The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask: Inside the surrealist sequel that was never supposed to exist

How Nintendo achieved the impossible: Following up on the iconic The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time

The strict time constraints and constant pressure of Majora's Mask mirror perfectly the creation and development of the game itself, completed in just one year. After 1998's Ocarina Of Time became an instant hit and redefined 3D gaming, series producer Shigeru Miyamoto wanted to both capitalise on its success and further utilise the game's engine; the iconic title originally used the same engine as Super Mario 64, but so many modifications were made during Ocarina's three-year development that it became its own beast.

The spawning of a sequel ties in heavily with the failure of the 64DD, a Japan-only peripheral designed to expand the limitations of the Nintendo 64. Ocarina Of Time was intended to be a flagship title for this new device, but Link's expansive range of motion was stunted when the game was read from a disc, thus the code found its home on a 32-megabyte cartridge instead. However, this halved the available space, meaning many concepts, enemies and locations went unused in the final release.

The 64DD suffered repeated delays and was still under development at the time of Ocarina's launch. Holding onto the hope that this future technology would find its footing, plans were discussed to bolster Ocarina Of Time with a disc expansion. The story would remain the same, but the overworld would be flipped, enemies would hit harder and dungeons would be relocated and redesigned to pose new challenges for returning players. Inspired by the Second Quest mode unlocked after completing The Legend Of Zelda, it would ensure that the engine and cut content wouldn't go to waste.

You're a Zelda

Most of the work of overhauling the dungeons for the 64DD expansion, tentatively titled 'Ura Zelda', would fall to Eiji Aonuma, lead dungeon designer for Ocarina Of Time and one of its directors. Going back to the drawing board, Aonuma became frustrated. He'd spent a lot of time balancing his dungeons with puzzles, exploration and combat, and believed his creations were already the best they could be. He found himself designing new dungeon concepts instead of remixing his previous work, getting more enjoyment from his secret side project.

Inspired, Aonuma built up the courage to meet with Miyamoto to present his ideas, asking if they could instead work on a new Zelda. Miyamoto agreed, but with one caveat: the game must be finished within a year. It could make use of Ocarina's engine, assets, models and unused material as a way of speeding up production, but would need all-new dungeons, story elements and quests, as well as some fresh mechanics. Aonuma cautiously accepted the mantle of supervising director of a new Zelda story, and the race against the clock began.

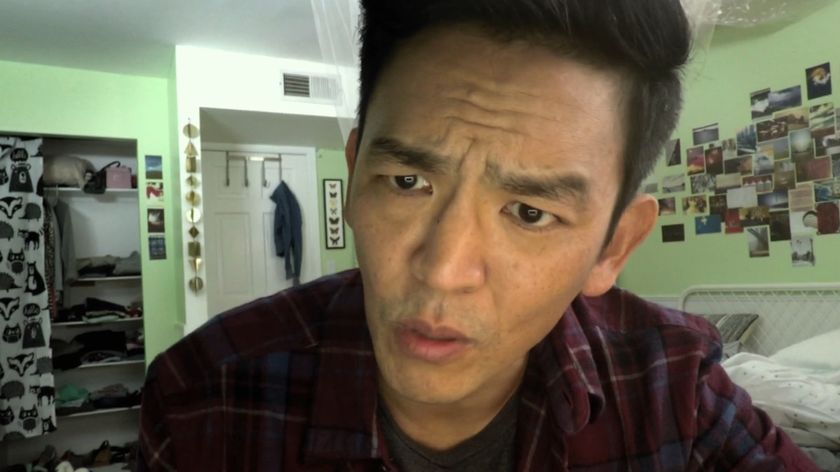

Development started in January 1999, just two months after Ocarina's release. With a much smaller team and limited to a third of the time its predecessor had required, Aonuma needed an ambitious idea to continue the legacy of what was being called the pinnacle of game design across the world. Wondering what kind of game could find success as a follow-up to something so critically acclaimed, Aonuma conferred with fellow Ocarina Of Time director Yoshiaki Koizumi. Koizumi had worked on story elements for A Link To The Past and created the ethereal dream world of the Wind Fish for Link's Awakening. Aonuma hoped he could help with ideas for the new game, given the working title of 'Zelda Gaiden', meaning 'side story'.

