Best Shots review: If you haven't read The Sandman, you should be losing sleep over it

The Sandman worms into your consciousness and demands regular rereads

A jaded Wednesday warrior in November 1989 searches the racks for something new. A lonely teenager checks out a battered and laminated trade paperback from the library. A curious new convert downloads the most prominent option on comiXology, spurred into action by news of an incoming Netflix adaptation... No matter the introduction, Neil Gaiman's eponymous fairytale of gothic horror always leaves an impact.

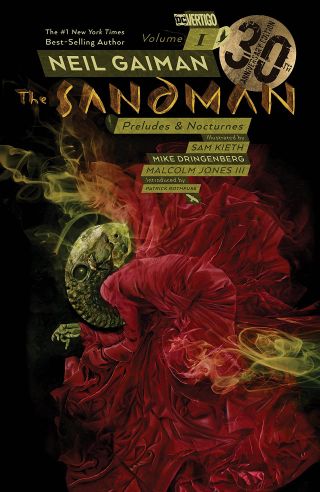

Written by Neil Gaiman

Art by Sam Kieth, Mike Dringenberg, Malcolm Jones III, and Daniel Vozzo

Lettering by Todd Klein

Published by DC

'Rama Rating: 10 out of 10

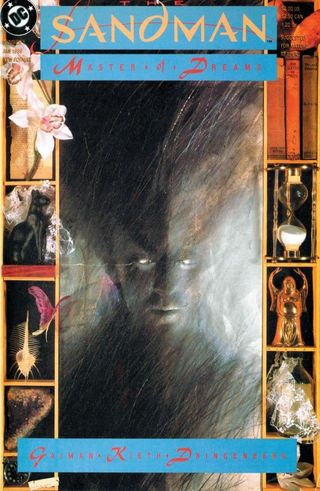

The Sandman's first arc, collected as 'Preludes and Nocturnes,' illustrated grotesquely by Sam Kieth and then in quite the opposite fashion by Mike Dringenberg, is initially a tale of pure horror. But as that first double-sized issue gives way to the series proper, its scope widens and Gaiman's vision of dark fantasy becomes clearer.

As far as plot goes, this is a simple tale. Dream (aptly named, as he's the Lord of Dreams) becomes imprisoned by an occultist for most of the 20th century. After finally breaking free and indulging in revenge, he seeks three totems of power he lost along the way: his pouch, his helm, and a magic ruby. In his quest to regain his lost trinkets, he travels from Hell to Arkham Asylum, rubbing shoulders with the wider DC Universe and shedding light on a whole new plane of existence as he does so.

The first eight issues of The Sandman are notable not for an elaborate plot, but for its overwhelmingly fresh tone. Narrated with literary flair from the perspective of the titular hero, Gaiman plunges the reader into a world of wild mythology. Dream lives in a decrepit palace populated with ancient mythical figures, is on a first-name basis with the myriad demons of hell, and has all the powers of, well… the god he is.

The Sandman #1 preview

Gaiman builds his world through little vignettes, at first describing the horrendous impact of Dream's imprisonment on the sleeping human race, then flitting between the sleeping and the dying depending on what the focus is at the time. When he's not darting behind closed eyes, he's immersing the reader utterly in alien worlds. Whether the setting is Hell or a diner in the thrall of Dream's ruby, Gaiman makes sure everything is utterly otherworldly.

As Dream transforms from prisoner back to fully formed god, The Sandman's first ac sees Gaiman experiment with the possibilities of a monthly series. Constantine, Etrigan, Martian Manhunter… there's nary an issue that goes by without a guest star. Thankfully, Gaiman integrates them in a sensible way that doesn't betray the series' strong voice. It is this flexibility and experimentation that are The Sandman's biggest strengths.

