Edge Magazine Presents: Game Changers - Sega quits the console business

Sega's Dreamcast pioneered online console gaming, but proved cruelly ahead of its time. Edge magazine investigates a noble failure with fresh insight from one of the men at the top

Presented by Edge magazine, Game Changers is a new editorial series that dives deeper into pivotal moments from console war history, from the original PlayStation launch in 1994, to Xbox’s billion-dollar red ring of death rescue plan. Each episode recaps the industry at the time (The Background), replays key moments as Edge magazine reported them (The Moment), delivers present-day interviews with those involved (The Inside Story) and considers the event's historical impact (What Happened Next?). A new episode of Game Changers will debut at 5pm GMT / 1pm EDT every day this week.

A few weeks ago the venerable Sega celebrated its 60th anniversary. But it could have all been over two decades ago.

Sega’s early expertise was in the emerging Japanese arcade scene, and it eventually became one of the sector’s most bankable hit factories. In the early '80s this heritage would come to underpin the company’s tilt at the home console market, but its first foray was a learning experience: the SG-1000, a decent enough machine, had the bad luck to launch on the exact same day, July 15 1983, as Nintendo’s Famicom.

Thus began the classic back-and-forth between Sega and Nintendo that dominated every playground in the '80s and '90s. But for this story, we skip forward to the most existential moment in Sega’s history: its attempt to survive against the juggernaut that was PlayStation.

The Sega Saturn, after a reasonable start in Japan, had been swept aside. Sega’s last chance was the Dreamcast, a visionary new approach to console design, allied with its own traditional first-party strength. Sega Of America and Sega Japan are at each other's throats.

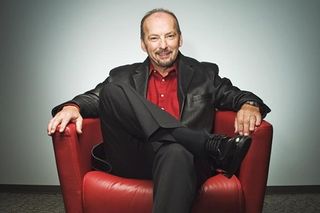

Into this maelstrom steps Peter Moore, who soon after joining Sega Of America becomes the new president of the subsidiary, and responsible for arguably the console’s most important market. This would be do or die.

Edge reported Dreamcast’s launch as it happened. We’ll relive what this last great heave looked like at the time, before catching up with Peter Moore to look back on one of the industry’s most fondly remembered machines – and how Sega, though bloodied and bowed, survived Dreamcast’s demise and saved itself.

The Background: How Sega tried to right the wrongs of their Saturn console and ran headlong into PlayStation 2

Before the Dreamcast, Sega’s 1999 game console, came the Saturn. Dreamcast’s predecessor is important to this story because it was the former console’s failures that informed the design of the latter - and it was that console which pushed Sega over the edge into quitting consumer hardware altogether.

While some of its games remain revered today, the Saturn is ultimately considered a failure of a console. "I thought the Saturn was a mistake as far as hardware was concerned. The games were obviously terrific, but the hardware just wasn't there," said Sega Of America President Bernie Stolar in 2009. Launched in western markets in 1995, directly against the original PlayStation, the Saturn hardware was powered by a dual-CPU approach, with eight separate processing units. Compared to Sony’s machine, it was a programming nightmare when it came to 3D graphics, making it an unpopular option within the development community. Though Sega produced a selection of high-profile Saturn arcade conversions, including the excellent Virtua Fighter, it failed to deliver a Sonic game until late 1996 – and even then it was the mediocre Sonic 3D Blast (AKA Sonic 3D: Flickies' Island). Outside of Japan, Sega discontinued the console in 1998.

Determined not to make the same mistake, and the same financial losses, twice, Dreamcast was designed using more conventional hardware architecture, the more familiar environment ensuring smooth adoption within the development community. Crucially, the console was equipped with a modem, offering millions of players their first experience of online gaming. This was a forward-looking machine a world apart from its predecessor, deserving of a bright future.

Unfortunately, the future had a different plan in store, fuelled by a force that no one within the video-game industry could ignore: PlayStation 2. Rumours and marketing hype centred on the power of Sony’s next console throughout 1999 meant that Sega’s machine seemed obsolete before it had even launched outside of Japan. A target of five million Dreamcast sales by 2001 was set – and missed. The pressure of competitors, plus a change of management at Sega, led to the console’s retirement in 2001, along with Sega’s announcement that it would exit the hardware market and concentrate instead on making games, for delivery across all formats.

The Moment: How did Edge magazine report Sega's exit from the hardware market in 2001?