At the time, Koizumi was in charge of his own project, a cops-and-robbers board game where the aim was to catch a criminal in under a week. Though this game would never come to fruition, its soul can be found at the heart of Majora's Mask.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Day and night

Taking inspiration from his board game, Koizumi agreed to work with Aonuma on Zelda as long as the passage of time was a key element. Since Ocarina Of Time already had a day-night cycle, which could even be controlled by the player with the Sun's Song, the foundations were already in place. The pair realised that a week-long time loop could pack a lot into a compact game world, adding depth over breadth. Playing the same days over and over while uncovering more and more secrets was the genesis of a new form of exploration, relying on multiple playthroughs. At the end of a cycle, you'd have to go back to progress forward. Miyamoto approved of the concept, liking how it added replayability.

Zelda Gaiden had its core element, and because the series had already featured time travel, it didn't feel out of place. Now it was time to build around that. Taking Link away from the well-travelled Hyrule, the parallel world of Termina gave new stories and personalities to the familiar faces borrowed from Ocarina Of Time, with these doppelgangers adding to its otherworldly feel. Koizumi would build a bustling town, focusing on realistic depictions of the lives of the townspeople, all busy going about their day. Aonuma would design the overworld, with each cardinal direction given a different theme that tied into its dungeon and populated with different races and creatures.

At first, Termina's stories unfolded over a week of in-game time, but Aonuma and Koizumi realised that keeping track of schedules and events was too complex when spread across seven days. They were concerned that players wouldn't want to spend days waiting for a specific event to reoccur after travelling back to the start of the week. Seven days was pushed down to three, but the story and events were compressed into three days as well, forging a tightly packed world with a lot of substance. Only having to work with three days of content shortened the development time, a huge boon for a small team with a time limit.

Majora's Mask is both hailed and hated for being as stressful as it is enjoyable. Having just three days of play piles on the pressure, compounded by the many clock faces around Clock Town and the timer ticking away on-screen at all times. A fear of the passage of time is intrinsically human, conscious of our own mortality, the limited time we have and what we do with it. Time in Majora's Mask is utilised in such a way that you're constantly fighting against it – not just monsters and demons – and even though you alone have the power to turn back time, progress is lost and the clock simply starts winding down again. No one can escape time; it can't be defeated. This adds a sense of futility to the hero's journey – no matter how powerful Link becomes, he'll never be able to stop the march of time or help everyone in Termina in one cycle.

As if this isn't harrowing enough, the moon is about to crash into Termina. Time is running out for its residents, and they slowly come to terms with this over the course of the game. Upon your arrival, the people of Clock Town begin to question if it's really happening, some fearful and others in denial. With each passing hour, the falling moon becomes larger in the sky, and the atmosphere of the town changes. Fewer people go out in the streets. They'll mention their growing fears as they confront the end of the world in their own ways. By the Final Day, Clock Town is eerily empty. Those who remain quiver in fear, deny their destruction or accept their fate.

The moon falling was another of Koizumi's ideas, coming to him in a daydream. Gazing up at the sky, he wondered what would happen if the moon were to fall towards Earth and how people would react to this apocalyptic event. With a sense of impending doom a perfect fit for a game with time at its centre, the main story and side-quests were designed around a world about to meet a terrible fate. Though early concept art showed a moon with no features, the final version's pained expression adds further discomfort, constantly looking down on Link with those haunting eyes as he makes yet another attempt to stop its deadly descent. And here the hero can fail. Without player input, the world still progresses, the moon growing ever closer, the clock ticking away. The Final Day ends, and the world with it in a fiery blaze.

The downfall is depicted beautifully in Koji Kondo's soundtrack. Clock Town has a different arrangement each day. It starts cheerful and joyous, the town still gearing up for the festivities. By the Second Day, uneasiness has crept in. The pace has picked up and fewer instruments are featured. The tones of the ocarina stand out against the more muted backdrop. There's a slight sadness to it, especially against the rainfall. On the Final Day, the pace is frantic. There's a sombre string motif behind it that compounds feelings of anxiety – something about it doesn't sound right. But it's the music in the Final Hours that's truly chilling: slow, sorrowful strings that pull at your heart as you wait for it all to end.

Dark and despair

Ocarina Of Time had dark moments, but can't compare to the despair, distress and desperation woven throughout Majora's Mask. While designed for returning players – hence the complete lack of a tutorial – the sequel levels the playing field by ripping away everything that made Link special. You begin the game absolutely powerless: a lone child lost in the woods, robbed and cursed by a mischievous imp. Though memories of Hyrule make this all the more impactful, Zelda veterans will feel just as lost and confused in a new body and a new world. Adjusting to his transfiguration into a Deku Scrub, the fallen hero soon finds purpose upon meeting the Happy Mask Salesman, who offers a deal Link can't refuse.

