The changing faces of the big three

Who got better, who got worse and who screwed it up completely

"Famicom" is an abbreviation of "Family computer", and with that naming convention came Nintendo's outward manifesto for more than the first two decades of its life as a games company. Under pre-Iwata president Hiroshi Yamauchi, Nintendo put across a staunchly innocent image, pushing family values and overall pleasantness to the fore.

In fact, it went so far as to become an official content policy for licensees wanting to put out games on any on Nintendo's machines. Graphic violence, nudity, blood, drugs, politics and religion were outlawed, and while it meant that the company probably threw crap parties, for a good while it was a situation that suited most gamers just fine.

Ironically, it suited Sega down to the ground too, as Ninty's clean living approach gave its biggest rival a very obvious angle to exploit with its own marketing during the '90s. Nintendo was the puritan, Sega was the cool, chain-smoking biker kid. Mario was fat, friendly and safe, Sonic was cool, edgey and badass (ignoring the fact that he was a primary coloured rodent traditionally known for getting run over a lot).

Regardless, in the more innocent early ages of gaming when everything was shiny, new and still largely only adopted by "the kids", Nintendo's image was just fine. Yamauchi and US boss Howard Lincoln presented a fairly sensible yet enthusiastic front at industry shows, backed up by some guy called Miyamoto who popped up from time to time to show off the new games he was working on. Nintendo's ads were the traditional mix of '80s "cool" and bizarro weirdness that typified the period.

Come the mid '90s, Nintendo was hitting a snag. While its games continued to be the finest, freshest and most inventive in the industry, the kids were growing up (a bit) and becoming ever more tempted by Sega's dark world of rebellious vice. It all came to a head with the infamously censored SNES version of Mortal Kombat, which bombed in sales compared to Sega's bloody Mega Drive version. It was a major coup for Sega, and fanboys on both sides were so wrapped up in how much Nintendo's traditional values had held it back that barely anyone seemed to notice that the game was a piece of crap. This is where we finally started to see a shift in Nintendo's presentation of itself. Gore was allowed in MKII, but the real statement of intent came with Killer Instinct.

Not only was Rare's arcade game the most gleefully violent fighter to date, reveling in blood and boobs for gratuitously comic effect throughout, it was actually the game that Nintendo chose as the first glimpse of its next-gen N64 technology. Well, in theory anyway. We all know how that turned out.

But from then on, the floodgates were open. Nintendo formats were as accessible to mature content as any other, and from the late SNES period onwards we got the likes of Doom, Duke Nukem, Resident Evil 2, Turok, Shadowman, and by the time of the Gamecube, Nintendo was actually courting companies like Silicone Knights and Capcom for properties like Eternal Darkness and Resi 4.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

For all of that though, Nintendo was still rigidly old-school in a number of ways, refusing to pick up the multimedia technology, optical storage, hard-drives or online connectivity of Sony and Microsoft. Yamauchi repeatedly explained to the press that he wanted Nintendo to remain purely a games company, and Lincoln concurred, stating that "Nintendo is a gaming company. It is not a consumer electronics company, and it is not a computer company. We design with games in mind, and not anything else." Ironic how things have changed, no?

It's 2004. Nintendo is now seen as an anachronistic old dinosaur, so mired in Yamauchi's traditional values and policies that it has half-drowned in the modern age of gaming. Where its rivals have showboated their maturity and coolness at every opportunity, Nintendo has stayed quiet, pleasant, modest and understated. Many expect it to slip away unnoticed before long.

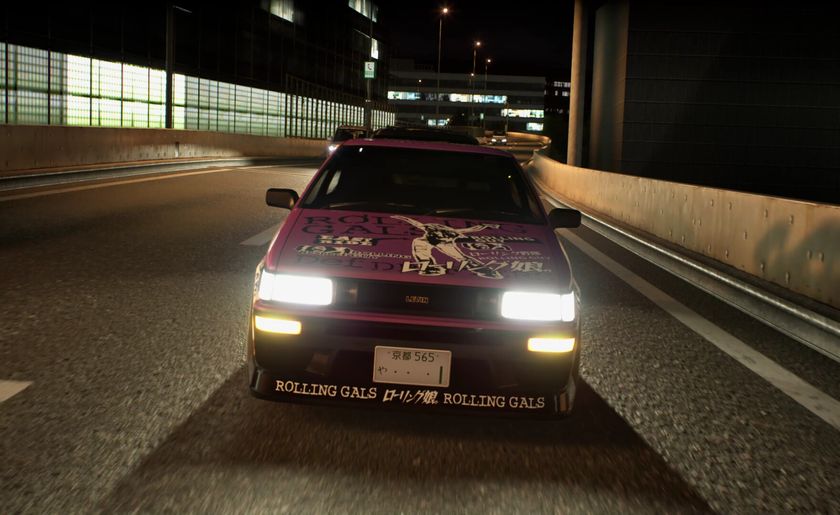

At E3, all of that changed. A man carved from a 10 ft slab of meat burst onto Nintendo's press conference stage, seemingly ready to punch half of the audience into unconsciousness and use their rendered bodies as clubs to knock out the other half. Apparently, he was quite into both kicking asses and taking names.

Lincoln was gone, as was Yamauchi, and we now had the younger, more dynamic team of Reggie Fils Aime and Satoru Iwata. This new Nintendo was more than happy to talk about how great it was, how much better it was going to be, and how much forward-thinking it was compared to its competitors. Yeah, forward-thinking. It couldn't have been more different.

Box-exterior-located ideas came thick and fast, led by the multi-use innovation of the DS, a device that was billed as being good for everything from 3D gaming to PDA applications. This Nintendo was about a true evolution of gaming technology, and it promised to shake up traditional console gaming in a way no-one had ever seen before with its next home machine. And when the nature of that console was revealed a year later, Nintendo of course used it to emphasise just how progressive it was, not only from its old self, but also from everyone else in the industry.

With the Wii still selling by the planetload regardless of a dearth of actual games, Nintendo's E3 2008 show took a whole new focus. Nintendo was now a lifestyle business, selling an ideal rather than a product, and it was making too much money out of that aspirational image to waste time on the traditional games of old. Thus, game announcements were replaced by endless photos of old people waggling Wiimotes and the badass "We're going to own gaming" spirit of '04 gave way to an insipid and fairly abstract desire to make people smile. Presumably people who REALLY like digital cookery books.

It says it all that Nintendo's traditional red logo has now been officially replaced with a grey one. This current iteration of the company is all about a vague spirit of togetherness, expressed through a slightly disturbing fervour for its Wii-led utopia, but without any real tangible reason for it. It's all about oneness, sharing and family interaction, but not about cool or fun. Reggie is more restrained, Cammie Dunaway simpers away with saccharine enthusiasm about how much her son wubs dat mommy works at Nintendo, and Miyamoto is just wheeled out as an embarrassed-looking dancing monkey reminder of the games he made for the SNES.

In the 80s it seemed implausible. Now it's fact

Life moves pretty fast sometimes – but videogames move faster. Here’s the proof