Playdate: how the publishers of Untitled Goose Game built a console designed to spark pure joy

Created with care, for people who love videogames, Panic’s dinky handheld is the console no-one saw coming

We didn’t see it coming either. As Panic Inc. co-founder Cabel Sasser leads us through the streets of San Francisco, looking for a place to show us his top-secret project, we’re convinced we’re about to see a game. A quiet corner of a coffee shop is apparently not private enough, even though we’re sure we could hide a screen from view. Then again, Sasser’s not carrying a laptop – in fact, he doesn’t appear to be carrying anything at all. Halfway up a nondescript stairwell, it turns out, is the ideal venue to unveil what Panic – maker of Mac and iOS software, publisher of Firewatch and Untitled Goose Game – has been working on for years. Sasser smiles, and reaches into his shirt pocket.

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, you can save up to 54% on a print and digital subscription.

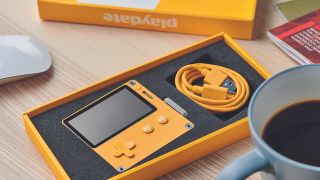

In a flash of sunshine yellow, out comes a tiny handheld console. It’s Game Boy-like, a D-pad and two chunky buttons sitting below a screen. It’s perfectly square, however, and remarkably slim. In the hands, it’s pleasantly weighty. There’s a softness to the matte plastic shell, which we can comfortably grip while clacking the shiny buttons. It feels like it costs money. Little wonder: the industrial design, Sasser tells us, is the work of revered Swedish electronics manufacturer Teenage Engineering.

Were it simply what it first appears to be – a high-class retro homage to the Game & Watch – it would be surprising enough. This is a week during which we’ve just seen Google waltz into the game industry with a grand vision for a cloud-based future in which boxes are a thing of the past. Yet here is a man with a portable console of almost belligerent boxiness.

And the surprises keep coming. For all its retro trappings, this is a thoroughly modern bit of hardware. The 2.7-inch black-and-white screen has a resolution of 400x240 – around four times the pixels of the Game Boy’s screen. Much like the E-ink screen you’d find on a Kindle, it’s not backlit – the difference is that it’s tremendously reflective, the visuals wonderfully sharp and clear in the California sunshine. The in-built speaker looks minuscule, but is so powerful that we have to hurriedly hunt for the volume controls, lest any passers-by be alerted to the existence of this bizarre little gizmo.

Then there’s the contemporary modus operandi that gives the console its name. Every Monday, via WiFi, owners receive a new game, the notification light on top of the case blinking to announce its arrival. Whenever you have five spare minutes, you’ll be able to reach into your own shirt pocket, and make time for your Playdate. And these games aren’t your basic Game & Watch fare. They’re specially crafted titles from such indie superstars as Bennett Foddy, Zach Gage and Katamari Damacy creator Keita Takahashi.

It’s the latter’s game that reveals the last surprise. We boot up Crankin’s Time Travel Adventure, but now none of the buttons seem to be working. And then we notice the strange metal rod on the right-hand side of the console. Sasser gives it a tug. From inside the shell, a diminutive crank pops out. We turn it, and our hero begins to move, in the way only a Keita Takahashi character can move – bouncily, ridiculously, with a lurid array of squeaky sound effects – and we start to laugh. And isn’t that quite the point? This little yellow curveball, for all its absurdity, is purpose-built for happiness.

