The Fly’s journey to the screen began in the early 1980s, after screenwriter Charles Edward “Chuck” Pogue had returned from England, where he had just written two Sherlock Holmes films, starring Ian Richardson. Pogue hooked up with a young producer named Stuart Cornfeld, today co-producer and business partner of Ben Stiller.

They pitched Twentieth Century Fox a remake of The Fly, a 1958 B-movie starring David Hedison (later to play Felix Leiter in Live And Let Die and Licence To Kill) and horror icon Vincent Price. Beginning with the mysterious death of a scientist in a hydraulic press and his wife’s confession of murder, the film uses flashbacks to tell the tale of a terrible science accident that transforms its hero into half-man, half-fly.

Pogue was under no illusions about the movie’s shlocky status. “It was kind of bad science, as well as bad drama,” he tells SFX. “The guy goes through the transporter and comes out with this big fl y head. What you’re left with is a passive hero. He’s got no facial emotion and no voice; he’s reduced to scrawling words on a chalkboard. Because of that choice, the film shifts to following the wife’s descent into madness.”

“The original version of The Fly was kind of a camp classic,” Cornfeld agrees. “It had the scene with the little fly with a man’s head at the end, going, ‘Help me! Help me!’ The original movie gave our version a little familiarity, but it also made it a lower prestige movie. It definitely wasn’t a case of people saying, ‘Ooh, they’re remaking The Fly, this is going to be a prestigious production!’ A lot of people were laughing at us.”

If they were laughing at first, nobody laughed when director David Cronenberg was announced as director. Cronenberg was the perfect filmmaker to helm The Fly. In his early forties, he had already established a suitably twisted “body horror” oeuvre which included movies like Shivers and Scanners.

"We were told that hiring Jeff Goldblum would be a big mistake."

Stuart Cornfeld

Although he had yet to score a monster-size hit, Cronenberg was considered bankable by Hollywood studios: he was offered such disparate projects as Total Recall, Beverly Hills Cop, Flashdance and Top Gun during this time period. The Fly sat particularly neatly alongside Cronenberg’s previous two films, Videodrome and The Dead Zone, both of which concerned a male protagonist who becomes wrapped up in horrific events which profoundly alter them.

If anything, The Fly was a distillation of the themes from these two movies: in the movie, both the origin of the horror and its terrible consequences come from the protagonist. There is no outside agency or villain to blame. The Fly is Cronenberg at his most tragic. All of which makes it all the more surprising that he wasn’t the first filmmaker to take on the project. British television director Robert Bierman was hired, only to drop out. “Robert ended up suffering a [personal] tragedy,” Cornfeld says.

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

“It wasn’t a proprietary thing, but he had a take on it that was very different to what Chuck and I had been developing. He liked the premise of what we were doing, but our script was not as interesting to him as what he had going on in his mind.”

One major concept Cronenberg got rid of was the notion that the two central characters should be married. This was a hangover from the 1958 original, but something Pogue had also felt was key to the story. “My rationale for that was that you needed that kind of emotional connection for them to stay together while he is going through his awful transformation,” Pogue says.

Cronenberg also amalgamated two of Pogue’s characters into one, along with changing the name of protagonist Geoff Powell to Seth Brundle, named after Formula One racer Martin Brundle. What he retained was Pogue’s concept that the entire film should be about the metamorphosis of man into fly, rather than making it an immediate transformation.

“Cronenberg has always been very generous in saying that he couldn’t have got to his version without my version,” Pogue tells SFX. “He kept the claustrophobic tone of my script, but maybe even heightened it further.” Under Cronenberg, the production’s shooting location shifted to his native Canada, while he brought on crew members like cinematographer Mark Irwin, with whom he had worked before."

“We shot for ten weeks in a warehouse that was meant to be Brundle’s lab,” recalls Irwin, who had the exciting, yet challenging, task of making what was basically a one- location movie visually exciting. “I realised that the room had to become a character in the movie, just like the people. I made it get darker and change progressively and become more mysterious throughout the story as Jeff’s character goes through his change.”

In addition to Irwin’s photography, Cronenberg’s direction, Howard Shore’s ominous music and the Academy Award-winning make-up effects, one of the best- remembered aspects of The Fly is the tremendous lead performance by Jeff Goldblum. Still best known as a character actor, The Fly represented Goldblum’s leading man debut. Not everyone necessarily approved. Twentieth Century Fox president Larry Gordon was particularly sceptical – although he gave The Fly’s crew the benefit of the doubt.

