The Making Of Apocalypse Now

Plus exclusive new images

Bring On The Apocalypse

“They used to call it Apocalypse When ,” recalls director Francis Ford Coppola. “It was just being portrayed as this wild, irresponsible picture.”

It’s not hard to see why. Tormented by a production that suffered one disaster after another, Coppola’s Vietnam War movie Apocalypse Now looked like it might never see the light of a movie projector.

Wrestling with a tricky subject matter was taxing enough, but Coppola faced numerous problems during production of his magnum opus – including torrential weather storms that destroyed expensive sets, a problem actor in Marlon Brando, and a runaway schedule – not to mention a runaway budget.

It’s a small miracle that Coppola was able to piece together the kind of film that was even viewable, let alone one worthy of an Oscar or two...

Heart Of Darkness

Apocalypse Now began with one man: Joseph Conrad. Born in 1857, he died 15 years before Francis Ford Coppola was even born, and is buried in Canterbury Cemetery.

Yet Conrad’s legacy was such that it echoed right through the ages, until his most famous novella, Heart Of Darkness , ended up busting into the 20th century as a full-blown blood-and-guts movie blockbuster.

Before that, though, Darkness was a three-part series published in Blackwood’s Magazine . The story detailed the travails of Charles Marlow, an Englishman who becomes a ferry-boat captain in Africa and is ordered to take mysterious ivory trader Kurtz downriver.

Conrad’s novel is chiefly concerned with exposing the horror of European colonisation (which he witnessed as a Congo steamboat captain), doing so by peering into the dark heart of the Congo while simultaneously laying bare the evil in the colonising man and his mistreatment of natives.

Published in book form in 1902, Conrad’s work is now widely taught in the US curriculum, and has been commended for its realistic portrayal of colonisation. Almost 60 years later, screenwriter John Milius thought it might make a good movie...

Adaptation Now

John Milius was working as an assistant on Coppola’s The Rain People when his friends George Lucas and Steven Spielberg encouraged him to write a Vietnam War film.

As a fan of Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness novella, Milius spied an opportunity to draw an interesting comparison between the colonised peoples of the Congo, and the natives of Vietnam who suffered a similar injustice.

“I wrote the original screenplay for that in the office that's right next to mine at Warner Bros. now,” Milius recalls, “that the Wachowskis are in. The same building, two offices down.”

What got him interested in making something like Apocalypse Now ? “It was a real desire to make a Vietnam movie,” he says. “I read Heart Of Darkness when I was 16 or 17 years old, and I never read it again. So I decided not to read it again. I wanted to sort of have Heart Of Darkness as if I'd dreamed it... I wanted my original interpretations of it.

“Of course, nobody was making movies about Vietnam except John Wayne, he made a movie about Vietnam – and it was successful, too. Warner Bros. made it, actually. But nobody else was going to make another, a real Vietnam movie...”

The Psychedelic Soldier

Milius was paid $15,000 by Coppola to write his script (that’s what the writer said he could live on), with a promise of a further $10,000 if the film eventually got made. By the end of 1968, Milius had gone through ten drafts and over 1,000 pages before he finished his script – titled The Psychedelic Soldier .

A nightmarish vision of war on the frontline, it followed Captain Benjamin Willard, a US Army special operations officer who’s enlisted to enter the Cambodian jungle during the Vietnam War. There, rogue Colonel Walter Kurtz has turned himself into a god, ruling over the natives while slowly going insane.

Coppola, though, was never in line to direct – it was George Lucas who fancied the film for himself. “He wanted to do it,” Milius remembers, “but you know, Warner Bros. had this thing, it was Black Thursday or something where all of Francis's deals got cancelled. All these guys were left out in the cold.”

Lucas had planned on making the film for $2m in a loose documentary style, with an idea of shooting in the rice fields between Stockton and Sacramento in California. But by then Lucas had started getting American Graffiti off the ground, which led to the first delay of many in Apocalypse Now ’s production.

A quick title change later (Milius based ‘Apocalypse Now’ on a button popular with hippies in the ‘60s that read ‘Nirvana Now’), and Coppola had become interested in Milius’ script. In 1974, while filming The Godfather Part II , he became adamant that Apocalypse should be his next project...

Acoppolypse

Coppola recalls that moviemakers of the ‘70s approached filmmaking in a completely different way to today.

“With Apocalypse Now ,” he says, “it was, ‘Wow, we have this incredible script and we'll make a great big picture like A Bridge Too Far or The Guns Of Navarone , and it will make a lot of money, and then we'll have money to make little personal art films.’

“Look, the whole reason one wants to do lower budget films is because the lower the budget, the bigger the ideas, the bigger the themes, the more interesting the art.”

It was a theory that he had hoped to apply to Apocalypse Now . As George Lucas took to the stars for an altogether different kind of war movie, Coppola scouted Australia during the Godfather Part II press junket there for possible locations to shoot Apocalypse Now .

