As a queer person who’s been gaming pretty much all her life, it’s blatantly obvious to me just how scarce the kind of representation I want, perhaps need, is in video games. 179. That’s the number of commercially released games my search found that feature queer characters. It might seem a lot, but in the grand scheme of thousands upon thousands of released games, it’s really not much. It’s even less when you consider how few of those characters are even significant. Of those 179 games, only 83 have queer characters who are playable. And of those, only eight feature a main character who is pre-written as queer as opposed to them being queer as an option. Just eight.

There’s more to representation than numbers but they certainly highlight the issue at hand. Which is to say nothing of how poor or outright offensive some of that representation is.

Back in the ’90s queer characters were scarcely present in any of the mainstream media available, but in video games they were almost nonexistent. The first game to feature the word homosexual was the 1995 text adventure The Orion Conspiracy. Players took on the role of a father searching for his missing son and incidentally in the course of that investigation, they meet their son’s boyfriend and learn about his sexuality.

The first game to actually feature a queer character was 1986’s Moonmist, where one of the randomly selected plotlines featured an artist, Vivian, who was in a relationship with another woman, Dierdre, who was married to a man. Dierdre is deceased by the time of the game, though – heaven forbid two women have an ongoing and happy relationship in fiction.

Perhaps more significant than either was 1998’s Fallout 2. Not only was this classic RPG the first game to include same-sex marriage but it included it at a time when same-sex marriage was still illegal around the world. Civil partnership didn’t even exist in the UK yet.

GTA: Sans-inclusivity

Of course, the vast majority of what queer content existed was, well, awful. You couldn’t grow up around gaming without being exposed to the medium’s biggest series, Grand Theft Auto. Rockstar’s magnum opus was chock-full of homophobia and stereotypical queer characters who were only there to be the butt of jokes. Gaming’s poster child was anything but inclusive.

Transgender characters, especially, were the subject of much derision and stereotyping. The ongoing saga of Nintendo character Birdo’s gender has become a running joke. Final Fight’s developer Capcom felt that players would feel bad beating up a woman, so its bizarre “solution” was to write into the manual that female enemy Poison was transgender, which is wrong on so many levels it really deserves some sort of award. This trend still continues today in a handful of more recent titles – for example, Atlus’ Catherine, which treats the gender identity of the character Erica as an elaborate joke.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But then things began to change. EA and Maxis’ The Sims was an absolute phenomenon that even those who didn’t game regularly or at all found themselves playing, which makes it pretty cool that the debut game shipped with same-sex relationships. In truth it’s an inclusion that only came to be due to an oversight; queer relationships had been removed from the game but were re-added when programmer Patrick J Barrett III was accidentally given an old design document and simply re-implemented them (bless you, Patrick). To their credit the developer and publisher did embrace it after this, to the point where expansion Hot Date was marketed on the basis of its potential queer relationships with an advert where two men hook up at the club. (Look, small steps okay?)

Unjaded Empire

The biggest sea change for queer representation during the decade that followed was Bioware’s lauded RPGs. While it wouldn’t be until 2005’s martial arts epic Jade Empire that queer relationships became an option for the player character, Bioware took its first clear step towards better inclusivity in Knights Of The Old Republic with Juhani, the Star Wars’ universe’s first canonically gay character. Though her sexuality was far from explicit, with a fair number of players unaware that this was even the case, it was the start of something bigger for Bioware.

“When we created Juhani in KOTOR, we were just trying to find an interesting character,” Drew Karpyshyn, writer on KOTOR, Jade Empire, and Mass Effect, explains. “We were just trying to find ways to make the characters unique... But, of course, at the time there weren’t [any] gay characters or bi characters in Star Wars so we had to tread pretty carefully. ”

2007’s Mass Effect wasn’t the first Bioware game to do queer romance but it was here where the game’s sheer popularity and the fondness for the characters generated a significant queer audience – something that led to each subsequent Mass Effect title and Bioware’s fantasy series Dragon Age including more and more options for queer romance.

“I think the big thing is we want to be inclusive to the audience but the reason that we want to do that is because we’re telling interesting stories, we’re telling stories about interesting characters so we’re doing it because we want to tell a good story and I think diversity, inclusion, is just a tool storytellers need to use. It lets you tell stories you couldn’t otherwise tell, to reach audiences you wouldn’t otherwise reach.” Karpyshyn explains.

As Bioware catered to a neglected audience, greater inclusion began to take hold elsewhere. The first Borderlands featured no queer characters, but for the sequel, writer Anthony Burch – known for webseries Hey Ash, Watcha Playing? – was brought on board, and his presence was the start of a push for change.