Growing pains and the route to joy

Some time ago, Sasser had a bit of an existential crisis. “Panic grew so slowly and gradually that one day I woke up, and I realised, ’Oh god, we have 20 employees, and revenue is into two million dollars’,” he says. “I’m responsible for the livelihood of a lot of people. It definitely snuck up on me. And so I crashed pretty hard. Like, ‘can’t really get out of bed’ hard.” Fortunately, his friend and co-founder Steven Frank was on hand to help him through it. “We talked a lot. ‘Why am I feeling this way? What is happening to me? How do I reboot myself? What are we doing? Where are we going?’ And one thing that came out of that conversation was a realisation that we are extremely lucky, and in a very unique position.” Panic is beholden to no-one: it doesn’t have a board of directors, any investors to please or loans to repay. “There’s nobody telling us what we can and cannot do. That is preposterously rare. And I don’t think I realised that.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

“I feel like that’s the true origin story of this device,” Sasser continues. “A part of my brain unlocked, and I realised we don’t have to always keep doing the exact same thing that we’re always doing – this ceaseless development-and- support cycle. We can do some weird things too, as long as we’re not betting the farm. And if we have this chance, we should probably start doing some things that can take us to new places. Maybe they’ll work, and maybe they won’t. But if we’re not doing that, we’re just wasting our lives. Yeah, so um, that’s kind of heavier than maybe you were hoping for,” he laughs, “but it’s true.”

Indeed, Playdate is much more than anyone might initially bargain for. While a niche proposition, it feels vastly of the moment. A standalone portable device that offers a reprieve from the stress of your smartphone; a hand-curated selection of high-quality games; an input method that encourages game developers and players to design and interact in a new way – Playdate’s candy-coloured coating may just be the spoonful of sugar that makes the medicine go down. In an industry accelerating towards homogeneity, this is a left turn, designed to remind us of the value of doing things differently. In that respect, perhaps Playdate is not so surprising after all. This feels like it’s been a long time coming.

Five years, to be exact. Panic had just gone out on a limb, even by Panic’s standards (this is a software company which has dipped its toe into making skins for its virtual MP3 player, and even produced the official T-shirts for Katamari Damacy), having agreed to publish its first game, Firewatch. “To be totally honest, if Firewatch hadn’t been successful, there’s a chance Panic wouldn’t still be here,” Sasser says. “It was a big bet. But it felt so good to do something different.” The bet paid off: Firewatch was a success, selling over 2.5 million copies by 2018. Panic even came up with the idea of allowing players to send off their in-game photos to be ‘developed’ and mailed to them in real life – and, as it turns out, eventually hiding a virtual model of Playdate in the game. It was an exhilarating time. “In the back of my mind, I was like, we have all these talented people. There’s probably nothing we can’t do, within reason,” Sasser says. “I’ve always dreamed of hardware – but when you’re a software company, it’s preposterous to try to pivot into hardware. Like, that’s a ridiculous notion. But it’s something that we had never done. And for whatever reason, I felt confident that we could try.”

The company’s 20th anniversary was coming up, and so this hardware project – early ideas included a commemorative clock – could tie into that. And then Sasser found the Sharp Memory LCD screen: black-and white, high- contrast, harkening back to the original Macintosh, and beautiful. “I have a vague memory of Cabel saying something like, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to make a little thing?’ And sort of describing it as a shape like this,” co-founder Frank says, demonstrating with his hands. “You could tell he was visualising it as an object, and he was saying, ‘It could be a little thing, and have some games on it. Could we do something like that?’”

Sasser’s earliest idea for Playdate was that it’d be a simple Game & Watch-style toy. Immediately, he called on the talents of in-house engineer (and amateur boat-builder) Dave Hayden. “Dave is the kind of guy that you can just throw ridiculous tasks at,” Sasser laughs. “That’s really part of the secret, is going to Dave and saying, ‘Do you think we could make a handheld game system?’ He had basically no electronics experience at that point, but he was like, ‘Sure, I could figure that out.’ And amazingly, did.” In 2015, prototyping began in earnest. Hayden’s weapon of choice was a hot plate, liberated from his own kitchen, on which he melted solder for the circuit board.

Panic continued to work on developing and updating its MacOS software, with Hayden occasionally tinkering away on the team’s strange experiment in the background. At the same time as the first prototype was coming together, Sasser and team began to consider the software side of their 20th-anniversary project. “It was the era of new streaming video services: Netflix was producing shows, and Amazon was starting to do it,” designer Neven Mrgan says. The services were releasing all episodes in a series at once. “It sucked the fun out of it. You just got this bucketful of content, and then it’s gone the next day, and the conversation is over. So that led, I think, to the season idea: what if there was something new every week?”