The news that Sega was quitting the hardware business snagged the cover of Edge 95, dated March 2001. It made the lead news story inside the mag rather than a full feature, suggesting the news broke rather closer to the print deadline than the team was perhaps comfortable with.

“In a brief statement, Sega announces that it is to cease Dreamcast production, but that it is committed to supporting the platform throughout 2001, releasing a list of titles currently in production.” It lacks the drama of the issue’s cover, which zoomed in on Sonic’s face and declared “Dreamcast: Finished. Sega: Unstoppable” (a knowing wink to Edge 60’s “Sega Is Dead, Long Live Dreamcast” cover, back in June 1998).

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Some of the best analysis of the Sega situation came from Edge interviewee Martin de Ronde, of Lost Boys Games. “No need to mourn the industry's loss of Sega,” he said. “Since the consequence of all this is that economic inefficiencies are killed and we are left with the best parts of Sega (its many software divisions), which clearly cannot be held responsible for Dreamcast's poor performance.

"Sony, Nintendo, and quite possibly Microsoft will now see their software line-up being strengthened by top-quality Sega franchises"

Martin De Ronde, 2001

Some of the best game developers in the world can now target an installed user base which is going to be four or five times the size of their previous audience, which basically means it's a win-win situation for almost everyone involved. Sony, Nintendo, and quite possibly Microsoft will now see their software line-up being strengthened by top-quality Sega franchises – and hopefully maracas.” While Samba De Amigo did see a Wii port in 2008, the plastic musical instrument genre, just like the Dreamcast, is now sadly behind us.

The very next issue (Edge 96, April 2001) slapped Crazy Taxi 2 on the cover and declared “Dreamcast rides again”. You have to feel sorry for the game’s producer, Kenji Kanno: his latest game is 60% finished, and Sega announces that it’s quitting the hardware business. No wonder he was in a sombre mood, telling Edge he didn’t understand the success of the first game in the series – the third best-selling Dreamcast game in the US. “I’m very happy, of course,” he said, “but I sometimes get the feeling that it isn’t true, and that maybe it’s only the result of too much hype”. While the first game was an arcade conversion, the sequel was built for a console audience, scoring a solid 8/10 three issues later. It’s telling, though, that outside of Crazy Taxi, there’s only one Dreamcast game in the entire issue, a preview of Headhunter.

Sega’s presence is restricted to the arcade and also its upcoming assault on PlayStation 2. Edge speculated that fear of Sega might push developers toward Xbox, though we’re not sure where Shenmue II’s appearance on both Microsoft’s console and Dreamcast quite leaves that theory. While most Dreamcast game releases had dried up by mid-2001 – the final North American and European release being Virtua Tennis 2 in November that year – they continued in Japan until 2007 with Milestone’s scrolling shooter Karous signing off a console that may have had a short life, but lived long in the memory.

The Inside Story: Peter Moore, President of Sega Of America during the Dreamcast launch

“Our content was still very much Japanese. You know, everything involved samurai swords or ninjas or fish or fantasy. Yeah, well, we certainly saw it coming.”

Peter Moore

Peter Moore, President of Sega Of America during the Dreamcast launch:

“I didn’t know a lot about videogames other than that I’d bought my son a Saturn and that seemed like the worst $500 I’d ever spent, because it was pretty clear to me that shortly thereafter that they’d stopped supporting the platform.

“I spent a lot of time talking to Bernie Stolar, who was the president of Sega Of America, first of all absorbing what the industry was about, and secondly what we needed to conquer at Sega as regards the legacy of the Saturn at that time, and then thirdly how we were gonna get ready for what had been determined to be the launch of the Sega Dreamcast: 9/9/99. And it wasn’t too long unfortunately before Bernie left the company, so within five months I’m the president of Sega Of America.

“From the Sega POV, the more I dove into the brand I understood how it had differentiated itself from Nintendo in the mid- and early-90s: kind of irreverent, the anti-Nintendo, if you will, and trying to take gaming a little bit more to an older audience, away from the fun element to a little bit of an edge. And our marketing needed to reflect that – we needed to differentiate ourselves.

“The irreverence – the kinda Sega ‘bark’ that was well known – had kinda been left by the wayside for a few years, so we brought that back. We knew we had a jump of about six months on PlayStation 2, and went after it so that we could (a) leverage that time advantage we had, and (b) try to get some kind of an installed base that would give us a real good platform for success going forward.

