The making of Outer Wilds: Exploring the many reincarnations of Mobius Digital's transcendent space adventure

How a small team out of LA created one of the best games of 2019

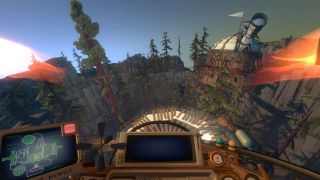

Like The Legend Of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Outer Wilds gives you a world of wonder to explore in a lashed-together ship. However, you aren't setting sail over waves; you're launching into the deep blackness of space in a jerry-built spaceship. The solar system you fly out to explore is dotted with planets hiding beautiful mysteries. The Hourglass Twins, for instance, are two planets orbiting one another; sand empties from one and fills the other, at once revealing hidden caves on the first and filling up the valleys and crevices of the second. Another planet, Brittle Hollow, has a black hole for a core and its fractured crust is collapsing inwards under a hail of meteorites.

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

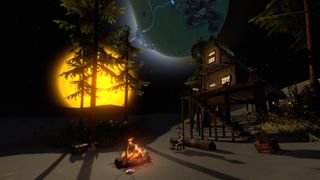

A third, Dark Bramble, is a nest of thorny vines wrapped in fog, and hiding within its cloud are whale-sized anglerfish that will eat your ship whole. Perhaps the greatest wonder, though, is that you have only 22 minutes to explore it all before the yellow sun at the centre of the solar system shivers and shrinks, turning blue and exploding outwards in an all-consuming supernova. Whether you're in space to meet the destructive wave or stayed on the planet where you woke, toasting a marshmallow on the firepit, the blast kills you and begins the loop anew.

This arresting game has been nearly a decade in the making, beginning life as a Masters thesis back in 2012. Over the years it has won awards and launched crowdfunding platforms, before picking up a publisher. At each stage it has been remade, but the developer has stuck strictly to its initial concept. "The goal from the outset was to make a game that felt like we're going off and exploring the unknown," Outer Wilds' creative director Alex Beachum says. "Very specifically, a world that's governed by natural forces that you can't really do anything about, but as you learn about them you can understand it enough to not immediately die."

Life after death

Beachum began work on Outer Wilds at the University Of Southern California as part of the Interactive Media programme. He and a team of other students pooled prototypes they had been developing and "gradually duct-taped" them together to make a game about exploration. Unlike other exploration games, where you gain abilities that let you access new areas, the team wanted the player to only "collect knowledge about the world they're exploring".

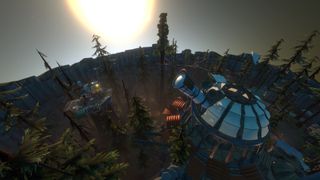

The team structured Outer Wilds around what it called 'Curiosities'. These were major hidden locations in the game that players could only reach when they had acquired the knowledge to access them. "The idea was everything else in the game was going to be a clue that would tell you about the existence of the super-secret mystery," Beachum explains. One example is the coral forest at the core of Giant's Deep. The planet is a gas giant with tornadoes raging around the surface. Players can only get to the core by flying into the one tornado on the planet that is rotating anti-clockwise, something they learn in an observatory on another planet – a planet which itself is a puzzle to enter. After the team had settled on the Curiosities and the secrets to accessing them, they mapped out the solar system on a whiteboard and distributed clues on the different planets.

The Curiosities structure drew from and fed into Outer Wilds' still-forming narrative. For instance, the team had long had the idea for the Hourglass Twins in mind. However, it was only in distributing clues between planets that they decided to place the escape pod of an ancient alien race, called the Nomai, on one of the Twins. The Nomai was a race of advanced beings that became stranded in Outer Wilds' solar system; uncovering the story of what happened to them and finding each of their hidden settlements is a large part of the game. In deciding to place the escape pod, the team had the idea that the stranded Nomai would have settled on the planet, building a city in the underground caves. "It was this constant back and forth," Beachum says. "Design, writing and story all moved as one."

The student team built a working version of Outer Wilds, one that was enough to fulfil the requirements of a Masters thesis, but it was still far from a complete game. It still had "literal greyboxes," Beachum says. Much like the cobbled-together spaceship you fly in the game, put together by the natives of Timber Hearth, who so wish to see the stars they'll slap rocket boosters on a barely airtight tin can and call it a spaceship, the next few years for Outer Wilds are an example of just-in-time funding and opportunities.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Knowledge is power

After graduating from USC, Beachum went to work at Microsoft as a designer on what became Project Spark. Meanwhile his friend and collaborator on Outer Wilds at USC, Loan Verneau, co-founded Mobius Digital with Masi Oka, who may be best known for playing Hiro Nakamura in Heroes, but originally trained as a visual effects artist and worked at Industrial Light & Magic on the Star Wars prequels. Shortly after Verneau founded the company, Beachum was offered a job at Mobius to work on mobile games. In his spare time, Beachum continued to work on the Outer Wilds prototype they'd developed at USC and submitted it to the IGF. In March 2015 it won the Seumas McNally Grand Prize.