Prototyping Playdate

Hayden 3D-printed a rudimentary shell for the circuitry, and it could play an LCD game (you delivered files as Panic’s Transmit truck). “But then a week later, it changes to another LCD game,” Sasser says. “And you’re like, wow, there’s multiple games on here!” The problem, however, was that Game & Watch-style fare didn’t stay fun for very long. If they were going to sell these devices to Panic’s supporters, they wanted them to get their money’s worth. “And that was the huge leap mentally to, ‘Well, maybe this thing just plays real games.’”

Gradually, more and more of Panic began to get involved with the project, with Greg Maletic assigned as project lead. “Budget-wise, it was deceptive because we moved so slowly and steadily that it was never a huge strain on resources,” Sasser says. “It’s like, oh, it’s just Dave and Dan [Messing, engineer], and he’s got the hot plate and it’s not costing us a lot.” They would constantly evaluate whether they had enough money to continue their pet project without endangering the livelihoods of their employees. “I mean, it’s probably laughable to professional businesspeople that this is basically the extent of our financial planning: we open up the bank website, see the amount that’s in the checking account, and say, ‘Okay, I guess we can keep going with this’,” he laughs. “That is something, of course, that I did often. And there were definitely junctures, especially when manufacturing showed up, where it’s like, ‘Oh god, this is real money now.”

The end of 2016, he estimates, was the point at which they were “crossing the Rubicon”. It was time to get serious. Hayden could build a board and the team could write code, but they were missing two pieces of the puzzle: mechanical engineering and industrial design. Sasser secured a meeting with the CEO of a local, well-known industrial-design company, bringing Hayden and Mrgan along with him. “We showed up in a conference room, and they had brought in consultants. And so I started to pitch this idea, excitedly and animatedly.” The response was overwhelmingly negative. “The first question from the CEO was, ‘Do you really think anyone’s going to buy this?’ I was like, ‘I’m not sure. But it’s something we really want to do, if you can help?’ And then the consultants were like, ‘It’s going to cost you, bare minimum, a couple million bucks to even remotely get this thing off the ground.’”

Mrgan had anticipated something like this. “Everyone was wearing slacks and dress shirts in the office. I mean, I know that’s such a clichéd way to like separate companies, but that’s the kind of company it was.” They bragged about manufacturing products for casinos, which he found distasteful. “It was very much, unless we were making the next register checkout system that was going to be sold to Safeways across the US, then we were jokers, and we were wasting their time. We were never going to make this, and we should just 3D print it and put it on Kickstarter. Like, ‘Why are you even trying this?’”

Sasser’s reaction quickly turned from terror – perhaps this was a bad idea – to anger. “It was one of the only times in my life that I felt like leaving a meeting. Maybe they were right. But all I could think of was, ‘I know those things that you’re telling me, we know that this is a weird idea and a wild adventure. And although we’re pretty confident it will find an audience, there’s a very good chance it won’t’.” It was a demoralising time, but it also lit a fire under Sasser.

"Yes! You understand me! Those other jerks, they didn’t understand! But you understand!"

Cabel Sasser, Panic Inc.

“I remember returning to the office, sitting and thinking, who makes things that have the spirit of the thing we want to make? You can tell when a product is made by people who care about the thing, rather than by a corporate decision about the marketplace. This is not, ‘Q4: get into handheld gaming’, or whatever – we just want to put this thing into the world. And of all the stuff that I had come across and owned personally, Teenage Engineering was the company that most felt like that to me.”

