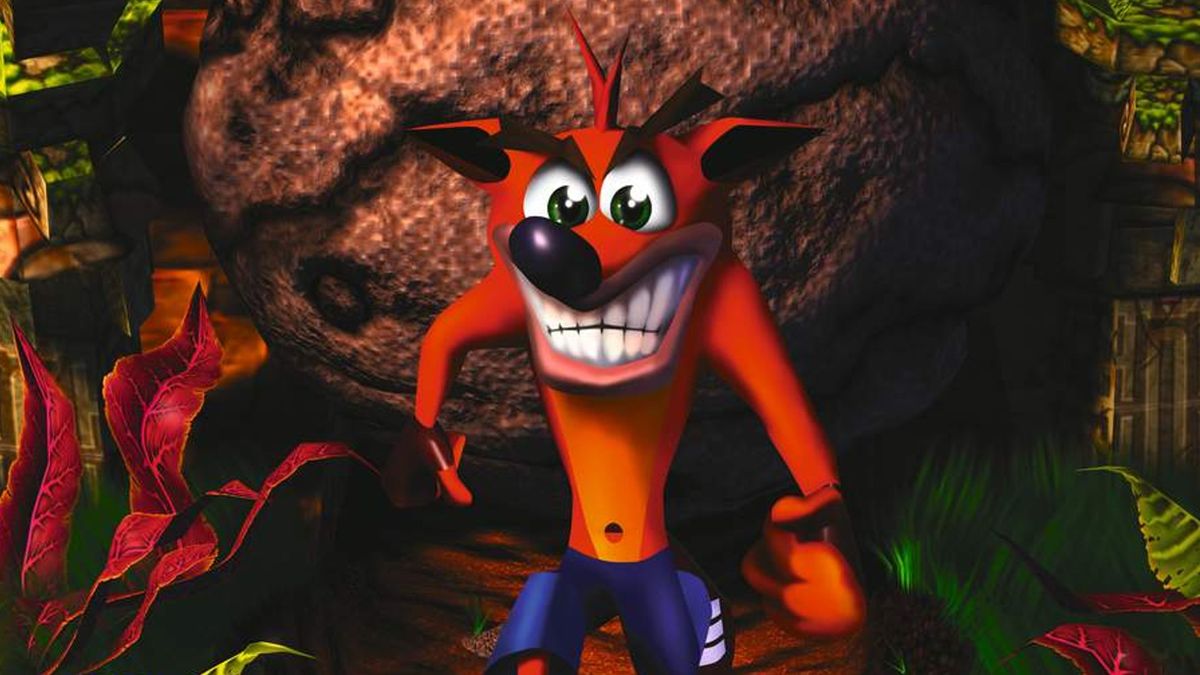

Crash Bandicoot turns 25 – How Naughty Dog transformed Willie the Wombat into a PlayStation icon

Retro Gamer explores how Crash Bandicoot shaped 3D platforming, the PS1, and even Naughty Dog itself

For those who lived it, the launch of the PlayStation was an exciting time for the video game industry. Not solely because of Sony's new upstart console, but instead because the 16-bit generation that had preceded it had proven the value of gaming and now was the time for the industry to transition from toddler to teenager. This meant true 3D gaming, this meant mainstream acceptance but, more than anything, it meant an increased interest from all avenues. Hollywood, in particular, had become enthused by this new form of entertainment and with Sony getting involved, it was time to step up. This, as it happens, is how Crash Bandicoot came to be: from the interest of Universal and a happenstance meeting between a pair of developers who, back then, weren't quite the big names they are today.

"Skip Paul [then vice president of production at Universal Studios] had the vision to get into the video game business, and at that time all the studios were somewhat opening up divisions," explains David Siller, one of the key producers on the original Crash Bandicoot. "Well anyway, Skip gets Universal to agree to put up money to start up this division." What this meant was a huge injection of cash for what would become Universal Interactive, giving the company the opportunity to invade the video games market and, as Siller suggests, hope to one day create games – and even interactive movies – based on Universal's existing franchises. As such Universal Interactive was eager to buy up small, independent developers that it intended to use to bring this future into fruition and the Hollywood studio really was throwing money at the challenge.

