The Sandman ended 25 years ago - and is more relevant than ever

Looking back at Sandman and how much it mattered (and matters) to comics

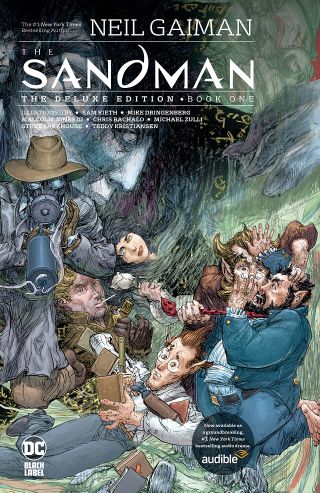

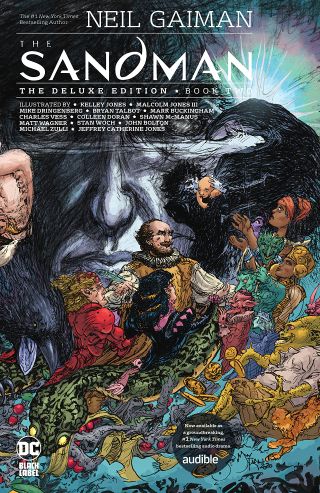

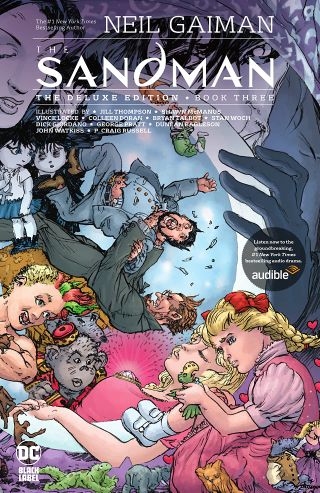

Over the course of 7 years and 75 issues, writer Neil Gaiman partnered with a host of artists and a fledgling DC comic book imprint to create one of the most popular comic book series of all time: The Sandman. The Sandman proved to be a seminal work for the then-newly growing graphic novel format as well as the growing modern alternative comics movement.

Described by none other than Norman Mailer as "a comic book for intellectuals," The Sandman carved a path for not only Gaiman, but also for the Vertigo imprint - DC's first major foray into mature/adult-oriented storytelling.

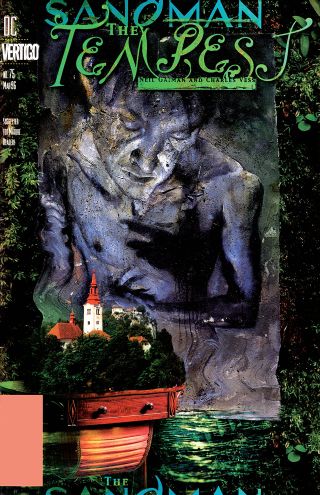

This year marks the 25th anniversary of The Sandman's 1996 finale. Since then, DC has collected these 75 issues in numerous formats, published sequels and spin-offs, and is in the middle of both an audio adaptation and a live-action version with Netflix.

But did the people working on The Sandman back during its original run know to what heights The Sandman would eventually achieve? Vertigo founder Karen Berger, who was the commissioning editor on The Sandman and executive editor on the imprint at the time, said that the series' original pitch from Gaiman and the first few issues were actually underwhelming, relatively.

"I thought it had a lot of potential and there are some brilliant ideas there," Berger told Newsarama in 2011, "but I will admit it took me a few issues into the book to really sort of get a real sense of how great the series is going to be. So, in other words, I didn't know in reading the pitch that this book was going to wind up being such a groundbreaking series."

Gaiman's initial proposal for Sandman proved to be far different from what it would eventually come. Initially conceived as a revamp of the '70s DC superhero the Sandman (created by Captain America creators Joe Simon and Jack Kirby), Berger came back with the request for an all-new Sandman. "Keep the name. The rest is up to you," she was quoted saying in the backmatter to The Sandman #4.

With that in mind, Gaiman wrote an eight-issue outline which was approved, and Berger set up the creative team of Sam Keith (penciller), Mike Dringenberg (inker), Todd Klein (letterer), and Robbie Busch (colorist). Artist Dave McKean, whom Gaiman worked with previously on Black Orchid, was tapped as the cover artist. The early issues, although described as "awkward" by Gaiman, showed a clear trajectory away from the DC Comics superheroes it was originally conceived to be a part of, and into a bold new world.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"When we bought the series from him, I thought he was establishing a real intriguing cast and creating a whole world that hadn't been explored in such a way in comics before," said Berger. " It's interesting that Neil had grounded the first seven issues of Sandman in DC continuity on some level – with some DC characters in there – except for the diner issue #6, which only had the spirit of Dr. Destiny making everybody crazy. All the other issues had an element of other series, which was in some ways a turn-off."

It wasn't until The Sandman #8, the tail end of Neil Gaiman's original proposed story, that the series begin to find its own footing, according to Berger.

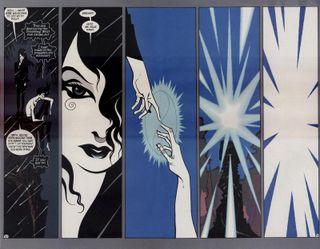

"I preferred when the series found his own voice, he broke away from any connections to those previously established. With the introduction of Death in Sandman #8, Neil really found his voice as a writer. I really thought the tone of the series was really established and got a sense of the possibilities."