Sasser has always loved Teenage Engineering’s synthesizers and sequencers, beautifully designed bits of kit in which the makers would often hide videogames. He had no real connection to the company (at least he thought not – he would later realise that he was one of the only people to buy a box of merch for NetbabyWorld, a Shockwave game site that Jesper Kouthoofd, one of Teenage Engineering’s founders, had worked on. The same font on that box is now the Playdate font). But he sent an email anyway, and eventually got on the phone with Kouthoofd. “I gave my extremely excited, rambling speech about this handheld system. There was this long silence, and Jesper’s like, ‘Well, can we make a game for this thing too?’ I was just like, ’Yes! You understand me! Those other jerks, they didn’t understand! But you understand!’”

Crank it up

In fact, Kouthoofd understood what Playdate should be so well that he almost instantly added one of its defining features. “Jesper emailed his very first render concepts of what this thing could look like, and there was a crank on the side that we had never seen before,” Sasser laughs. “That was an incredible inspiration. Like, we don’t have to make this thing be like everything else. Jesper definitely has that vision when it comes to hardware. We’re software guys, and we know we can push the boundaries of software in all sorts of different directions. But I don’t think it would have occurred to me in a million years that we could put this rotating, ridiculous handle on the side that flips out.” Like Sasser, the rest of Panic were instantly sold, Frank recalls: “We were like, ‘It’s so weird’. But that’s exactly right for this device.”

The suitability of Kouthoofd’s idea was a fantastic sign. “He’s like, ‘Oh, and the crank is like a crank control.’ We’re like, ‘Great, sounds good!’” Sasser chirps, then laughs. “It’s one of those things where you just immediately get it. We’re so fortunate to have found people that are on that wavelength. Yeah, of course, a crank! Think of the stuff you could do!” The project was energised yet again: Hayden was off learning about Hall effect sensors for the crank, and Sasser was throwing yet more potential wild cards at him. “I became fixated on this idea that if we were going to give people a season of games, the finale had to be something special,” he says. “And now we intend to do that in software, but for a while I had this notion that there would be a second colour screen hidden inside the device.” The last game in the season would tell players to unscrew the back of the device to uncover the screen; a similar concept of a hidden crank that players could find and plug in was pitched, as was a slider below the buttons and a secret accelerometer. All were abandoned in favour of not biting off more hardware challenges than they could reasonably chew. “Dave was very polite and definitely humoured me on the colour screen, while also in a very Dave-like way making it clear that it was a very bad idea,” Sasser laughs.

It was a giddy, strange time at Panic. iOS showed up, and the company was branching out into apps for iPhone and iPad. It took a lot of work, and the apps were far from successful, which was scary. “And suddenly we were finding ourselves in a weird position of no longer being able to do whatever we wanted, which is why we got into computers in the first place,” he says. “We could have had an idea for an amazing iPhone app, but it’d have been against the rules, or we literally couldn’t build it. And all of these things are happening while we’re building this device, where we have total control and the sky’s the limit, and it’s real software and something physical. To feel both these things happening at the same time... it’s very hard to keep that balance. But we did. And a number of times, Steve and I told ourselves, worst-case scenario, we learned something new. We’ve got an interesting Wikipedia page, whatever. But in our hearts, we want this thing to be cool and great. And we want people to love it.”

If hardware-based surprises were out of reach, then it would be the software that could deliver them – literally, every Monday, via WiFi. Engineer Dan Messing had been working on Playdate’s software development kit, and Panic had hired Shaun Inman (experienced developer and tiny-game enthusiast) to start creating the first titles. “But we couldn’t make enough games,” Sasser says. “And so we sat down in the conference room with a big stack of note cards, and a big fat Sharpie, and just wrote down the names of all the people who inspire us, or make games that we think are cool, or who just are doing work that we love.”

They began to imagine a dream sequence of games from their favourite developers, pinning up cards on the corkboard: names such as Terry Cavanagh (sadly, too busy to take part in the project), Bennett Foddy and Keita Takahashi. Panic’s work on Firewatch had positioned it well to pitch to some of its creative heroes. “We’d proven we were semi-capable of doing things,” Sasser laughs. “But the thing that blew me away, and this is a testament to these game developers, was that we came at them out of the blue with this wild thing, and they’re immediately excited by it. I’m sure they had some reservations in the back of their mind. ‘How many people are really going to get to play my game? Is this really going to work?’ The same things that we felt the whole time – but it didn’t stop them from diving in. And once they learned about the crank, then a billion ideas just poured out of their brains immediately.”

