Why you can trust 12DOVE

To life’s many great imponderables – Where did we come from? What’s our purpose? Does God exist? Why did they make a fourth Scream movie? – we can now add the following question: would watching The Beaver without any awareness of Mel Gibson’s monster raving loony antics make it a better film?

Unfortunately, it’s a question that can never be answered, which is a shame for Jodie Foster, whose third film as a director (her first in 16 years, since 1995’s enjoyable if lightweight Home For The Holidays) arrives tainted by the sour s(mel)l of scandal.

Maybe a few lost Amazon tribes can one day experience her tenderly sculpted dramedy entirely free of prejudice, but for the rest of us it’s like an annoying gnat buzzing round your ear, getting louder at the most inopportune moments.

So, that’s something of a bummer. Surely, though, any seasoned moviegoer should be able to block out megastar baggage, but be honest: have you been able to watch a Tom Cruise film in the same way again since he jumped the couch? What ends up surprising about The Beaver, then, is actually how sad and moving Walter Black’s plight plays out on screen.

That’s a testament to Foster’s laser-guided commitment to exploring clinical depression’s unfathomable ache, and also to Mad Mel himself, who nails his character’s anxious mania and soul-squashing despair in a way that never feels cheap.

It’s a dark, powerful, haunted performance. You could even argue that Gibson’s vile rants enhance its intrigue. He’s a man plagued by ugly demons playing a man plagued by ugly demons – looks like Foster knew exactly what she was doing when she invited her Maverick co-star and friend to the Beaver house.

Fist of furry

Lost in a black hole of worthlessness despite his surface-perfect life, Walter finds the eponymous grubby puppet in a dumpster, and surrenders himself to it following a suicidal bender that ends with him waking up in a motel room doing a Ray Winstone impersonation: “Ahm The Beavah and ahm ‘ere to save your Goddamn life.”

From that point the surprisingly emotive hand-rodent is never off Black’s mitt, allowing him to bond with his young son (Riley Thomas Stewart) over woodcarving, romance his compliant wife Meredith (Foster herself) and revitalise his moribund toy company. Uh-huh… and if you buy all that, then we’ve a nice pyramid money scheme to interest you.

Kyle Killen’s script, which once sat atop the Black List of great unproduced screenplays, trades in cutesy fable. But if you stomach its implausibilities (Winter’s Bone Oscar nominee Jennifer Lawrence as a valedictorian cheerleader who, in her spare time, happens to be a gifted graffiti artist? Please...) there are acres of barbed, witty insights, puncturing America’s over-reliance on pills, self-help manuals and Oprah Winfrey.

The only person petrified by The Beaver’s arrival is Walter’s older son Porter (Anton Yelchin). It’s unlucky for Yelchin that Gibson’s antics loom large, because the Star Trek/Terminator Salvation star is a knockout as the suffering prodigal son, running a lucrative high-school business writing papers for classmates and obsessed he’ll inherit his father’s crazy mantle until a blossoming romance with Norah (Lawrence) begins to shows him another path.

Their relationship is full of sweet melancholy, and to Foster’s credit, she makes every attempt to give the troubled teen strand breathing space alongside the main spectacle of Mr Crazy and his East End marionette.

As a director, Foster’s hallmark is restraint. In an age of anything-is-possible computer-aided razzle-dazzle, you have to admire her insistence on simply wanting to tell a story, no grandstanding, no fuss.

Killen’s original conception was strong black comedy (Jay Roach was going to direct Steve Carell, a hint at the guffaw-assault originally in mind), but Foster has opted to bypass laughter in favour of mining deeper truths.

It’s debatable whether she was right to suck out quite so much comic juice. True, her disciplined, deadly serious approach packs dramatic muscle and justifies the shocking moment that ends all flippancy and sends The Beaver chundering towards its denouement. But there’s no doubt the film could have done with letting its hair down a bit.

At times, it’s rather too much like its lead character, buckling under the strain of invisible constraints, silently screaming to be set free.

Foster care

Equally, while Foster’s spousal bedrock is by default the film’s least interesting character, the actress tones Meredith down too much, a passive wallflower in danger of vanishing into the film’s tasteful, natural colour decor. And there’s something a little bit discomfiting about watching Mel and Jodie get their freak on in an overegged eagerness to show how the Beaver has roused the couple’s sex life from the dead.

However, overall, Foster’s film is stocked with unique, warm-hearted virtues. But it’s still a hard sell, a triumphof- the-spirit tale that’s going to require a triumph of audience will to succeed (for one thing, the title’s fnar-fnar connotations could lead to red-faced explanations at the multiplex: “No, it really is a comedy about depression”).

For Foster’s sake, we hope that the enormous goodwill she’s earned in her career wins out over antipathy towards Gibson. And that between now and opening day he doesn’t end up talking out of his you-know-what again...

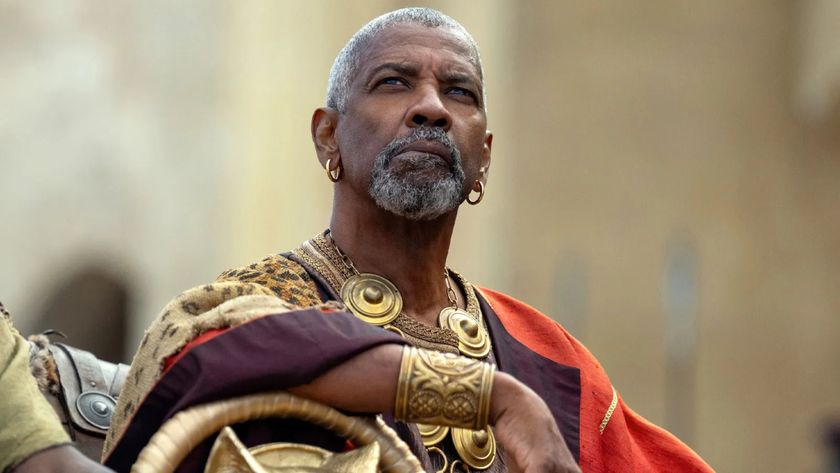

Ryan Coogler promises "I’ve got every intention of working" with Denzel Washington on Black Panther 3

Ahead of GTA 6, Take-Two CEO says he’s “not worried about AI creating hits” because it’s built on recycled data: “Big hits […] need to be created out of thin air”

Getting Over It creator Bennett Foddy threatens the world once again: If you want Baby Steps to be a brutal rage game, "you can inflict that on yourself"