The miles we walk: How physical maps can guide the development of sprawling game worlds

Exploring the magic behind video game map creation

Maps are something we're all familiar with, yet few of us seek them out. Not like we did as children, anyway, sprawled on the floor with an oversized atlas, exploring place names, coastlines, and supposed routes with our fingertips. There aren't many among us who decide to get up one day, head to the library and have a really good look at a map, yet they're still an integral part of everyday life. Google Maps and iOS apps are incredibly helpful but can't always compete with the idea of unrolling or unfolding a giant map in order to plot a journey.

This is something which video games have explored since the days of BBC Micro, up through the 16-bit era and to today, where entire art departments are tasked with creating fantastical worlds. "We always do a paper map of the areas before constructing them," says Brian Heins, senior designer for Obsidian Entertainment. "That can help you identify major layout changes that need to occur, or to add locations for vista shots or hero-piece art assets."

Cartography is an important aspect of history, conjuring a physical depiction of something once thought intangible, and the idea of physical maps hasn't left general consciousness despite the prevalence of digital technology. We only need look to film and see that a traditional map is often used to depict travel, creating points and red lines to chart a course. If you saw the semi-recent Aardman animation The Pirates, you'll have noticed the motley crew sailing across paper waves, assailed by cannon fire and sea monsters as their dotted line trekked across the globe.

And it was the thieves of the high seas which first wowed Konstantinos Dimopoulos, video game urbanist and designer, who points to Sid Meier's Pirates! as an early form of inspiration for his love of all things topographical. "It came with a printed map of the Caribbean during the days of high seas piracy," Dimopoulos explains, adding, "and it made navigating the game-world both possible and slightly magical. Pirates! actually immersed me in its setting of buccaneers and lost treasure, and it's a map that I've kept."

Printed maps for video games are now very rare, usually bundled in as pre-order bonuses or with special editions of the game. Some are simply made by artistic fans because they don't otherwise exist. Even when they're given to us they're usually only earmarked for role-playing games; the two go hand in hand, after all, since you're often referring to a digital map to get from A to B within the game world itself.

A paper map, much like any physical object, grounds us in reality, but as technology guides us into new avenues of exploration, digital maps within games have to garner the same hold over the player. Death Stranding, for instance, utilises its map in-line with modern advancements via the ability to plot routes, monitor the weather and topography, and even tilt the DualShock 4 to shift the map's perspective and provide a better representation of mountainous regions

Putting the art in cartography

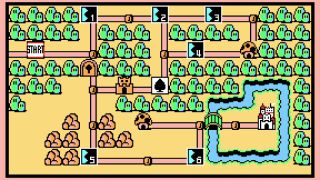

Once upon a time, video game maps were incredibly simple. Nothing more than an outline, with blocky markers highlighting points of interest. As technology moved forwards, so too did map creation and environmental design. It may not seem overly groundbreaking but even the 'overworld' map of Super Mario Bros 3 was meticulously designed to envelope the player into the universe, often acting as a precursor to what the player could expect from the levels. With its Piranha Plants, Flying Ships, Warp Pipes and shifting shrubbery, it gives the sense that the world is living and breathing outside of Mario's adventure.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But a straightforward journey from point A to point B never truly satisfies; within all of us is a yearning to explore. We need tangents, branching paths and forced decisions in direction. "Cartography has been a science and occasionally an art that has been around for thousands of years," explains Dimopoulos. "As its main focus is to successfully express abstracted geographical, spatial information and topologies in an efficient and pleasing manner."

Modern game design, then, must respect the traditions which came before it, and can even use them as a form of inspiration. In the era of 8 and 16-bit, players crowded around small CRT televisions, for instance, but games can now run on everything from laptops to 60" 4K TVs. This is something kept carefully in mind at Obsidian, according to Heins: "The game has to look good at each of those extremes. You have to combine broad shapes that read well from a distance with interesting detail you can inspect when you're up close."

But how does this design process begin? Before any visual form of conceptualising takes place, a team must plot out, in very broad terms, where their game is set. "The first phase is figuring out what the worlds and locations will actually be," says Heins. "Generally, there are two major influences. As an RPG company, our story is obviously one of those. As our team figures out the critical path story of the game, ideas for locations and worlds arise naturally – places like a restricted planet that's badly terraformed or an abandoned colony ship floating in space. It's at this point the story takes over, dictating the direction. We also talk about specific gameplay moments or visuals. These might be things like 'explore an asteroid floating in space' or 'fight through a secret research lab built in the side of a mountain.'"

Obsidian is a huge studio, with lots of designers and programmers. Each member of the team needs to be on the same page in order to collectively bring everything together from the design brief. "Once we have high level ideas for our major locations and moments, we put together what we call Region Design Constraint documents, or RDCs. These documents are the reference points for area designers, concept artists, and environment artists when they begin working on area," says Heins. "The RDCs outline all of the major story points that need to take place within the region, major points of interest, key enemies and NPCs that appear within the region, etc. It often contains a rough paper map of the region as well."

A map, within a game, puts the viewer of the object in control. You can look at a physical map, or even call up a location on your phone, but you take no action further than that. The beauty of games is being able to discover. They place a power in the hands of the player who, through exploration, wandering or general movement slowly uncovers a sprawling metropolis to be constantly recalled. Look at Minecraft, which uncovers biomes through movement, recreating what the great explorers once did. Whereas other titles give a vague outline or roads which disappear into blankness, waiting for the player to uncover the wonders out there.