"He showed up with a game that was in a genre that I don’t think we even imagined, and had this beautiful hand-drawn art that was beyond anything that we had created."

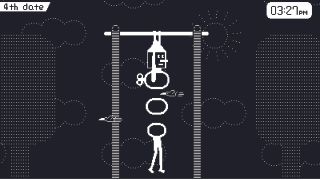

It was the next source of great inspiration: letting these world-class developers loose on Messing’s SDK, on a 1bit screen, on the crank, and watching what they came up with. Takahashi, naturally, was immediately enamoured with the bizarre little input method, developing a game with crank-only controls. With Inman’s help on the programming side of things, this would eventually become Crankin’s Time-Travel Adventure, a game in which you turn the crank to jog the perpetually late Crankin to meet his long-suffering date. The faster we crank, the quicker he runs: when we turn the crank the other way, time reverses and so do Crankin’s movements. In this way, we’re able to dodge obstacles (butterflies, rampaging pigs, the inevitable sentient pile of faeces) by positioning him at advantageous points in time. When hanging from a bar with his body stretching into pieces, darts fly safely through the gaps, for instance. It’s delightful, a silly yet sophisticated feat of analogue control engineering and programming, something akin to indie darling Braid or the more recent The Gardens Between – the only game Takahashi played in 2018, apparently, after noticing it did similar things with time manipulation.

This is no mere Game & Watch fodder, then. “A lot of the game developers, of course, are perfectionists,” Sasser says, “and don’t want to show their work until it’s further along.” Panic would trust them to do their thing, and then months later see an unexpected animated GIF of a particular game pop up in their Slack channel. “Chris Makris was someone that Neven was aware of who was making really cool games – he showed up with a game that was in a genre that I don’t think we even imagined, and had this beautiful hand-drawn art that was beyond anything that we had created. And that was one of those moments where the GIF arrives and we’re all popping up from our desks, looking at each other, like, ‘Oh my god, you’ve got to refresh this right now!’”

The list of developers making games for Playdate’s first free season (12 games in total) comprises some of the indie dev scene’s best and brightest. And although we’ve been permitted to reveal some of the names, we’ve been asked to keep the contents of most of the games a surprise. Suffice it to say that what we’ve played so far is encouraging stuff, an eclectic mix of genres and ideas – some using the crank, some forgoing it – of varying length and complexity, and spanning many art styles. They feel intimate and personal, more than anything: thanks to the 1bit screen and accessible scripting language Lua, devs who might not usually handle certain aspects of development such as art or programming themselves have jumped in with both feet.

Tantalising, we know. But that’s kind of the point. As someone who’s had a lifelong love of videogames – ever since he pulled the blanket off an Atari 2600 hidden in the back of his parents’ station wagon as a young child – everything that Playdate is “comes back to people who love videogames,” Sasser says. “These are people who love games, and we love videogames. And creating videogames is such an awesome and powerful thing. So for us to even just be witnesses to the stuff that was happening was very cool.” So much that’s joyous about games is about secrets, about surprises –something that’s increasingly difficult to achieve in this day and age. (Indeed, Panic and its selection of devs have struggled with it: when you’re used to the validation that comes from posting updates online, going without it can be tough. Threes developer Asher Vollmer decided to release his Playdate game, Royals, rather than wait for the handheld’s release; Takahashi, meanwhile, hasn’t been able to resist teasing animations from Crankin at his art shows – separated from the context of the console, of course, but still wracking plenty of nerves at Panic.)