“PlayStation did a brilliant job of FUD-ing Sega and Dreamcast: Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt.”

Peter Moore

“I certainly think we launched it brilliantly in the US – we knew we’d got off to the start we needed to. We’d sold every unit – we didn’t have many units, which is typical of a hardware launch – but we sold every one, and in fact retailers were clamouring for more and were not happy when they didn’t get their hardware.

“We did $99m [in revenues] in those 24 hours and declared ourselves as the biggest entertainment retail launch in history, which it was at the time [laughs]. And the hardware was incredibly well received. I would still argue it had the best content line-up in history with regards to new IP – I thought it was an incredible line-up, and so did the players. They still do. And we were already sold out of hardware, so we were basically air-freighting the console in [to get them quicker], which meant it wasn’t cheap, and that didn’t help with making money on the hardware.

“In retrospect you can probably say [third-party developers] were a little reticent to throw multi-year development investment into the Dreamcast. It had been successfully positioned, I think, from my friends at Sony as a transitional platform, and what both SCEA and SCEE were able to do was say, ‘Yeah, you might buy a Dreamcast, but the moment the PS2 comes out you know you’re gonna move to that’. PlayStation did a brilliant job of FUD-ing Sega and Dreamcast: Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt. The gamer loved it and still loves his or her Dreamcast, but the positioning of the PS2 – things like the Emotion Engine – they did what Sony do really well: they drove hard, and they’ve done that with just about every iteration of PlayStation since.

“They managed to place that sense of uncertainty in the eyes of the gamer. We’d already had a tough time in Japan, and Europe was really starting to teeter a little bit, but [in North America] we felt we could be the salvation, and for a period of time we were!

GamesRadar takes a deeper look at the 25 best Dreamcast games including Space Channel 5, Crazy Taxi and Soulcalibur, many of which went to establish themselves as key series on rival consoles.

“As we were heading into the Christmas 2000 period, which proved to be pivotal, we were flying from San Fran to Tokyo every other week, and it was brutal. We had numbers and targets that we needed to sell to come out of Christmas feeling that, OK, we can continue to drive this business forward.

“[The console business] is a loss-making business in the early years but if you can see light at the end of the tunnel – that your installed base is growing – you can see a one-, two-, three-year roadmap for content coming in, from both first-party and third-party. You could also see with Dreamcast we were trying to maybe change the face of gaming, if you will, to make it more online, more collaborative, more co-operative – getting boys out of their bedrooms, making this thing feel like it was a true entertainment medium rather than something that your 13-year-old son plays sat on the edge of his bed on a crappy TV. And to really mainstream it, that was our goal: to mainstream gaming.

“It’s 20 years ago now that [former Sega marketing chief] Charlie [Bellfield] and I went over [to Sega Of Japan], which was when I kinda knew it was all over, and had what I decided was a manifesto, which was to look at different levels of content and different types of content. [The concerns were] becoming glaringly obvious when you looked at the Japanese style of development at the time, which was: ‘Let the developers figure out what they want to make – then they will let you, the subsidiaries, know’. Maybe at prototype stage, but sometimes even when the game was going into alpha, only then would you figure out what your dev teams were doing. Sega had nine development teams working on projects in this way, and in the modern world this doesn’t happen.

“One of the things that Sega had done successfully was open up through online gaming a broader demographic, a more mature demographic, and it was very clear to me as graphical fidelity was improving that you were able to now create more movie-like content. And so when the GTA phenomenon started to kick in it was clear, despite the initial controversy, that this was the way the industry was going. But our content [at Sega] was still very much Japanese. You know, everything involved samurai swords or ninjas or fish or fantasy. Yeah, well, we certainly saw it coming.

“[Had Sega continued] I mean, they just would have lost more money. The momentum that the PlayStation 2 had developed by March of 2000 and onwards was gargantuan. Developers [at Sega] were saying, ‘We've got to keep going, we've got to keep going’, but you need to understand that at that point, you’re just simply not making any money. And the more you sell, bluntly, the more money you lose. You don't hit an installed base that gives you an attach rate that creates this kind of virtuous cycle. It just wasn't happening.