“The idea was to work on characters that were not the norm of what you’d expect from a triple-A shooter where it’s typically cis het white bros,” Burch says of his work on the game. His efforts took root elsewhere in the studio.“Eventually it got to the point where it wasn’t even my idea to make [Janey] Springs gay in Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel. That was just something Matt Armstrong, one of our lead designers, came up with and it was really cool to see.”

Borderlands’ inclusion of queer characters came under fire – not just from homophobic boglins online, but from members of the queer community who felt that the characters’ sexual identities were too explicit. “[I] don’t really care about that critique because I think it implies that gay people should stay in their lane or it should be a thing you discover slowly rather than allowing someone to express themselves the way they want to. So like I’m bisexual and I tend to be the kind of person who just brings that up early. So the characters I write tend to as well,” says Burch.

While some things have changed for the better over the years, other aspects of queer representation have simply taken a step sideways. Early titles, for example 2001’s Fear Effect prequel Retro Helix, marketed their lesbian couples as titillation, making them eye candy for the games’ perceived audience of young teenage boys rather than valid, rounded characters. We don’t really see that any more (thank goodness), but nowadays we do see publishers queer-baiting, which is to say touting inclusion in an attempt to gain kudos and to market a game to a queer audience while completely failing to follow up in the game itself. Tracer may be the poster child for Blizzard’s massive success Overwatch, but the fact she’s a lesbian is left to a small online comic with no mention of her sexuality making it into the game itself. Years of being starved of representation have left the queer community grasping onto the thinnest of subtexts in titles such as Final Fantasy and Tomb Raider, things that seemed to be played up in recent games but again without ever becoming explicit.

Breakout game Gone Home helped change things by not just being inclusive but having a story centred entirely around queerness. In Gone Home, Katie is visiting her family’s new home only to find them absent, and so players must explore the house and discover what has occurred in her years away. Its through this that Katie learns the story of her young sister Sam, who has been coming to terms with her sexuality and falling in love with a girl at her school, Lonnie.

To have a game that focused entirely on a small story about identity with no fantastical elements whatsoever, was quite the revelation. For developer Steve Gaynor, one of the founders of Fullbright Games, the story was the entire point.

“It was Karla [Zimonja] (co-founder of Fullbright Games) and I talking about what kind of game we wanted to make, which was a game where you discover the story just by exploring an environment and there’s no combat and there’s no Myst style puzzles or anything,” Gaynor explains. “It’s just this place. And that gave us the opportunity to make a story that was just about normal people, which there’s not a lot of in games and there wasn’t at that time certainly. So we were like ‘What if the place is just a family’s house? What is the conflict or the drama within that family? What happened there?’ And we arrived at this idea of there being this generational conflict between Sam’s parents and her about who she’s in love with.”

Gaynor’s efforts to make the story as authentic as possible even ended up bringing new faces to the studio “I interviewed Emily Carroll... just because I knew her from my online social circles and I wanted to talk to women who had grown up queer in the ’90s or around that time, so reached out to Emily, that’s how I met [her wife] Kate Craig.” Kate worked on the game as an environment artist, and Emily provided illustrations.

Memory games

While Kate was mainly involved in building Gone Home’s rooms and objects, filling every inch with period authenticity, her own experiences informed the shape of some of the game’s story as well. “I had a lot of friends growing up who, when they came out to their parents, their parents acted not with anger but a sense of... like, they were very patronising or a sense of disbelief, the ‘it’s just a phase’ sort of thing. Part of that made it into the game certainly, it’s in the dining room I believe, the conversation Sam has, but that’s something that I watched friend after friend have that conversation and it always went that way. Because you have nice parents or whatever growing up and a nice home but they’re maybe a little bit conservative so the way they respond isn’t normally in the case of my immediate friends, not anger really, it was just a “you don’t know what you want” sort of thing.”

We’ve now begun to see big studios invest in Queer representation. Dishonored: Death Of The Outsider, Prey, and The Witcher 3 all feature prominent queer characters who are playable. Yet none of those struck a chord quite the way episodic title Life Is Strange did. The game about teen life danced around a subtext of queerness, but its prequel, Before The Storm, gave players an explicit romance between characters Chloe and Rachel. The game was handled by a different studio from the original – Deck9 Games.