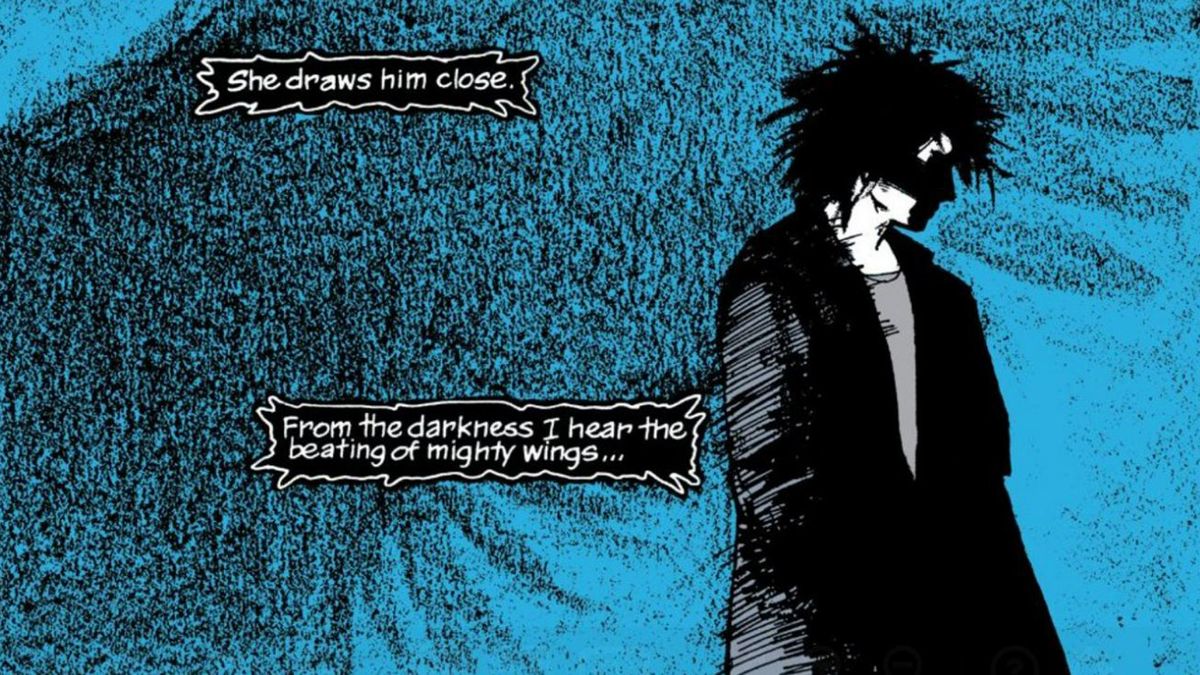

That otherworldliness is brought home by the two pencillers at work on these eight issues. Sam Kieth's pencils are imperfect, wildly varying in model, and often with technically incorrect perspective or scale. And yet his scratchy work only enhances the mental agony that Gaiman describes. There's an independent, punky feel to these early issues; a scrappy aesthetic not usually seen in a premium series. Kieth often frames the scene with ornate borders to match the antiquity of the series' protagonist and shapes his panels into bubbles looking outwards into a distorted world. His characters are craggy and scowling, with furrowed brows and sunken eyes. It is this intricate and alienating style that carries the more horrifying elements of Gaiman's script. Mike Dringenberg inks Kieth throughout with a heavy hand, blotting out huge sections of black to lend both depth and a gothic sensibility to the page.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

From the sixth issue onwards, Mike Dringenberg swaps his pen for a pencil. His cleaner and crisper illustration style immediately make itself known, replacing Kieth's funhouse mirrors with a fashion-conscious and almost seductive pseudo-reality. This is most obvious for Death's debut in #8, which is paradoxically the lightest in tone of this first collection of stories. Of course, Dringenberg's real contribution is the one he makes to Dream himself. Kieth's Dream is a sallow and aged figure, whereas Dringenberg softens his features a little and gives him a more casual modern-day outfit, igniting generations' worth of cosplay material in the process.

Daniel Vozzo's coloring dates these issues the most, with a harsh and contrasting style that works best in the gloom of night but can be visually jarring in bright of day.

Todd Klein's lettering is some of the best of its era, with a hand that drips atmosphere. Truly, this is how Gaiman's words should look, boxed into fragments of parchment and quivering with fear.

It is difficult to sum up a work like The Sandman. Truly format-shattering in its time and no less impactful in the modern-day, Neil Gaiman, Sam Kieth, and Mike Dringenberg have created eight disturbing and imaginative issues that worm into your consciousness and demand regular rereads. If you've not yet experienced The Sandman, you should be losing sleep over it.

The entirety of Sandman is available in print and on digital platforms. For the best digital comics reading experience, consult our guide to the best digital comics readers for Android and iOS devices.

Oscar Maltby has been writing about comics since 2015. He has also written comic book scripts for the British small press and short fiction for Ahoy Comics. He resides on the South Coast of England but lives in the longbox.