Naughty Dog's big challenge

Naughty Dog, having yet to find a hit, had gone big on the 3DO, with Jason Rubin and Andy Gavin investing in a development kit for the console in the hopes of making it big. Their game, Way of the Warrior, had been one of the key titles that 3DO wanted to display at CES, bringing the duo into the expo to show it off. As luck would have it Naughty Dog found itself running a booth right next to Universal and, over the course of the days that followed, ended up striking a deal with Mark Cerny and Rob Biniaz who was in charge of getting Universal Interactive off the ground. "It was one of those things that they were in the right place at the right time for their future," says Siller, and without that opportunity it's unlikely Naughty Dog would ever have become the household name it is today. "Naughty Dog lucked out by being put in a position next to Universal at CES: this big 'more-money-than-God, NCA-owned powerhouse' next to just these two guys that were very, very talented and had a little bit of money and developed their own fighting game."

- 26 years later, Codemasters' Chris Southall talks Colin McRae Rally: "We wanted to do something that was an authentic rally experience for the hardware of the time"

- "We were honouring Sonic's holistic history which includes both designs": 13 years on, Takashi Iizuka reveals why Sonic Generations need twice the 'hogs

The deal was for a set of three games, an atypical agreement that meant that Naughty Dog was locked in so long as it could make a product that reached Universal's lofty hopes. "Universal really wasn't saying there was a budget," adds Siller, "and that continued throughout the course of Naughty Dog's existence at the company." The design of the game, meanwhile, had been determined from the start. It was all in a six-page design document written up by Jason Rubin, detailing the gameplay and story of what was then named Willie The Wombat. Key elements that are recognisable were all in there, the behind-the-character camera viewpoint, the marsupial character, the different level styles, and cameras.

"I was told that I would be the producer of those guys on Universal's side," Siller explains, "and I met them and they told me, 'Hey, we don't want a producer,' but they were nice enough at the time. But I started designing the game from day one, because that was my expertise. That's how I got involved in the project, I was hired in and assigned to those guys and even though they didn't want a producer they eventually learned the value of my participation. Even at some point I was asked if I wanted to join Naughty Dog, which I didn't." While Andy Gavin began working on the technology to power the 3D platforming environments, Jason Rubin and David Siller worked with the six-page design document and began fleshing it out into the title that would dominate the charts.

"I coordinated on the design with Naughty Dog and Cerny along the way, but they were all focused on getting all the tools and art programs and technology together and I focused on the gameplay. It consistently evolved," says Siller of the way the design document changed over the game's development, "there were new bibles written." While Siller initially designed elements of the game, as producer he was not implementing them – it was Naughty Dog's project, after all, and Siller worked for Universal. "I mentored Naughty Dog design-wise, but they were initially allowed to try and create the gameplay and that was going to be a milestone that they were going to have to clear called the 'first-playable'."

This milestone was not achieved, however, the game itself was failing to offer much in the way of gameplay. "It had no gameplay," states Siller. "Willie was running around and interacting very poorly with anything and everything. There was just not a lot of gameplay. You couldn't look at the game at that point and say, 'Wow, this is a must-have game, this has the potential to be that.' It wasn't. I don't see how it could have been. The team did not have the expertise in design and planning this type of game."

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

As a result of this, Mark Cerny brought Siller closer into the project, using his experience from working at Sunsoft to help Naughty Dog turn Willie the Wombat into a title that Universal would be proud to have. "So I took the ideas that I had and put them together and showed that the game could work and become a great game," explains Siller. "I went into Andy Gavin's office and helped him work on Crash. He once came to me and said: 'We need to work on Crash's jump, and his gravity,' and we went and spent several hours together, and I had the controller in hand and we kept tweaking and tweaking Crash's jumping up and his gravity and how he would rebound, he wouldn't float. It was a collaborative effort the whole way."