“This simply came from trying to be true to the characters that Dontnod had created in Life Is Strange,” game director Chris Floyd explains. “To listen to Chloe talk about Rachel, you know their relationship was intense. To Chloe, during the time after her father died and while Max was gone, Rachel meant everything. It could be a whirlwind platonic relationship, for sure, of the sort we can imagine high school girls striking up. But it could also be a life-altering romance. And that felt entirely true to those characters as we knew them... Allowing players to participate in this kind of love story immediately felt exciting and relevant and, frankly, necessary to us.”

The Last Of Us also made a huge impact for queer representation in the AAA market. While the main game had one of its supporting cast, loner and ruthless survivor Bill, revealed quietly to be a gay man, it was the game’s DLC, Left Behind, where main character Ellie was shown as queer, that resonated with many players. Plenty argued that it was a shame to see this representation relegated to DLC, but for many others, to have such a great and well-known character as Ellie in one of Sony’s biggest titles be a lesbian felt like a momentous moment.

As happy as people were to see them, neither Life Is Strange nor The Last Of Us offer happy endings for its queer characters, however, playing into the unfortunately prevalent trope of Bury Your Gays in which queer characters frequently meet tragic ends.

Pride share

Still the response from fans, those who’ve gone a long time without representation in their favourite games, has been a source of pride for many of these creators.

“It was really encouraging,” Anthony Burch says of the response to his games. “For every dude that hated the fact Torgue says friendzoning isn’t a real thing or reacted against all the social progressive stuff that was in the game there would be somebody who was like, “Hey, I didn’t know I was trans till I played Borderlands,” or “I didn’t know I was asexual till I played as Maya and found somebody to identify with.” Hearing that you’ve allowed somebody to use fiction to learn more about themselves, to feel more empowered, is the only time you can feel like ‘Oh I’m doing a good thing by writing video games.’”

Taking on the characters of Life Is Strange was quite the challenge for Chris Floyd but he couldn’t be happier with the results. “I think we had a sense all along that this would be energising for many fans, who recognised Life Is Strange as a game that tells everyday stories that are often neglected. That’s how we felt, so we were confident others would too. It was very satisfying to see them sharing some of our favourite scenes with Chloe and Rachel and discussing the love these two young women have for each other.”

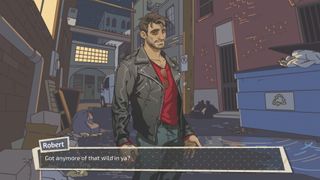

Perhaps the most meaningful representation can be found in smaller indie titles. Games such as Night In The Woods and Dream Daddy depict queerness with a casualness that’s welcoming to those who’ve gone so long without seeing themselves in video games. Steve Gaynor is incredibly excited about this change.

“When I look at games now after a bunch of years have passed and that stuff has continued to expand, and engines and software tools have gotten even more accessible and there’s platforms like Itch.io, and Steam has opened up more, and so on. And I see games such as Butterfly Soup, one of my favourite games of last year, being made by a queer young woman about queer young women as a very direct personal thing. Not something like when I was working, “Well, gotta do a bunch of research.” No, this is the person representing herself through this work and releasing it.”

Queer to stay

Butterfly Soup is a visual novel game about queer young women, available on indie platform Itch.io, by Brianna Lei. It shows their passion for baseball and their day-to-day lives, and feels authentic in a way almost nothing created by non-queer creators does. “There’s just not enough media starring explicitly queer main characters, especially queer Asian American teens. Especially not games,” she says. “I made this game hoping it would resonate with people, so it’s super rewarding reading people’s positive responses and seeing fanwork! While showcasing the game at GDC this year, someone cried when telling me how much they liked the game and I won’t ever forget that. I want all my games to have this kind of impact on people.” Though her measure of success isn’t just about the fans she’s gained.

“Every once in a while, I also see whiny comments from people who haven’t played it, yet hate it. To me, this is a sign that I’ve made it! Whenever I see these I’m filled with energy that helps me keep making games that make narrow-minded people miserable.”

The real victory of this progress is that a whole generation of young queer people are able to grow up seeing people like themselves and discovering their stories, to get a chance to better understand themselves. To see themselves as fully fledged individuals and heroes. The fight is far from over, but the future of queerness in games is looking brighter than ever.

This article originally appeared in GamesMaster Magazine. For more great gaming coverage, you can subscribe to GM here.

Lumiose City is going through an "urban redevelopment plan" in Pokemon Legends Z-A, and I bet it has something to do with the 1100lbs battles on its rooftops

In classic Nintendo fashion, the latest Pokemon Legends Z-A reveal left out the best part: the Lumiose City map looks great after a massive overhaul in the 12 years since X and Y

Most Popular