Opting for the Philippines as a Vietnam-like location perfect for the movie, Coppola spent the end of 1975 honing Milius’ script and attempting to secure funding from United Artists.

Having bumped up $8m of his own company’s money on the movie, UA agreed to contribute $7.5m to Coppola’s $12-14m budget on a proviso that Apocalypse Now would star Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen and Gene Hackman. But McQueen wasn’t interested...

Casting The Net

With Apocalypse Now set to shoot outside of the States for a gargantuan 17 weeks, Steve McQueen declined an invitation to play the lead role of Willard. Al Pacino also turned down a role after concerns about falling ill in the jungle again – as he had done while shooting Godfather Part II.

After these setbacks, Coppola recalled a young actor who had read for the part of Michael during casting of T he Godfather , and invited him to play Willard. That actor was Martin Sheen.

As (typically bad) luck would have it, Sheen was already committed to another movie, and Coppola settled for Harvey Keitel in the role instead. Meanwhile, the erstwhile director managed to secure the film’s biggest asset, Marlon Brando, by dangling a giant juicy carrot in front of him. A carrot that cost $3.5m.

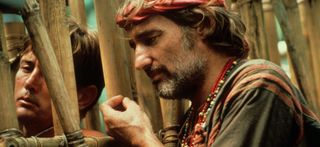

Rounding out the principal cast, Dennis Hopper was brought in, though at this point he had no idea what his part would end up being. The movie’s final scenes had yet to be properly written by Coppola...

Apocalypse Now

In March 1976, Coppola flew with his family to Manila where they rented a house that would be their home for Apocalypse ’s proposed five month filming period.

But just a few days into shooting, Coppola wasn’t happy with what Keitel was doing with his version of Willard. The director noted that Keitel “found it difficult to play him as a passive onlooker”. His concerns were confirmed after he viewed early test footage, and Keitel was replaced with Sheen, who by now was free from his other contractual obligations.

Two months into shooting, however, production was shut down after Typhoon Olga destroyed numerous sets in Iba. An entire month’s scheduled shooting was ruined after the Playboy bunny set was torn apart by the typhoon.

Adding to the chaos, the entire payroll was stolen. The film had already fallen six weeks behind. And the budget had ballooned by $2m. “I was under great strain,” Coppola remembers. “Partly because we didn't have an ending and because it was my own money. But it produced a very oddly appropriate film for that subject matter.” Sheen didn’t help matters...

Taking The Sheen Off

Sheen was a mess on set. Drinking heavily, he had his family around him, including 14-year-old Emilio Estevez, who recalls that period of his life as a living hell.

“I just wanted to be home,” Estevez told The Times recently. “I was losing my mind. I hated him when he got drunk, because he’d get violent. Some of it he may remember, some of it he may not.

“But, yeah, it was horrible. And because I was the oldest, it was always directed at me. But I think the Philippines was the last physical fight we had. The older I got, I started lifting weights and getting stronger, so I was like, 'Come on, let’s go…'’

The film’s opening scene, in which Willard sits and stews and slowly goes crazy in a hotel room, is a fair representation of Sheen’s state during the shoot as a whole. It was Sheen’s 36th birthday, and he was genuinely pissed...

“That was a crazy time,” Sheen remembers. “The [ kids ] came away with me a lot, especially when they were little and didn’t really have a lot of say in the matter. I just grabbed them out of school and took them to some pretty remote places.”

After 12 months of shooting, Sheen finally hit rock bottom. On March 5, 1977, he suffered a minor heart attack. He had to crawl half a mile out into the road for help. While he recuperated, his brother Joe stood in for him during some long shots, and Martin returned to the film a few weeks later. Soon after, Marlon Brando arrived...

Ending Woes

When Marlon Brando finally arrived in Manila to complete his portion of the shoot, Coppola was upset to discover he was overweight. The director combated the problem by dressing Brando in black and only filming his face. Meanwhile a taller actor doubled for him to give him more height.

“My Kurtz was a man who saw the truth,” screenwriter Milius says of how he wrote Kurtz. “He was mad, but he saw the truth. He was destroyed by the truth, burnt out by the truth.”

Together, Brando and Coppola attempted to craft a decent ending for the film. But as Coppola struggled with the task during a hiatus from shooting, disaster struck – Brando was threatening to keep his $1m advance and drop out of the film altogether.

“Are they seriously saying Marlon would take a million dollars and then not show up?” Coppola is seen stressing in making-of doc Heart Of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse . “Imagine here I am with about 50 things that are quasi in my control, like the Philippine government and the helicopters that they take away whenever they feel like...

“All I’m asking is for people to allow me to start a little later, and I know it’s all my fault. The picture’s bigger than I thought, it’s just gigantic.

