giving you one less reason to buy it. At E3 in 2016, it unveiled the slimmed-down Xbox One S redesign at the start of its conference, and ended it by announcing the far more powerful Project Scorpio, which would later become Xbox One X. Project Scarlett's hype campaign was later compromised by airily vague talk about XCloud.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

At least this time around it's getting the bad news out of the way early doors. For all the nobility of Microsoft's intentions, you have to question the wisdom of how it chooses to talk about them. That is far from the only awkward question that the coming generation poses, however, and while we wait for concrete details to emerge, now seems as good a time as any to chew them over.

"With no exclusive games, Microsoft will have to be creative in how it pitches Series X to consumers."

For all that the terms of engagement have changed since the launch of PS4 and Xbox One, the absence of any true Series X exclusives will make the console a very difficult sell for Microsoft. The hypothetical video game enthusiast, who currently owns a PS4 Pro and Xbox One and only has the budget for one new console this year, simply has no decision to make.

Everything available on Series X this winter will be playable on a 4K-ready console that already sits under their TV, while PS5 will launch with exclusive games built from the ground up around its processing power and feature set. Rare indeed is the new console that launches with a good old-fashioned 'killer app'. Launching one without any exclusive games at all is simply unprecedented. It means Microsoft will have to be creative in how it pitches Series X to consumers. It is, at least, something in which it has plenty of experience; it's spent most of this generation doing it.

The announcement of backwards compatibility at E3 2015 was the turning point Xbox One – the moment at which Microsoft began to claw back goodwill after the console's disastrous start. Central to the feature's appeal is that it is doesn't cost the user a penny: the box of old 360 or original Xbox games up in the loft is now playable on the latest machine. Microsoft's greatest challenge when it comes to Series X is making backwards compatibility alluring enough to be a hefty purchase incentive.

Courting early adopters

Certainly plenty of early adopters will be interested in backwards compatibility. How Series X handles the biggest live- service games will, therefore, be critical. Yes, you'll be able to log in to Fortnite, GTA Online, or Minecraft on Series X launch day. But will they look, or feel, different enough to justify the expense? Such has the landscape shifted over the course of the current generation that Microsoft doesn't just need to court developers to fill its new box with new games, but to ensure their old ones are brought up to snuff too.

This in itself presents a problem. No doubt Series X could run Destiny 2, say, at 60fps. But given Bungie's nervousness about letting PC and console owners play together, how would it feel about players on the 30fps Xbox One line finding themselves matched against others running the game at twice the refresh rate? This is not just a Microsoft problem: Sony, so the rumour mill has it, is to offer backwards compatibility with the current generation on PS5. But it can at least distract would-be moaners with a shiny exclusive or two.

Less of a problem for launch, but potentially more of a concern in the long term, is Game Pass. The all-you-can-eat Xbox subscription service has been one of this generation's great innovations, raising the bar to such an extent it's hard to see any rival platform holder matching it. That in itself is instructive. Clearly the higher-ups at Microsoft have seen the rapid rise of Netflix, and decided that making its video game equivalent should be the Xbox division's top priority.

The most exciting thing about the PS5 is the stuff you won't even notice

So many of the decisions Microsoft has made since Game Pass' launch have fed into it: the rush of studio acquisitions to ensure the content pipeline is well stocked, the big-money deals to get new or new enough third-party games onto the service, even the way new hardware unveilings are always followed by the announcement of the next one. Wherever you go, your library will follow. Microsoft, like Netflix, wants to get you in its ecosystem, and keep you there.

Lovely stuff, providing you're prepared to overlook the extent to which Netflix's entire operating model is built on debt. By the end of September 2019, it owed over $12 billion, and told investors it would continue to borrow to fund more content development – something which has grown ever more important in an increasingly crowded space that Netflix once had all to itself. Netflix may have been the most valuable US stock of the 2010s, with growth of over 3,000 per cent over the course of the decade. But it's an empire built on sand, and its first quarterly drop in US subscriber numbers last year prompted stock to fall more than ten per cent.

Yes, Microsoft's exposure is relatively limited; it has plenty more revenue streams than just Game Pass. But the Xbox division is staking an awful lot on it, and none of its endeavours will have come cheap. The offering to consumers is outrageously generous, particularly if you take advantage of the ongoing deal that lets you convert up to three years' worth of Xbox Live membership into Game Pass Ultimate for £1 (a loophole, supposedly, that Microsoft is yet to close, months after it was discovered).