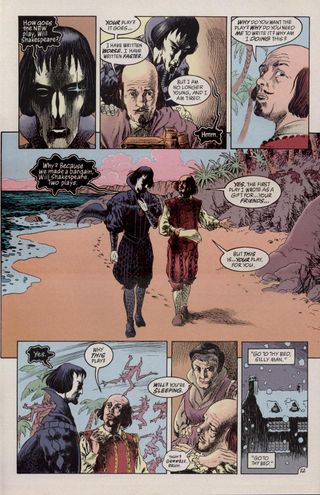

The series followed the character of Morpheus, the lord of dreams. Inspired not by the comic book Sandman but the mythical character from Western folklore, the initial stories about Morpheus show him escaping from 70 years of captivity. After the requisite revenge is accomplished, he sets about rebuilding his home realm, the Dreaming. After 70 years alone, he is shown to be summarily harsher to his recently reunited friends. Although the series initially delved into darker horror elements, it expanded quickly to encompass fantasy and mythological elements. The series proved to be a story of Morpheus himself, but also a framing to tell various other stories with other characters in Morpheus' realm of influence.

After original series penciller Sam Keith quit the series after just three issues, inker Mike Dringenberg took over for a time. The Sandman later turned into a showcase of various artists both new and established from comics, including Chris Bachalo, Kelly Jones, Colleen Doran, Bryan Talbot, Mike Allred, Jill Thompson, Michael Zulli, Charles Vess, and more.

In the following seven years, The Sandman's stories of the dream king and his dysfunctional family saw itself recognized numerous times, with eighteen Eisner Awards, a World Fantasy Award, and considerable mainstream attention. Anecdotal evidence suggested that the series audience skewed away from traditional comic book readers, leaning towards more female readers and those wanting more mature comics than traditionally published. It helped define an audience for the author, the title, and for DC's mature reader comics line itself.

"I first became aware of [the atypical audience] from Neil," said Berger. "Neil did a lot of signing tours, and he and I both observed a noticeable shift in the crowds attracted to this comic. Yes, a lot of young women with dark hair, but also a lot of men and even some traditional superhero comics readers. We'd talk to them at public events, but also by mail and via retailers.

"Creatively, Sandman started reaching out to people who normally didn't read comics," she continued. "Women were reading, and people that normally wouldn't walk into a comic bookstore would come in to buy an issue and walk out. And so we really felt we were attracting different readers, and the collections were a response to that to get it further out to people who didn't necessarily come into comic book stores every month."

While not the first graphic novel from DC, the initial collected editions of Sandman proved to be a sales juggernaut for the publisher – both in comic book stores and the then-new world of traditional book stores. Although the title gained initial popularity with its single issues in comic book stores, the collected editions in book stores showed a brand new side of comics to those who didn't necessarily read comic books regularly.

Over the course of 75 issues and several spin-offs, Gaiman created a family for the Sandman, as well as a supporting cast that has gone on to star in their own individual books. The series helped propel not only the creators but the line itself. Initially created as a DC title, it was Sandman and other associated titles under Berger's purview that led DC to formally establish Vertigo in 1993. Vertigo went to encompass the informal titles that led up to it with new titles such as Preacher, The Invisibles, 100 Bullets, and others to become a pillar of the growing comics medium.

But when Gaiman announced he was ending the series with Sandman #75 in 1996, the comics-reading public was shocked; at the time, the series was outselling DC's own Superman, and the title had become the flagship of the expanding Vertigo line. But for Gaiman, it had been in the cards for a while.

"Could I do another five issues of Sandman? Well, damn right," Gaiman said in an interview with Nick Hasted for The Independent in 1996," And would I be able to look at myself in the mirror happily? No. It is time to stop because I've reached the end, yes, and I think I'd rather leave while I'm in love."

Although the ongoing series ended in 1996, the true effects of The Sandman were only truly felt after there wasn't a new issue on stands each month. Was its absence making the heart grow fonder? No, more so it was DC's (and the larger comic industry's) gradual normalization of keeping comics in print through collected editions (and now digital versions), pared with the positive word-of-mouth from the readers it accumulated over time - be they critics, creators, or fans.

"Because Neil had established such a unique series, he really changed the playing field in terms of what you can do in comics," said Berger.

Although Gaiman has returned on two major occasions - the 2003 anthology The Sandman: Endless Nights, and 2013's The Sandman: Overture - the end of Sandman as an ongoing and becoming a hallowed favorite that returns only on special occasions made it an early model for keeping the specialness of a series alive.

"Even his decision to end the series; one of the things at DC that we came to realize is that on certain titles, it doesn't make any creative sense to go any further," Berger said. "It works stronger in the long run if you have the guts to creatively complete a story than keep going on and on. All good things come to an end eventually."

Read our deep dive into the first volume of The Sandman.

Chris Arrant covered comic book news for Newsarama from 2003 to 2022 (and as editor/senior editor from 2015 to 2022) and has also written for USA Today, Life, Entertainment Weekly, Publisher's Weekly, Marvel Entertainment, TOKYOPOP, AdHouse Books, Cartoon Brew, Bleeding Cool, Comic Shop News, and CBR. He is the author of the book Modern: Masters Cliff Chiang, co-authored Art of Spider-Man Classic, and contributed to Dark Horse/Bedside Press' anthology Pros and (Comic) Cons. He has acted as a judge for the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards, the Harvey Awards, and the Stan Lee Awards. Chris is a member of the American Library Association's Graphic Novel & Comics Round Table. (He/him)