“And so... yeah, it was Sega Japan that pulled the plug. There's this consistent 20-year-old myth that I killed the Dreamcast. That just never happened – we were an American subsidiary. But everyone knows your face! There's nobody more than me that wishes we could have hit our numbers in that Christmas period of 2000 and rolled right out of there with the wind at our backs. But we couldn't, and we didn't.”

“There were a number of small but cumulative factors that demonstrated that not only was the machine and the games great for their time, [but] they were satisfying the gaming demands of a lot of players. Just that alone was very exciting to see: people loved playing with the product. What we also saw was the way that our marketing came together and really lifted the entire industry from being predominantly a toy category, typically enjoyed by the stereotypical 12-year-old gamer in their spare bedroom. It moved gaming from the spare room to the living room.

“The one thing PlayStation will always be credited with, correctly, is the levelling up of the entire industry from a demographic point of view, and moving it from being a toy business to a full-on entertainment category. And I credit that not just to the machine and the content, but also the way we told the story to the world. That was what kick-started a new generation.”

What happened next?

Just over a year-and-a-half after Sega had blazed back into the console wars, setting sales records and beginning the roll-out of one of the most brilliant first-party software line-ups in console history, the dream was over. In late January 2001, Sega Of Japan made the decision, announcing that it would halt production of its final console, the units rolling off the production line in March to be the last.

Dreamcast would yet see a handful of major software releases, such as Yuji Naka’s stunning Phantasy Star Online and Yu Suzuki’s Shenmue II. Appropriately enough, there was also the Japan-only Segagaga, a surreal love-letter to the company’s history that also served as a middle finger to Sony (and which executives decided not to promote too heavily).

At this point, one of the most important figures in Sega’s history makes a decision. Isao Okawa had been chairman of Sega since 1984, when his company CSK Holdings backed a takeover of the company (alongside co-founder David Rosen). In March 2000 Okawa had become Sega’s president. Okawa made his fortune in IT but adored Sega: he almost single-handedly bankrolled the Dreamcast’s development, then saw how things were going.

Okawa had the foresight to ally Sega with Microsoft for the difficult years to come, to the extent of holding talks about an acquisition with Bill Gates. In early 2001, as Sega finally withdraws from hardware and prepares for the heave of transition, Okawa is in ill health. At this time he forgives over $500 million in debt Sega owes him, as well as transferring to Sega Corporation his $695 million holdings in Sega and CSK.

There is another timeline where the end of Dreamcast is also the end of Sega. Okawa died on March 16, 2001, and his final gift to the company he loved – and all of its fans – was one last, last chance.

Xbox never acquired Sega, but there was the swift announcement of 11 Sega games for Microsoft’s then-to-be-released console (Dreamcast never officially competed directly with either Xbox or GameCube). Over these early years as a third-party publisher Sega made the most of what it had, with in-development Dreamcast titles such as Jet Set Radio Future moving to other platforms while older Dreamcast games were ported to other platforms, finding enthusiastically grateful audiences.

That may have been relatively easy money but Sega has also been doing the hard work, looking at brilliant games that hadn’t worked commercially and somehow converting them into equally brilliant games that did. Shenmue never came close to recouping its development costs, whereas the Yakuza series became hugely popular and is now one of the company’s biggest franchises. It broadened out into strategy games, acquiring Creative Assembly in 2005 and Sports Interactive in 2006, and more recently adding Atlus and Relic.

This past decade has shown a company more comfortable with its history. Perhaps in the early 2000s it felt too raw to fully exploit Sega nostalgia beyond the odd compilation disc, but now there’s everything from the Mega Drive Mini to Streets Of Rage 4. It’s a sidenote but worth noting that Sonic Mania, one of the best Sonic games in 20 years, began as a fan project before receiving the official imprimatur, and acknowledging the internal culture required for that to happen.

Twenty years ago, Sega was a competitor to Nintendo and Sony in the console race. Now it’s a well-established third-party developer that consistently delivers great games across all platforms.

Sega built a brand to sell consoles and, in some respects, that attitude lives on. You see it most obviously in Yakuza, the series it still seems to allow to go anywhere. Being aggressive and irreverent while also playing nice with the industry at large, however, is impossible.

Sega is now a third-party giant, it makes great games, and that was the exit strategy: it worked. But there’s no question of whether, these days, Sega does what others don’t.

Edge Presents Game Changers returns tomorrow at 5pm GMT / 1pm EDT and you can subscribe to Edge Magazine for only $2.77 an issue

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.

Most Popular