Willie the Wombat

With a solid foundation now created and refined, Willie the Wombat succeeded its first-playable milestone and, with Universal's hopes sated, it went to seek a publisher for the game. Universal ran a trademark check to ensure Willie the Wombat was available, only to discover that the name had been used by Hudson for its Japan-only Sega Saturn RPG Willy Wombat. "That game was kind of an action RPG," adds Siller, "it wasn't very successful in Japan, didn't get published beyond that. But it was an interesting-looking bipedal wombat, looked very similar to Crash Bandicoot in a way, but even more stylised with that Japanese anime look."

Jason Rubin and Andy Gavin had insisted on the name from the start, a carryover from the 16-bit era where catchy names for mascot platformers was the biggest aspect to many of the games released as they all sought to dethrone Super Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog. But this was a new generation, it was about to become the PlayStation era and Willie the Wombat's rebellious attitude needed a name that could stand out. Universal arranged a meeting with both Universal Interactive Studios and Naughty Dog so a replacement name could be found. "At that meeting, a lot of names were bandied about," says Siller, "I believe a couple of guys at Naughty Dog had suggested 'Crash' and that it would be a bandicoot instead of a wombat. Everybody seemed to like that: 'Crash Bandicoot, okay, that's catchy'. From that point on it was resolved, Kelly said, 'Okay, everyone raise your hands, Crash Bandicoot.' That morning we went from Willie the Wombat to Crash Bandicoot. A bandicoot was also a marsupial, we just switched one for another."

Now ready to shop the game around, Mark Cerny, Rob Biniaz and David Siller took the prototype to Sony to get concept approval, a process that – back then – was a necessity if you were to get onto the PlayStation. The meeting was a complete success, with Sony's executive vice president Bernie Stolar becoming immediately enraptured by the title and signed the product as a PlayStation exclusive there and then. "When we left we were as high as a kite," recalls Siller, "we knew we had done an impressive thing. Whenever you want to get someone's attention, you take them something that isn't maybe complete or finished, but you take them something that knocks their socks off. You go and show what your idea is, and show them in real time why you have a hell of a product. Bernie Stolar saw that. Sony came in and obviously had to have Crash."

This was a significant moment for the orange marsupial. Siller explains that the character was set to be a Universal mascot, a character that it would use to build itself as the "modern Warner Bros." to compete with the Looney Tunes characters. "We were thinking that where Warner Bros. has Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck and Tasmanian Devil – they have a list of characters – Universal really didn't have that and we felt we were creating that for them. Crash, as well as other undiscussed game character plans that were being developed that never saw fruition."

The Mario 64 of it all

But Crash's aesthetic was more than just an idea to take on Warner Bros; the character itself had been inspired by the Tasmanian Devil himself, from his appearance to his anarchic attitude. "Jason Rubin, in his document, had explained that he wanted this wombat character that would run upright, a bipedal character," says Siller. "The big influence he had was that he wanted to model Crash after the Tasmanian Devil." This was a focus for the design of the character, an element that Jason Rubin had decided upon from the start that was tougher to implement than it might first seem. "Well, the Tasmanian Devil had no real neck. The head kind of just sat on the shoulders, and Jason insisted upon on that. Charles Zembillas [art director on Crash Bandicoot] told me on a number of occasions that he had a big problem with that – it didn't lead to good turn animations and so forth." He continued to work on it, however, eventually forming the iconic character that is remembered so fondly. "Crash was this hybrid marsupial, Tasmanian Devil spiritual competitor type character. He had no neck, he was a little more slender but he was Universal's Taz."

It wasn't only the visuals that this inspiration helped create, either. Where the Tasmanian Devil was well known for his whirlwind frenzy – an element that was also used in his own 16-bit video game – Crash had also adopted a similar technique, but evolved to make for more rewarding gameplay. "Well Crash had a shorter, more controlled spin that didn't cause him to go out of control," says Siller, "and that was developed to be a timed sequence so that the closer you got to an enemy you could spin and knock them out, but if you did it too soon and you come out of the spin as you touch that enemy then you would be damaged or you would be defeated."