“I personally, as an artist, would love the opportunity to finish the picture up until the end, take four weeks off, work with Marlon, re-write it and then in just three weeks do the ending. I think I could make the best film that way.” For Brando’s representation and the studio, though, postponement wasn’t an option...

Postponement

Coppola, understandably found the whole situation interminable and excruciating. Still on the phone in Heart Of Darknes s, he lets the studio know exactly how he feels.

“I feel like people back there feel like, uh-oh postponement, the picture’s in trouble,” he says. “This is a very intelligent major studio, you think like this all the time...

“What bugs me is the ludicrousness of thinking that I’m gonna go through all that I’m doing, after all I’ve been through in the past, after all the pictures I’ve made, that after 16 weeks I’m not gonna finish a movie in which I’ve invested three years of my life. It’s stupid, man.”

He adds confidently: “Even if Brando drops dead I can still finish the movie. I’ll just get an actor. If I can’t get Redford, I’ll go back to Nicholson...”

Final Months

Filming trundled on, though, and Brando never delivered on his threat. Dennis Hopper arrived to film his part, and recalls the final months of the movie as being equally as tumultuous as the first.

“I was there for four or five months,” he said during an interview. “When I arrived I was signed to play a CIA agent. There was no script. So I started out in a clean uniform being told by Francis that I was going to be second-in-charge to Marlon Brando’s army he had in the jungle.”

In the end, Hopper and Brando never even met on set. “He’d shoot one night, then I’d do another. I came in one night and Francis said, ‘Marlon called you a “snivelling dog” and threw bananas at you.’ So I had this prop man throwing bananas at me all night long. In the end, it worked out really well.”

After a shoot that spiralled out to last a whole year, heart attacks, weather disasters, unreliable actors and an ever-evolving script, principal photography on Apocalypse Now finally wrapped on 21 May, 1977...

Cannes Calling

“When I got back, people said, ‘Oh, this film's a disaster, it's unreleasable,’” Coppola remembers. “We weren't really quite finished with it, but I thought the only way to protect myself was to take it to Cannes unfinished and just show it, and try to let the film speak for itself.”

Coppola screened an unfinished version of Apocalypse Now in America in April 1979. The screening received a negative response. But an invitation from the Cannes Film Festival piqued Coppola’s interest – especially considering the filmmaker had previously won the Palme d’Or there with The Conversation.

“At Cannes, I tried to explain the experience itself,” says Coppola, “my going there, putting everything on the line, mortgaging my house, making this film, going through countless difficulties, was an experience almost like Vietnam. My experience making it was a metaphor for the war itself.”

When a three hour version of the film screened at the festival as a ‘work in progress’, it was met with rapturous applause. It went on to win the Palme d’Or, a victory that must have made all the struggles and difficulties almost seem worth it.

Boosted by that success, Apocalypse debuted at the US box office in August 1979 and ended up making an impressive $150m worldwide. Influential critic Roger Ebert commended the film for achieving “greatness not by analysing our ‘experience in Vietnam’, but by re-creating, in characters and images, something of that experience”...

Redux

An extended version of Apocalypse Now , entitled Apocalypse Now Redux , was released by Coppola in cinemas and DVD in 2001. This new edit of the film added 49 minutes of extra footage that was shot but then excised from the ‘79 theatrical release.

“I always like to say the abstract art of one period becomes the wallpaper a few years later,” Coppola says of the release. “And I thought, gee, that original version had a lot of stuff that we liked but we took out.

“And really, people had said, ‘What happened to the French plantation?’ So we just basically put it back. And the Redux version was nothing more than the original version as it had been before we shortened it for the release.”

The added footage included a lengthy encounter between Willard and the de Marais family at their rubber plantation, a scene in which the soldiers spend time with the Playboy bunnies, Kurtz reading Time magazine to Willard, and a little surf board thievery...

Apocalypse Again

Apocalypse Now is back in cinemas this week. Now preserved in the American Film Institute as a work of cultural significance and importance, it’s often heralded as the defining war movie of its time.

Why is it such an enduring vision? “It goes to this element of risk,” Coppola muses. “When movies are made, especially today, they eliminate the risk factors to such a great extent by predigesting the movie and applying what they think are rules learned from successful films.

“The investor dominates the process. And so the films don't have complexity and depth. Clearly [Apocalypse Now] went off on its own to explore the themes of what was a very unusual, maybe unprecedented, war on many levels. So when the film came out, it shocked people at first and almost defied them, because it was so different than what had been considered a war film.”

As Coppola famously said during a conference in Cannes, “My film is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam.”

Josh Winning has worn a lot of hats over the years. Contributing Editor at Total Film, writer for SFX, and senior film writer at the Radio Times. Josh has also penned a novel about mysteries and monsters, is the co-host of a movie podcast, and has a library of pretty phenomenal stories from visiting some of the biggest TV and film sets in the world. He would also like you to know that he "lives for cat videos..." Don't we all, Josh. Don't we all.