SFX Issue 42

None

September 1998

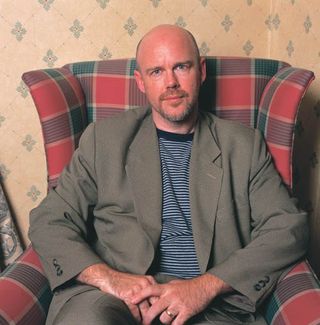

Profile:

Tad Williams

Limb-breaking fantasies may be an easy target, but author Tad Williams reckons they’re a necessary evil. “Not everybody’s into the kind of detail I like,” he tells Anthony Brown.

“When you’ve got to read my books to a deadline, I can imagine their length gets rather irritating,” comments Tad Williams. Multi-volume fantasy sagas which could easily break your foot are hardly rare, but Williams’ Otherland is still unusual. As he admits in the foreword to Volume Two: River Of Blue Fire , he’s writing one 3,000-page novel, and sees little point in giving each instalment an individual ending. “There are practical benefits to writing without artificial closure at the end of each book, with one big arc, instead of a series of little arcs, like molehills.

“I’m trying to get the length which feels right for the story, but it’s not to everybody’s taste. Not everybody’s interested in the level of detail I like. The fantasy audience almost expects things to be in multiple volumes, whereas some of the science fiction readership have been a bit startled.”

Those who lack Williams’ stamina can always jump in at the start of Volume Two , where a ten-page synopsis describes the Webbed-up world of the 21st century, and the Virtual Reality adventures which have drawn a motley band of adventurers into a hyper-VR fantasy world.

“If you look at it as the exposition of the story, then you can just read the synopsis at the start of Volume Two , but then you might as well wait for the final volume. One of the reasons I like big lengths is that it’s like a symphony. Things arrive out of the complexity of it and sink back down, and you don’t have to point them out.”

Given that Otherland is a single novel in four volumes, Williams faced unusual problems writing it – he had to get the plot right first time round, as the early chapters would be in print long before the final volume was even written. “On a single-volume novel someone can go through the whole thing in first draft, think, ‘Damn, I should never have killed off so-and-so...’ and change it. I’ve already published the beginning, so short of going door to door with a red pen and asking people if they’ll let me change their copies to ‘Not quite dead’ there’s not much I can do. So I had to know how it would end. That said, I didn’t get too detailed. I know the vital things, but if I knew everything it’d be four years of stenography.”

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

It also takes effort to keep things under control. “I’d be a lot more worried if I hadn’t done it before, with my fantasy saga Memory, Sorrow And Thorn . By the end of the second volume of that I’d let the sheep stray all over the hills and it took me so long to get the plotlines back together that the last book of the trilogy was as long as the others put together...

“In Otherland , the plotlines are starting towards their eventual finish during the first 100 odd pages of the third volume. The second book was always going to be the most difficult because it has no beginning and no end, whereas I’m going to wrap up some of the plotlines before the end of volume three, and I can start treating it as if I’m in the endgame.”

In which case, why was the second volume necessary to the plot at all? “I wanted to give people an idea of the full breadth of the network, as everybody’s going to get drawn into the same place in the last two volumes. River Of Blue Fire ’s my exploratory volume, where everybody’s expanding out and learning things.”

Indeed, it turns out Philip Jose Farmer’s Riverworld was part of the inspiration for Otherland . “I was listening to an interview with Norman McLean, who wrote A River Runs Through It , and that started me thinking about what a wonderful metaphor rivers were. It had been used in a couple of SF novels, including Riverworld , but I thought, ‘What if the river itself was a metaphor?’ It was pretty quick thinking from there to the notion that if this was a sophisticated VR network then literally anything you wanted could be along the banks of that river, and for a writer like me who’s already one of the most long-winded SOBs you’re ever going to run across, it was as if the doors to the candy shop had been left open!”

The fact that the fantasy worlds exist on computers and have been designed by humans also enables Williams to acknowledge his influences. “I’m a post-modernist writer – you can’t write a near-future book which doesn’t acknowledge that other SF and fantasy stories exist, and have become major cultural myths in some shape or form. You can’t write a book about a young man who’d lived extensively in virtual fantasy gaming environments without acknowledging Tolkien. Tolkien is the rock in the middle of the road so far as epic fantasy is concerned.”

One of Otherland ’s themes is the way people can escape their identity on the Net, so is the fact Robert Williams prefers to be known as Tad significant? “Interestingly enough, I’m one of the least nicknamey people you’ll ever meet – I’ve just always been Tad as long as I remember. I’m even Tad on the Net. But I’ve been on some form of electronic network since 1987, and it’s always fascinated me that so many people have these elaborate personas. You’d suddenly find something out about one of them, and think, ‘My God, so-and-so is a woman?’, because you have prejudices and once the usual indicators are stripped away you start imposing your own meanings on things.”

That’s a point which runs throughout Williams’ work, as shown by the contrast between two characters – the gentle African Bushman !Xabbu, and the psychopathic aboriginal hitman Dread.

“I always want to undercut the obvious, and I used a Bushman to represent some of the ancient wisdom because there’s been a really simplistic anti-First World attitude of ‘white-man-bad, black-man-good’ with other types of aboriginal peoples, whereas the Bushmen got mistreated by both the whites and the blacks. I also didn’t want all the aboriginal characters to be heroes. We all know better than that. We’ve moved past didactic fantasy literature into the real complexities of issues. Nobody has magic powers which are going to save the day, and there aren’t easy answers to anything. It’s a reflection of the way that we all go through life trying to make the best decisions we can, caught up in the grip of things that we don’t have much control of.”

Dave is a TV and film journalist who specializes in the science fiction and fantasy genres. He's written books about film posters and post-apocalypses, alongside writing for SFX Magazine for many years.

The Last of Us HBO showrunner says "flat out" that "I am not going to go past the game" like Game of Thrones did with George R.R. Martin's novels

New Black Mirror season 7 trailer reveals how Will Poulter's Bandersnatch character returns to the Netflix show - with a Sonic the Hedgehog namedrop