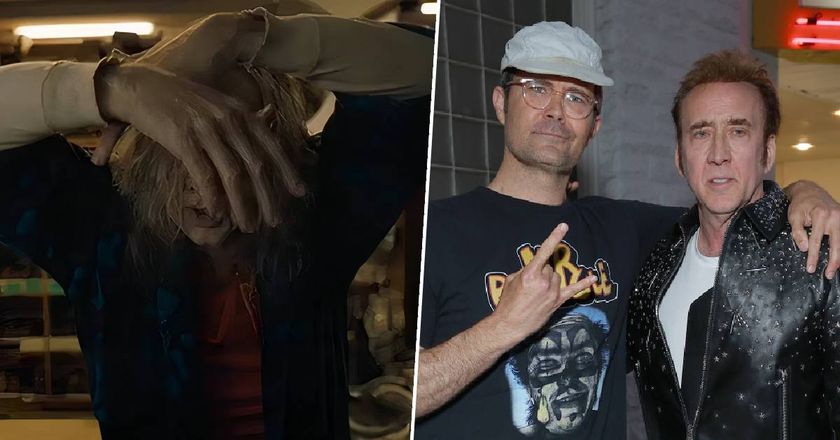

“Cronenberg and I went to him and said we wanted Jeff Goldblum to be the lead,” Cornfeld says. “Larry Gordon thought that was a horrible idea. He said to us that hiring Jeff would be a big mistake. But he said, ‘It’s your mistake to make. If that’s who you want, go make your film with him.’”

Goldblum’s eventual performance blew everyone away. Mark Irwin recalls how the movie was shot in order, and Goldblum isolated himself as his character went through its metamorphosis: requiring more and more latex to be applied each day. “Jeff’s a talented pianist and we had a piano on set,” Irwin says. “Early on he would entertain everyone by playing between takes. Later on, as he got more into the rubber suit and the transformation into Brundlefly, he stopped playing and became far more introspective.”

In its most extreme stages, the Brundlefly costume Goldblum had to wear took 10 hours to put on and a further six to remove. Playing opposite Goldblum as his love interest was actress Geena Davis, who married him in real life the year after the film was released. The chemistry between the two is palpable on-screen. The fact that the romance works so well is the emotional beating heart of The Fly, just as Chuck Pogue hoped it would be.

“The jeopardy in The Fly is not about the protagonist turning into a creature, but that love is being lost,” Mark Irwin says. “The fact that it ends with Geena’s character putting a shotgun to Brundle’s head to murder him, so they can both find peace... well, that’s David’s own personal twist on things.”

The Fly arrived in cinemas in August 1986. Helped by its iconic tagline “Be Afraid, Be Very Afraid” (suggested by Hollywood legend Mel Brooks, whose company produced the movie), it proved an immediate hit with audiences. Despite not working on the entire film, Chuck Pogue was happy with how it turned out.

“What’s always made me proud was when people talk about how it transcended its genre,” he says. “I always thought about it as being much more than a monster movie, and it’s great to hear that people agree. I felt it really resonated.”

Pogue’s next job was writing a second Psycho sequel, another movie which came out in the summer of 1986. A reviewer for an alternative Los Angeles newspaper, The LA Reader, wrote an article about his picks for the best two love stories of the summer. He chose The Fly and Psycho III. He neglected to mention that Pogue was the connection between both. Pogue was later asked to write the script for The Fly II, although he turned it down. “I really didn’t like their take on it,” he admits.

Like the best horror movies, tapping into why The Fly worked so well is difficult. It appealed to the same science-gone-awry technothriller sentiment that turned Jurassic Park scribe Michael Crichton into a bestselling author. It featured great special effects that appealed to the horror crowd and a human story that made it a weird kind of date movie. There was even an Aids metaphor hidden not too deeply under the surface, which meant the film plugged into a certain terrible zeitgeist.

“Horror is great, because as long as you fulfil the basic obligation of the genre – to scare people – you’re really free to do whatever else you want,” Cornfeld says. “In a weird way, filmmakers have more autonomy in horror films, and comedy to a certain extent, because the primary thing the studio is interested in is whether it’s a scary horror film or a funny comedy.”

Ultimately, Cornfeld doesn’t want to dissect what made it special any more than he did his other favourite horror movies The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby.

“Honestly, I was just a believer in the thing,” he says. “I thought people were going to show up and they were going to like it. I’m glad it’s gotten the reputation it has, but I was never trying to second-guess the audience. I just assumed they were just like me – and I was really into it.”

This feature originally appeared in our sister publication SFX magazine, issue 281. Pick up a copy now or subscribe so you never miss an issue.

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.

Most Popular