The genius of Metro: Last Light isn't the shooting, its the sad portrayal of post-apocalyptic life

There are few feelings as comforting as arriving at a station in the post-apocalyptic Moscow Metro, the blast doors groaning shut behind me to block out the ungodly mutant shrieks reverberating through the decrepit, varicose tunnels. Inside these stations, people stoically get on with their lives in corrugated subterranean shacks – trading, working, drinking, procreating – giving a powerful sense that, even when things are at their very worst, humanity grits its teeth and powers on.

- The best Xbox One exclusives - the games essential for your console

- Every Xbox One X enhanced game - 4K, HDR, frame rates & more

To an extent, the above scene could be from either Metro game, bespeaking the lack of significant evolution between 2033 and Last Light. The mechanics are identical and the plot is a direct continuation, as mute protagonist Artyom must track down the last remaining survivor of The Dark Ones – the telepathic species he wiped out at the end of 2033. But while Last Light may lack raw ambition, it does an incredible job of amping up the atmosphere and world-building.

Walking through the enclaves of humanity in Last Light is essentially a monorail ride, a single path with a clear destination, except you can jump off when you please to go into a bar, back alley or brothel, where you’ll encounter some wonderfully scripted vignette or conversation giving you insights into the day-to-day rigours of life in the subterrane. The station of Venice, for example, is essentially a fishing town. Kids play with toy boats in the sickly waters while men fish next to them, traders sell dubious looking sea-creatures, and I buy an awkward lapdance before getting blackout drunk (returning later to find a ruined bar, bloodied floor and crying barman). Bolstered by the naturalistic dialogue (co-written by author of the Metro novels, Dmitry Glukhovsky), Last Light feels incredibly human.

Kids play with toy boats in the sickly waters while, traders sell dubious looking creatures

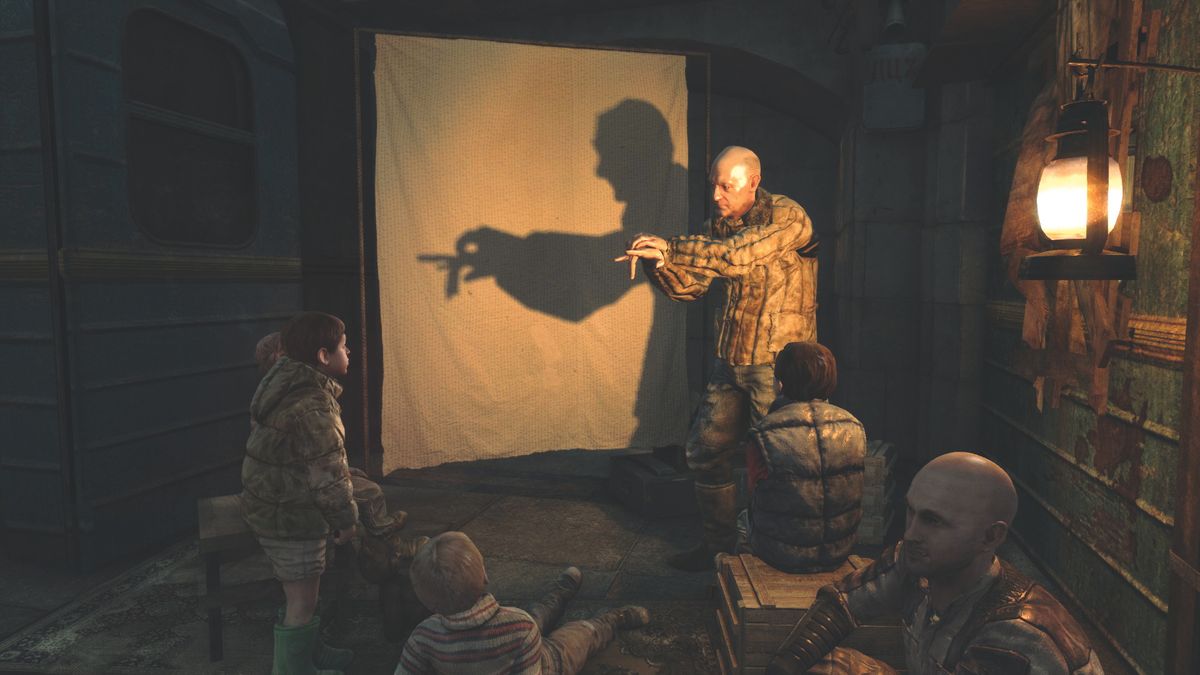

At Bolshoi, the cultural heart of the Metro, I stop to watch a man tell children about animals that used to exist on the surface, depicting them using hand shadow puppets. I then give a bullet (the pragmatic currency of the Metro) to a beggar, and discover that he was actually a respected critic before the bombs fell – a stern reminder that middle-class softies like yours truly aren’t cut out for the post-apocalypse, much though we like to fantasise about ‘What We Would Do’ should it occur.

There’s a good reason I’m talking about everything I did outside of combat in Last Light, because there’s least to say on that front. Stealth is flimsy, and usually ends in a generic firefight against shonky AI, while encounters are either waves of mutants or cover-filled rooms of soldiers. It’s dated, but there are some great touches, such as the air-pressurised gun that you need to pump to deliver maximum damage, and the gas mask that you keeps you alive on the surface, which gets smeared with perspiration and blood that you can wipe away to create an aptly suffocating sense of claustrophobia.

With Metro Exodus on its way, everything from the title to the trailer suggests that the underground won’t play as big a part this time round, and that’s fine. The backdrops on the surface in Last Light teased a stunning broken world screaming to be explored, and one mission, where you ride a kart down a Metro track and can jump off at any point to explore numerous side-rooms, hints at the exploratory potential in a fully open underground network.

But while a free-roaming post-apocalyptic Moscow is alluring, can the urban centres have that same rich character when you can freely visit them over and over? Will humanity living on the surface have the same air of impressive resilience as when it lived underground? Paradoxically, Exodus’ biggest challenge will be to pull us deeper into this fascinating world so well evoked by its predecessors, rather than push us out onto the surface.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Rob is a freelance games journalist, SEO and content manager. He's written for PC Gamer, GamesRadar, Kotaku, Rock Paper Shotgun, WhatCulture, NextPit, PCGamesN, VG247, Eurogamer, TechRadar, and more.