Opening the doors of the Clock Tower to uncannily familiar faces in an unknown setting, it sinks in that you're a foreigner in this land. Link was destined to save Hyrule, but in Termina, he's simply passing through. Exploring the ill-fated Clock Town, you'll find that people are too preoccupied with their own anxieties to give you much consideration, especially while you're trapped in a childlike wooden body. Even after you regain your true form, not many people outright ask for your help. You infer their troubles and simply decide to help because it's the right thing to do. You want to see if you can help… to heal this cursed world.

It's apt that Clock Town runs like clockwork. Everyone sticks to their schedule unless you choose to intervene, but you have to be in the right place at the right time, sometimes needing a specific item or song. If you miss or fail an encounter, you'll have to take what you've learned and try again. Interacting with some of the citizens is entirely optional, though there's a lot to gain from helping them – and not just through rewards. Majora's Mask's many sidequests expand its small world exponentially. Exploring the personal stories gives you all the more reason to save Termina because these characters feel real: they have fears, hopes and feelings. Koizumi built his real-life experiences into them, giving them heart. You can also be confronted by the consequences of your inaction, guilt spurring you to want to help next time around.

To experience the full spectrum of emotions here, you'll need to collect masks – an element that was present, but not fully realised, in Ocarina Of Time. In Termina, masks are given deeper meaning and grant a host of abilities. While some citizens of Hyrule would react to Link wearing different masks, here he uses them to elicit the feelings of others and break the many curses afflicting the land. Each mask Link receives is bound with the feelings and memories of the person who entrusted it to him, reminding him of those he aided even when he returns to a time before he solved their problems.

The three transformation masks contain the very essence of a departed soul. Link soothes the restless dead with his song, allowing them to move on. Wearing the masks they leave behind, he's flooded with their regrets, of things they didn't manage to accomplish in life and the friends they left behind. He takes up the mantle of the deceased, vowing to right the wrongs they failed to fix in their stead. Transforming into shades of their former selves, he selflessly saves each corner of Termina while wearing another's face – once again, Link won't be remembered as the hero. Each race is liberated by its own masked champion, but because of this, none of them realises they've lost someone dear to them.

Growing pains

"Pain and loss are found wherever you go in Termina."

Pain and loss are found wherever you go in Termina. The Southern Swamp of the Deku is toxic and its princess is missing. Snowhead is trapped in an eternal winter and the Gorons are freezing to death. Great Bay is under threat from climate change and Zora-egg-stealing pirates. Ikana Canyon is a place cursed with undeath. In each direction from the terminal that is Clock Town, there are self-contained problems to solve on top of the threat of the moon. Navigating each locale successfully will require you to master your masks, seamlessly blending in with the people who dwell there and gaining their trust in order to access their sacred temples.

While Majora's Mask only has four major dungeons, reaching them is a challenge in itself, preparing you for the puzzle themes you'll discover within. All four are masterfully crafted, making excellent use of three-dimensional space. You'll need to understand the very architecture of the temples, with a good grasp of spatial reasoning required to best them. Exploration is key, traversing interlinking rooms and learning the layout, but doing so against the clock makes it all the more difficult. Woodfall requires mastery of Deku Link. Snowhead needs you to visualise how each room connects to the central pillar. Great Bay has you paying attention to pipe colours and changing water currents. In Stone Tower, you must map out both the floor and ceiling, but it also tests you on your transformations, bringing together every part of your journey.

Though it would have been easy to follow Ocarina Of Time with another heroic tale, the courage of the team to try new ideas and weird concepts ensured that the game was far from a cheap imitation, and that it was compiled in a year using borrowed assets makes that all the more impressive. Majora's Mask certainly stands out as a black sheep of the series, with not even Twilight Princess coming close to its level of darkness. It's a divisive entry, with many complaining about the punishing difficulty and focus on side stories, but it has gained a cult following from those looking for a little existentialism in their adventures.

What's so captivating about Majora's Mask is the many mysteries it leaves behind. Even after multiple playthroughs, you're still left with questions you'll never get an answer to, daring you to come back to the game to see if you can finally uncover all of its secrets. It's the kind of game that will occupy your mind for years after you put down the controller, be it in frustration or completion. But whether your parting with the game is forever or simply for a short time… that is up to you.

Keep up to speed with all of our celebratory Zelda coverage with our The Legend of Zelda celebration hub

10 years later, in a post-Baldur's Gate 3 and Avowed world, Obsidian is giving its own throwback CRPG Pillars of Eternity a turn-based combat mode

This cozy RPG promises a Pokemon and Stardew Valley mashup with "limitless customization," 208 monsters, and more, so no wonder its Kickstarter was funded in just 16 minutes