The man behind The Walking Dead series and indie hit Firewatch reveals the secret art of telling tales

This interview was conducted by Xbox: The Official Magazine

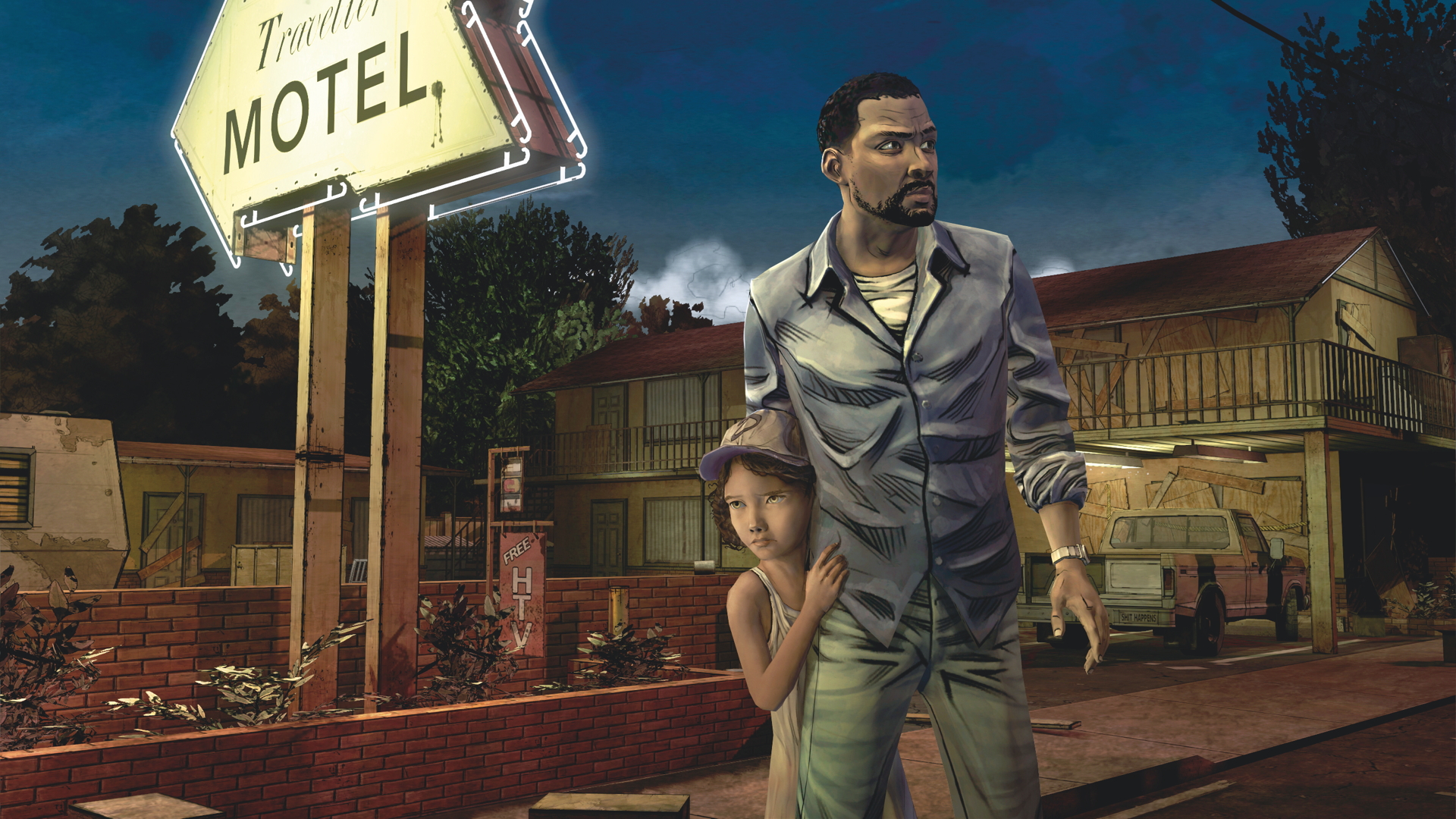

Sean Vanaman was planning a career in television before he joined Telltale Games as a writer and designer. TV’s loss is gaming’s gain, as Vanaman has quickly become one of the industry’s most respected scribes. His work as project lead on The Walking Dead helped earn Telltale a raft of awards, and gripping first-person adventure Firewatch looks likely to do the same for his new venture, Campo Santo. The day after inking a deal with Good Universe for a Firewatch movie, Vanaman talked to OXM about the challenges of interactive storytelling, and why his next game won’t include any trees.