"I honestly cannot think of something that gaming gets consistently wrong in its world design"

Konstantinos Dimopoulos

Now we have an overarching map, a real world in which an adventure can take place is truly made in its detail. It could be the varied areas of Hyrule, a distant future or a fantasy based loosely on historical events. Now this is in place, we zoom in and begin to flesh out the world itself. If the map represents a body – the fleshy outer shell – then the cities and locales are the organs which keep everything functioning. Humans have always been nosey and voyeuristic, it's why we like Street View so much. And this attitude of exploring everyday life must be present first and foremost when designing the intricacies of a video game world. The environment needs to feel lived in, something which can be done visually nowadays, whereas years ago it would have taken place in narrative text over a usually static 2D background.

That's not, Dimopoulos emphasises, to discredit designers and programmers of old, clarifying that "sometimes simply conveying a feeling is enough, and other times a well written paragraph can do surprising amounts of heavy lifting. Vast carefully constructed open world maps can feel artificial and pale when compared to a few static backgrounds tied together by simple yet elegant maps."

The last thirty years has seen environmental design evolve from Guybrush Threepwood casually deadpanning his surroundings to vast spatial areas where players could physically move their character to investigate the smallest detail. "You want to ask," Heins continues, "'Where do people sleep? Where do they eat? Take a bath? How do those basic elements of existence express themselves in your world?'".

Players, especially of detailed RPGs or sprawling open world adventures, will always wander around looking for secrets, clues, or Easter Eggs. As worlds grow, so too does our intrigue. "In The Outer Worlds we made sure to include things like break rooms, kitchens, cafeterias, and bathrooms in our spaces. Those details help establish the idea that people actually live in these spaces. Also – nothing in The Outer Worlds is new. Everything has a level of grime, things are scratched or broken, nothing works perfectly."

Charting course

It's these game worlds which obsess the mind of Konstantinos Dimopoulos, whose book Virtual Cities: An Atlas & Exploration of Video Game Cities explores these worlds in greater detail. "The real world crucially informs how everyone perceives things around them," he says, "and thus also the digital settings of games. All our experiences have been shaped and defined by reality; it has defined our preconceptions of what other realities should or would look and feel like."

Technological constraints perhaps stopped developers of the '80s and '90s realising the true potential of their worlds. The intricacies of life are often manifested in our games via leaking taps, creaking trees, swinging vines, or the creeping shadows of candlelight, all now achievable with pixel graphics or 3D rendering.

Whether a game represents life as we know it, or imagined far off visions, the details have to be grounded in what we know, in order to be relatable. "We know, for example, how gravity affects things, how iron rusts, what a bed should be able to provide, how cities tend to function, and how the sea sounds," Dimopoulos explains. "An imaginary, exotic place that hopes to provide us with even a momentarily convincing illusion has to play by the rules we understand."

Heins agrees: "At a high level, we try and blend elements of the fantastic with more grounded real-world ones. Those everyday relatable elements help players accept the fantastic."

Of course, video games as a medium for storytelling have an advantage over other forms of entertainment, stemming from its interactivity and the space to be larger than life. "I honestly cannot think of something that gaming gets consistently wrong in its world design, besides, perhaps, a very slight tendency towards placing too much focus on the spectacular at the expense of the mundane," says Dimopoulos.

But, he argues, it doesn't matter whether we're faced with trawling through the intestinal tract of an alien or simply exploring a spooky attic space in monochrome, the goal is always the same. "There is though one rule I believe applies to all game worlds, and this is that things simply have to make sense if they are to be believable. We have to construct cohesive and interesting illusions if we are to offer believable worlds to our players. And when things are believable and, even better, memorable, then a spatial sort of immersion in imaginary worlds can be achieved."

The process of creating a world or universe is huge. Everything, from the map maybe scribbled on a Post-it note, to the apartment in a 23rd century city dashed out in a stark 3D design, is used to allow the player to step from one reality into another. Both of those examples are established in history, from pioneers to architects, using real world experience to establish an imaginative expanse. As sci-fi author Philip K Dick once said, "I want to write about people I love, and put them into a fictional world spun out of my own mind, not the world we actually have, because the world we actually have does not meet my standards."

Think of the worlds you've crossed in your gaming career; the miles you've walked. They may have been recreations of Venice, dense wilds lurking with danger, a land of fantasy with a grand castle dropped in the middle. Maybe you marked out your journey or followed a linear path- one could be filled with procedurally generated planets, the other a route into hell. But each was crafted and based on exploration guided by details and discovery, the basis of knowing our place in a world. As Dimopoulos recalls: "The great Hayao Miyazaki has shown us that the love and attention for little, simple things can really flesh out a world."

Check out the biggest new games of 2020 and beyond still on the way this year, or watch the attached video below for our latest episode of Dialogue Options.

Dan has been playing games for over thirty years, from back when controllers had one button. Thankfully he has managed to keep up with his favourite hobby at his age. You can normally find him playing Roguelikes or Battle Royales, both of which are his specialist subject. When he isn't playing games, he's writing about them in books and articles. If he had to pick a favourite game, it would be The Binding of Isaac or Final Fantasy IX.

"Minutes after Palworld released," Pocketpair was already getting game pitches from "some really big names" before it even set up its own publisher: "No one has money at the moment"

Palworld dev "secretly" brought a game it's publishing to an event that's "not like anything we've been involved in" and reactions are "very positive"