Pricing in new initiatives

The terms offered to developers are hard to resist, too, though we're told that a recent revision of the standard Game Pass deal tilted the balance back in Microsoft's favour a little. But if both players and developers are being made offers they can't refuse, presumably it's the one making them that's taking the financial hit – and you have to wonder what happens when Microsoft, or the investment community, decides that needs to change. Upset that parlous balance by giving creators or consumers a worse deal, and your service risks toppling quickly.

No doubt Microsoft has priced all this in. And it has the unique advantage of having spent the Xbox One era firmly in second place; few would dispute that it seems well placed to turn things around. Sony's problems are different, and relate more to what's been going on at the firm behind the scenes. There's been so much shuffling of the corporate deck since PS4 arrived – Jack Tretton, Andrew House, Shawn Layden and John Kodera have all rotated in and out of big boardroom chairs over the generation, while Shuhei Yoshida has left the job of running the Worldwide Studios group to Hermen Hulst, and will instead look after indies – that it's hard, currently, to get too much of a sense of how things are going to go.

Certainly, the company's conduct has given cause for concern, chief among it the hubristic abandonment of E3 and a sweeping round of redundancies among back-office staff. Until it shows its hand, however, we have no choice but to postpone judgement.

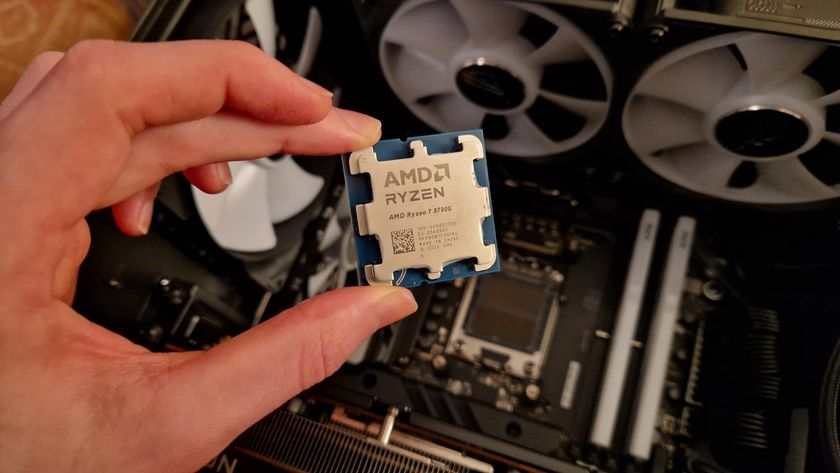

The jury is out in other respects, too. While the peaks of Sony's first party PS4 output have been stellar, there have been just as many misses. And in the latter part of the generation there's been a whiff of a template to Sony's internal exclusives: long, singleplayer, cinematic adventures in big open worlds. In that context, shuffling Yoshida offstage makes a certain sense, but given that his replacement steered Guerrilla through the development of Horizon Zero Dawn – a long, singleplayer, cinematic, you get the idea – you can't help but wonder how much appetite for change there really is. That Mark Cerny chose to show off the effect PS5's onboard SSD will have on data streaming by showing a sped-up version of Marvel's Spider-Man does not seem much of a harbinger of change.

And it is also playing catch-up in terms of services. It seems an awfully long time ago that we thought Sony had stolen a march on the cloud- gaming boom with the well- timed (and, at $380 million or so, attractively priced) acquisition of Gaikai. Almost eight years later, though, Sony has precious little to show for it. The PlayStation Now service is quite plainly operated by a company that would greatly prefer to sell you something for £50 than let you borrow it for a tenner a month. While improvements to price and software catalogue have arrived, they've been half-hearted and often temporary, and much remains to be done if it is to see off the threat of Game Pass and xCloud. Microsoft, a software company at heart, would dearly love for the coming generation to be decided by services. Sony appears to be banking on the opposite.

The history of the game industry is a pendulum, the loser of one generation getting its house in order to perform better in the next while the winner fiddles around, high on its own success. This one may well be the same when all is said and done, but there are so many new variables – of support and services, of people and their priorities – that, sat in the dark as we are, it's thrillingly hard to see how it will all pan out. One thing's for sure, though: it's going to make for absolutely fascinating viewing.

Check out the big new games of 2020 on the way this year, or watch the video below for a guide to GamesRadar's favourite games of the past decade.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.