The importance of surprises in an always-on world

“That’s part of the reason why we wanted to keep this a secret,” Sasser says. “Just because nothing is a secret in 2019. When I was a kid, there were barely videogame magazines. There certainly wasn’t YouTube. And there was no way to know what a game was going to be, except to pick it up off the shelf and flip it over and look at two screenshots.” He’s keen to stress that Playdate isn’t about nostalgia. “But there was definitely something in that anticipation of driving home, and looking at this box over and over again, and dropping the cartridge in. And sometimes the games were just incredibly bad. But sometimes they were even better than you could have imagined. And so there’s definitely an attempt to recapture a little bit of that magic that some generations maybe haven’t even experienced.” Secrecy, then, was key. They didn’t want to run a Kickstarter, or test the waters with a concept post on Panic’s blog. “We wanted this thing to come out of nowhere, fully formed, and just blow everybody’s minds,” he says.

‘Everybody’ is, perhaps, something of an overstatement. The new blockbuster console this is not: it’s a goofy, pseudo-retro handheld curiosity. The final product is of the expected level of Teenage Engineering quality, but this also means units have been expensive to make; a Playdate complete with USB-C cable and that first season of games will set you back roughly £115, and Panic is not making a large profit above the unit cost. And unless you’re a die-hard fan of the indie- game scene, plenty of its star devs may not even register your interest. Mercifully, Panic and its collaborators are under no illusions about Playdate’s niche appeal. Indeed, when we ask the devs we speak to who Playdate is for, a couple half- jokingly tell us that it’s probably for Panic themselves.

Sasser woke up to a Facebook message from Mark Zuckerberg expressing interest in buying Panic. “This is going to sound so bad,” he giggles, “but I didn’t reply."

They’re not far off the mark. “Even with our FTP client [Transmit],” Frank says, “we’ve always sort of been our own first customers. Like, ‘What would we like to see in this? What would we use? And what would be delightful to us?’ That’s sort of our guiding light for everything we do. It’s confusing to a lot of people, because they’re hung up on, ‘Well, how are you going to make money?’ I don’t know – and honestly, I’m not entirely sure how we’ve done it for the last 20 years.” He laughs. “But somehow it seems to keep working out.”

Panic has always been steadfastly independent – “like, maybe to a fault”, Sasser laughs. Playdate, it seems, is partly a statement of intent. Not so very long ago, Sasser woke up to a Facebook message from Mark Zuckerberg expressing interest in buying Panic. “This is going to sound so bad,” he giggles, “but I didn’t reply. Like, this is not what I want. What? No, thank you. There could be a time when we reach the end of our road, and we run out of ideas and money. But we have avoided that like, aggressively. And any time I see a company in the software world pop up and make something, that’s super-inspiring to me. Then they’re immediately acquired by someone else and you never hear from them again. That voice is gone. And it kills me.”

With Playdate, then, Panic has taken the opportunity to use its resources to make something emblematic of its values. “There’s definitely a thing where businesses today, especially in Silicon Valley, are just these little factories that exist to make a single thing, and they don’t even really care about that thing,” he continues. “They just need to kick money back to the people that gave them money in the first place. And therefore it’s a success. So all of the people that work for those companies are checked out. How much can you care when nobody above you cares?”

Like Nintendo making a copy machine in 1971, Panic making Playdate might not be a particularly logical endeavour. It exists to cheerfully disrupt, in a way – perhaps just make the suggestion of a disruption. “And maybe that’s why we’re put on this planet: to be an example of like, you can move slowly. Make sure you have enough money in the bank, make something good and see what happens. You don’t have to go for world domination and crush your enemies like, ‘We’re going to be the number one fuckin’ juice maker’ or whatever.” He laughs. “The point is, this is something I believe very strongly in and it kills me to see voices disappear. I get so inspired when people do crazy things like this. It makes me want to try crazier things, and I feel like that feeling is fleeting and hard to find. And I do wish it existed more. So we’ll just do it ourselves.”