"That morning we went from Willie the Wombat to Crash Bandicoot. A bandicoot was also a marsupial, we just switched one for another."

This, many will recall, was the death of many a marsupial, and added to the game's challenge and appeal. Despite the excitement from Sony and the obvious quality of the product, there was no guarantee of Crash Bandicoot's success. It was only towards the end of development that anyone really believed there could be something outstanding. "The Naughty Dog guys seemed to be nervous about everything," admits Siller, suggesting that Nintendo's Super Mario 64 was especially worrisome for the team. "They would go [into the games room] and play Mario 64, they were always concerned about other games. But I felt that our pick-up-and-play gameplay was going to prove to be popular. I wasn't really worried about it, but there were others there that were."

Towards the end of the game's development and following a lot of positive coverage in the magazines of the time, internal belief in Crash grew, but no one – Sony included – could have predicted the booming success it would end up becoming. "The reason I wasn't so sure that it was going to be special until it came out was because we thought there were going to be a lot of similar games. There were a lot of competent developers out there, and we were coming out of nowhere, really. Where are the Konamis, the Namcos, the Crystal Dynamics? And they all did, they all came out with stuff, but nobody did as soon as we did – and for a long time – like we did. It took a while for the Crash Bandicoot influence to proliferate into the development community. And then Crash clones and Crash-influenced games were right and left. No, I don't think we knew that it was going to be that big. At least I didn't. Maybe Jason, Andy, and Mark immediately knew that it was going to be substantial, and that's why they clamoured to take all the credit."

Tension behind-the-scenes

If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer today.

Not all was well internally at Naughty Dog, however, a hidden history behind Crash that has been shrouded since its release. Jason Rubin and Andy Gavin, claims Siller, were keen to weaken the impact that his design and input had on the game. "Not only me," says Siller, "but especially me, Charles Zembillas, and Joe Pearson pretty much got pooped on." Zembillas and Pearson were key in the visual aesthetic of Crash Bandicoot, with the pair creating the unique characters while Pearson also created concepts for what the world would look like. "And I took those and it influenced me to design gameplay, the design kept going, and evolving. And even Naughty Dog participated in that after I had shown and proven the way."

After increased tension for Siller, the straw that broke the back was when he spoke to Mutato Muzika – the company arranging the audio for the game – and agreed to include some of their music into Crash. "Well apparently that information got back to Naughty Dog and Jason Rubin flew off the handle," says Siller, "and called me into his office, closed the door and started yelling at me and telling me that I had no business telling Mutato Muzika that, saying that Naughty Dog was in charge, and that they were going to run the music. I tried to reassure him that I didn't talk to the press and that I was only, in as far as Mutato Muzika, a soldier under command. I was doing what I was told to do. But apparently Mark Cerny didn't back me up. At that time he said, 'They don't like you, they want me to be in charge now.' It was the final month or two, and that's what happened."

Despite the feud that had formed, Crash Bandicoot released in November 1996, only a year after the release of the PSone and to great critical and commercial success. "As soon as the game came out, Sony knew that it was a hit," says Siller, the game's unique approach to platform game design and the attitude of its characters helping to create a game that was immediately loved by many. The series built up such a devoted audience, in fact, that the rebirth of classic PSone-era Crash gameplay is one of the biggest request from PlayStation fans. Perhaps now is the right time for the world to have a bit more of the orange marsupial in their lives.

"I think any time you can develop a game that allows the greatest number of people to come in and instantly be able to play it," suggests Siller of how the game surged to popularity and remained so important, "without sophistication or complication, without difficulty and is fun, and it looks good and has robust colour then I think that game will become a big success. That's the reason Crash became the staple that it is, because it had all those elements."