Off the back of its success at the IGF, Beachum and Loan brought the project to Oka who agreed they should make it as Mobius' next project, bringing the rest of the team to work on the game and turning it into a commercial product. The $30,000 in prize money helped, but winning also opened doors. In August 2015, when crowdfunding platform Fig launched, Outer Wilds was the first project it promoted. Through it the team raised $126,000. Combined with money from Oka, the team of six had enough funding to work on the game for around nine months and wrap up Outer Wilds' development.

"It's funny, Outer Wilds is full of like shit that says, 'Sometimes just random natural disasters happen', like the comet that kills the Nomai," Beachum says. "But they didn't for this project. We've just been stupidly lucky, repeatedly."

With funding behind them and a filled out team of full-time developers, Mobius mapped out what Outer Wilds needed to be a fully fledged game. "Originally it was going to be much shorter, much smaller," Beachum says. The plan was to finish what they'd built in the alpha, complete the art, and "call it a day".

It was what Beachum calls the "polish it up and kick it out the door" version. Though, he admits it didn't stay that way: the team at Mobius kept adding more to the game when they were supposed to be locking it down. Luckily, success at the IGF and getting fully funded through Fig had caught the attention of Nathan Gary, a producer at Annapurna Interactive. In late 2016 Mobius began discussions with the publisher and signed a contract in early 2017.

Ironically, signing on with Annapurna actually meant scrapping a lot of work. "We ended up basically remaking all the art, because essentially," art director Wesley Martin says, "the way art for a game works is that you figure out how much time you have and then you make it to the quality level you can achieve within that time. With that nine months initial shipping goal all the art was super-rushed." Martin and the other artists had been focused on making sure there was all the art the game needed first before worrying about its quality. "Whatever time we had left over we'd spend polishing the important bits. But with nine months, that wasn't a lot of extra time."

When Annapurna got involved Martin and the team had to "rethink everything from the ground up". They spent a year with Annapurna looking "super-critically" at the art and defining the style of Outer Wilds. More than that, though, it was about working out how to produce high-quality art that fit the unique constraints of Outer Wilds.

“One of the core pillars of the game was having a world that feels like things are happening even when you are not there,”

Alex Beachum

"One of the core pillars of the game was having a world that feels like things are happening even when you are not there," Beachum explains. And to do that, they decided they wanted to simulate the whole system so it did, literally, run even when the player wasn't there. "That's part of the reason for the time loop; it originally existed to get away with pulling some of this shit, like planets falling apart, and these irreversible things happening," Beachum continues. "And because everything's smaller-scale, they orbit way faster, and you just get this sense of this very chaotic, dangerous place."

The simulation was a constant challenge for the artists and programmers. "Every single planet is actually being physically simulated in orbit," Logan Ver Hoef, one of the team's only two full- time programmers says. "And we never unload its collision data; we have systems and they're still running in a low-level detail version when you're away from them. That's a big part of the technical approach to Outer Wilds, we're doing our best to find the right level of verisimilitude."

What exacerbated this challenge was that the player could stream a view of other parts of the solar system. The player is equipped with a scout probe which they can fire into the distance and use to take photos which then appear in their HUD. If the player fires their probe at another planet, the game has to start loading in the assets the player could potentially see if they were to take a photo, putting increased strain on the hardware. "On PC, it does a pretty good job at being loaded and ready to go," Ver Hoer says. "But the Xbox is a big challenge because it has a really slow hard drive."

Space jam

The team developed a number of tricks to stop players seeing parts of the solar system before assets had loaded in properly. "We handcrafted low-res versions of models," Martin says. "A lot of games automate their LOD stuff, because you'll never see them up close. In Outer Wilds, because of things like the remote viewers, or the fact that you can be going 1,000 kilometres a second and slam into a planet, we tried to make our LOD versions of assets look very close visually to the actual version. So it uses way fewer resources, but if you squint your eyes, it kind of looks the same. So that it's not jarring when it streams in."

Like Outer Wilds' protagonist, however, the team had knowledge from previous 'lives' that focusing on solving those problems would pay off. That had been the case for the first version of the game, which went from a clutch of prototypes that were duct-taped together to become a Masters thesis to as an award-winning alpha, and then became an unfinished crowdfunded version. The team knew if they stuck to their strict rules – about how players would discover Outer Wilds' secrets, how the solar system would operate around them, even how they wouldn't be able to fix the Groundog Day time loop and stop the sun from going supernova – that it would pay off in the experience the player would have.

"Even at the start of the project you could go play something to make you think, 'This is what the game feels like, this is the feel we want to translate into the final game,'" Martin says. "A lot of games have design documents; for us that was the design document. It's like you're constantly referencing that. When we were coming up with final art style or when we were doing optimisations, we would always be looking back to that prototype. I really feel that's good." "Coming into a full production cycle with a version of the game that worked, and you knew on some level was good," Ver Hoer says. "That's incredibly rare to have. It was a huge asset."

"In my mind," Beachum says, "it was like a proof of concept that it was worth the trouble."

Subscribe to Edge Magazine for only $9 for three digital issues and show your support for long-form game journalism

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.