So here it is: this odd little WiFi-compatible, 1bit game machine with a crank. It’s designed to make you wait and wonder. It’s made to pull you away from whatever you’re doing on your phone for five minutes of fun, and purpose-built to prompt radically new types of games and ideas from whoever ends up making software for it – and when the SDK is released into the wild among the Bitsy and Pico-8 enthusiasts, you can bet that the exclusive developer pool will get a lot wider and weirder. (When that will be remains to be seen, but the current plan is to ship the console itself later this year: you can register your interest now on Playdate’s official site, with preorders opening this autumn.)

So what does success look like? “This is what I struggle with,” Sasser says, “because this whole thing has been an adventure for us. And it’s hard to talk about that part without sounding trite and clichéd.” Yes, Panic has learned a lot, has grown as a company and people, and the journey was the friends that were made along the way – Sasser’s being deliberately tongue-in-cheek. “I never imagined that we’d have gotten this far, so half my brain is like, we’ve already set up to accomplish what we want to accomplish.”

On the other hand, of course, this is a business, and Panic does want to see Playdate succeed. “I would love for this thing to explode in sort of a mini-cultural moment and find an audience that really resonates with it. And I feel like there’s a chance that that could happen. I can’t guarantee it. But in my heart, I feel like it will find its place.

“So it’s difficult for me to answer,” he continues. “It’s kind of cheap to say, ‘Oh, we’ve already won’. So whatever happens, happens – the true answer is, I really think that there are people like us and like these game developers who are going to just have their minds blown by the existence of this device. And they’ll be so excited to hold it in their hands and play games and make something for it, or just see what other people made. We can’t be alone. How many people that is, is a fair question. But I’m really confident that those people exist, and that the thing that we’ve created is irresistible to them, and they want to be a part of it. If we could just find that group, then that’s a success to me.”

It’s counterculture, perhaps, in a friendly yellow form. It is different for the sake of being different. “I don’t think we’re really sweating if this doesn’t sell – nobody loses their house, and we wouldn’t make that kind of bet,” Mrgan says. “But we do think it will be cool.” He points to Teenage Engineering’s similar viewpoint. “‘They make a keyboard for how much? I can buy one at Target for $40’. Like, it doesn’t make sense on paper. But it doesn’t have to. People fall in love with things. And there just have to be enough of those people who are happy and continue being happy. We’re not Unicef, we’re not saving lives out there. But to the extent that a piece of entertainment and technology, and maybe a little bit of art can make you happy, we’re trying to do that.”

From its inception as something to shake Sasser out of an existential crisis, to its function as a continual source of surprise, Playdate has always been aimed at a particular audience. “We’re building this for people who love videogames,” Sasser says. “People who will never forget burning the bush in Zelda and uncovering stairs to a dungeon, or people who remember laughing uproariously as they roll the ball of stuff in Katamari, or even people who got chills when they were riding their horse in Red Dead Redemption towards Mexico and that song started playing. People who play Firewatch one week or Uncharted the next – they don’t care about the platform, and they don’t care about the genre, or the number of ‘A’s, they just care about that indescribably electric feeling of experiencing something new that games give us. That’s been with me my whole life as I played videogames. So Playdate, in a way, is a shrine to that feeling.”

Getting back in touch with that sense of reckless curiosity has been a balm for him, personally. “Things were not great for me, and running this company now, I feel almost like a different person,” Sasser says. “I feel like a huge part of that is finding again how important it is to me and for everyone here to just make things, and be proud and excited about it. And that’s why we exist. I don’t know, it’s so weird for me to calibrate. Because that’s actually kind of preposterous, when I stop and think about it.” He pauses, and laughs. “The whole thing is kind of preposterous, when I stop and think about it. But it’s just what we do".

Subscribe to Edge Magazine for only $9 for three digital issues and show your support for long-form game journalism

Jen Simpkins is the former Editor of Edge magazine, and is a multi-award-winning creative writer. In her most recent industry role, Jen lent her immense talents to Media Molecule, serving as editorial manager and helping to hype up the indie devs using Dreams as a platform to create magical new experiences.

Most Popular