OXM: How did you get started in games?

Sean Vanaman: I was a college student in LA, and didn’t really know what I wanted to study, so I spent time in many different programmes. Along the way, I started working with Disney in their games group just to earn the money I needed to get through college, and I ended up with a degree in Film and English. Around that time, I was writing a lot – I just wanted to make stuff, that’s all I’ve ever really wanted to do. Working at Disney wasn’t the best environment for [that] just because the company was so big and it was hard to get anything greenlit there, especially when you’re a young guy. I was honestly kind of done with games, and I figured with my degree and the friends I had I could probably become a writer’s assistant in TV. But then I met a guy who was an executive producer at Telltale Games and he was looking for more writing-focused designers, and I had experience, and I got hired to work on the Wallace and Gromit series for Xbox 360.

OXM: The Walking Dead marked a turning point for Telltale, and a shift away from the usual puzzle-focused adventures. Did the structure of the company change at all?

SV: In terms of how we made creative decisions and how we solved problems, it was kind of the same: a group of people trying to break the story, trying to figure out what the player was doing [and] arguing over what was good and bad. For the first three years I was there, we didn’t have any concept of writer versus designer, so if you were a designer you were also writing your episode. The one thing that did change was that as the format of Telltale games codified, we started hiring more people who were [purely] writers, and the game designers would build the metastructure for each experience. In terms of the writers’ room and the way we put together an episode or a season, none of that stuff really ever changed. You’d just put everybody in a room and say, “Right, let the best ideas win”.

OXM: The Walking Dead is based on the comic books, but the TV show was taking off as you worked on it. Did that make much difference to how you approached it?

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

SV: When we pitched the game, meeting one, day one, [Robert] Kirkman just sat down and said, “Let’s do something, pitch me some stuff.” Chuck [Jordan], Jake [Rodkin], Gary Whitta and I had concocted the bare bones of the story and came up with Lee and Clementine. We had some Thai food and talked to Robert about it and he was really into it. I think we were all really lucky because The Walking Dead TV show was just exploding and that bolstered the game in terms of public perception. That gave Robert and the guys at Skybound [Entertainment] lots to do, but I never watched the show, because we had licensed the comics and the last thing I wanted was to be passively influenced by what was happening in the show, even in terms of tone. I’ve seen it [since], but when we were working on the game I never watched it.

OXM: Were you prepared for how popular the game would be? And did that change how you developed the story?

SV: You’re always surprised by that level of reception. It was really weird. What [the positive response] did for me personally was give me confidence. That was the biggest thing. I mean, we had a really solid team, we had a lot of freedom and support, but even then you’ve no idea if what you’re working on is going to be successful. You never have any idea how people are going to receive it. I mean, we did playtests and then focus tests and with the playtests I couldn’t really tell if people were into it, and then the focus tests came back and people were super into it. But it was such a small sample size and the game was three days away from coming out. I remember thinking it was a quality piece of work, but if you’re anticipating anything being as successful as that game was, you are delusional!

OXM: The relationship between Lee and Clem is right at the heart of The Walking Dead. What did you draw upon when writing that?

SV: At that time I was thinking a lot about having kids and what that meant, and things like my relationship with my sister... I’ve always been in a role in my life [where I’ve had] to take care of people around me, generally, that’s something that just seems to happen. So I drew on all those things and also thought, ‘Okay, if an eight-year-old girl showed up on my doorstep, what would that be like for me?’ And then what would it be like plot-wise? What’s the sort of s**t that I wish I could say to her, and what would I probably be incapable of saying to her? With Lee, I just knew who this character was so fully and what his capabilities would be in those situations, and then I started writing.

OXM: Was Lee’s death at the end of the season always part of the plan?

SV: Yeah, yeah, that was planned from the start.

OXM: Were you happy to let go of The Walking Dead at that stage and pursue other ideas?

SV: Oh my God, yeah. 100 per cent. I was so happy with the way everyone came together on the final episode. And some of the work that was done? I thought, ‘Okay, I’m good here’. I felt pretty satisfied creatively. When I was thinking about working on more Walking Dead, I was struggling to concoct an ambition, at least for myself. But I was also thinking about the team and what I could personally [contribute]: ‘What am I going to bring to this that’s new and different?’ In the spirit of comics – not so much for The Walking Dead, because Robert writes everything – it’s interesting when other people are involved. Like, what is [Harlan] Ellison’s take on this character? What is [Grant] Morrison’s take? I’m kind of lucky that I didn’t stay around to try because I maybe would have taken an absurd risk.

OXM: Some would say leaving Telltale was an absurd risk...

SV: Well, I’d known since I was basically in my early 20s the sort of place I wanted to come work. And the only way to work at a studio like the one I imagined in my head was to try to create it with some good people. That idea had been in there for so long, and by the time [The Walking Dead] came out, Jake and I felt we were at a point in our careers where we were going to try to do it on our own. [Otherwise] we were going to miss our window to recruit the team that we wanted to work with. People had started reaching out: “Hey, do you guys want to work with these people?” or, “Hey, so-and-so is looking for a development team, we really love The Walking Dead.” By virtue of listening to those calls, it firmly implanted the idea that we could do it on our own. We talked about a lot of possible partners and a lot of possible projects, but Firewatch was the one we kept coming back to wanting to work on. And so we did.

OXM: When did Firewatch start to take shape?

SV: Probably not until the summer after we’d left [Telltale], and it was so character- and world- and story-focused at the beginning, that it took us a while to figure out what the hell you do. We knew we wanted it to be first-person, and we knew we didn’t want it to be like Gone Home – I mean, I love Gone Home and Steve [Gaynor]’s a friend, so I’m saying that with reverence. But we knew we wanted to have it be more active, more like you were playing a main character in a movie or something. As opposed to telling a story of what happened here, this is a story of what is happening now. From very early [on] that was a big ambition of ours.

OXM: Did the success of games like Gone Home and Dear Esther give you confidence that it would find an audience?

SV: That was definitely our understanding. And we felt like we could talk about it and market it like a mainstream game rather than an indie game. It wasn’t a punk-rock situation. We felt like we could do it on a bigger scale if we took some of our creative sensibilities and built on the audience that was being created by the likes of Steve and Davy Wreden [the creator of The Stanley Parable] and folks like that.

OXM: For a game where you spend a lot of your time in conversation, and when the main characters are not physically shown or in proximity to one another, the casting of Henry and Delilah, must have been particularly crucial.

SV: Yeah. It took us so long to find Rich [Sommer]. We auditioned so many people and eventually we reached out to him, because he followed one of our designers on Twitter, so I said, “DM him, he likes games, maybe he’d want to read for it.” His first read was so nuanced and so alive, that we said “Yep! You’re the guy.” Whereas with Cissy [Jones], I called her on the day we started making the game and said, “Hey, I’m writing something I think you’d be great at, and I loved working with you on The Walking Dead, let’s do this again.” It was also about wanting to have one known quantity on the game, having already experienced one piece of the puzzle.

OXM: Is it true they recorded their lines apart to mirror the physical distance in the relationship between Henry and Delilah in the game?

SV: Yeah, that was fully directional. If we had been doing a scene where they were a husband and wife sent out to do this job, then I would have just recorded them in the same space so they could play off each other. But yeah, they didn’t know each other and Henry and Delilah didn’t know each other and I wanted them to get to know each other over the course of the story, so [I said], “Don’t meet. Record in private. We’ll record all the same time and you’ll hear each other’s voices in your headphones, but that’s it.” It did such a decent job of recreating the dynamic between the characters in the game that I think it totally worked. There are times when they’re silent with each other, or times where they’re struggling to feel each other out in their tone, that you just wouldn’t get if they were in the same spot, or if I had forced them to develop a pre-existing relationship.

OXM: What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer or designer?

SV: From Firewatch, it’s not to make a game with a bunch of trees in it! Because computers hate them. We learned a lot of best practices working on Firewatch. We stumbled so, so much and we made so many blunders. For our next project, I’m excited to make new blunders. [As a writer], I never want people while they’re playing to notice the writing. If later on people think, ‘Oh man, I loved the writing’, that’s fine, no problem. But if you’re playing it and you notice the writing, that’s not at all what we want. There’s also an economy of words. If I’m playing a game and I’m running and I hit the jump button, I want to jump then and there, and I want it to feel good. And the same goes with dialogue. If I’m experiencing something and the character is about to say, “So what do you think about that?” I want to be able to select that [response] and boom – I’m into the next moment. My job is to entertain people as much as I can while communicating the truth about the story we’re telling. Just as good level design doesn’t draw attention to itself, I feel very much the same way about writing.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Chris is Edge's deputy editor, having previously spent a decade as a freelance critic. With more than 15 years' experience in print and online journalism, he has contributed features, interviews, reviews and more to the likes of PC Gamer, GamesRadar and The Guardian. He is Total Film’s resident game critic, and has a keen interest in cinema. Three (relatively) recent favourites: Hyper Light Drifter, Tetris Effect, Return Of The Obra Dinn.