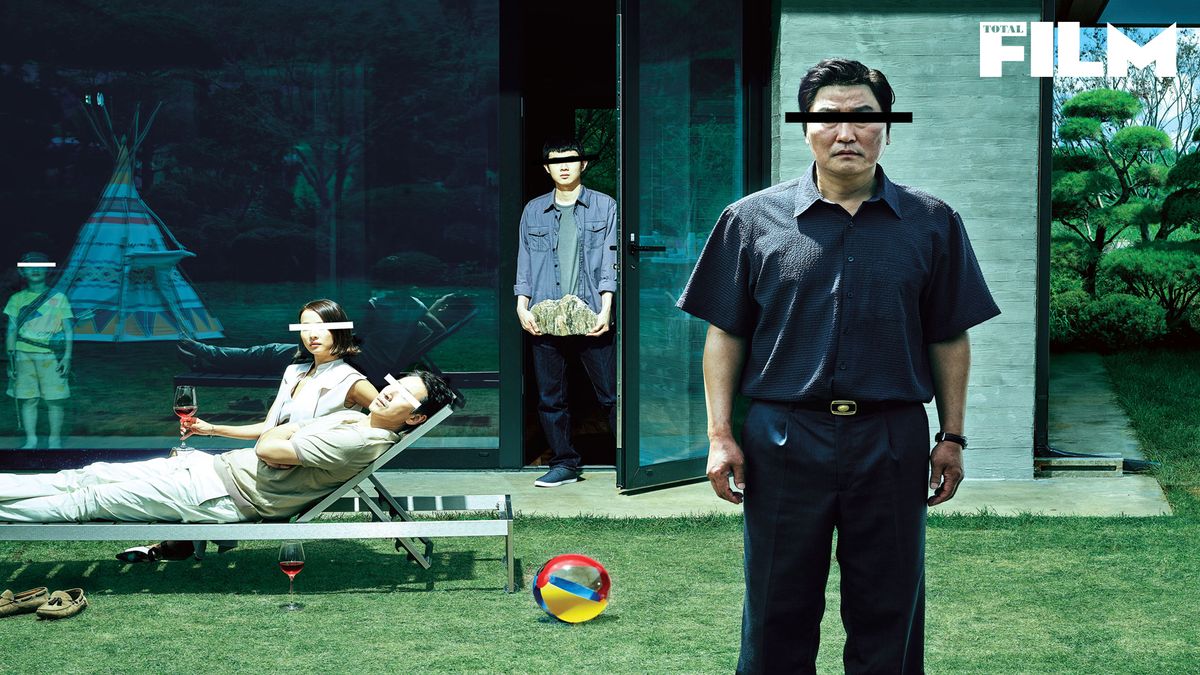

The making of Parasite: Bong Joon-ho talks satire, social inequality, and staircase cinema

Bong Joon-ho speaks with Total Film to discuss the making of his masterpiece, award-winning black comedy-thriller Parasite

As Bong Joon-ho arrives at a beachside restaurant in Cannes, he has an announcement. Or at least his translator does. "He wants to talk more about soccer with you," she says, chirpily. The South Korean director behind Snowpiercer and Okja is seemingly more interested in the upcoming Champions League final between Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur than talking up his new movie, Parasite. "I'm supporting Sonny," he grins, referring to Spurs' own South Korean star, Son Heung-min.

While Son will ultimately end up empty-handed (sorry, Spurs fans), Bong will not. By the end of the week, the Cannes Film Festival jury unanimously award Parasite the top prize, making Bong the first-ever South Korean to take home the Palme d'Or. "The film is such a unique experience, it's an unexpected film," commented jury head Alejandro González Iñárritu, a neat summation of a work that brilliantly straddles arthouse and mainstream with a daring mix of black comedy and social commentary.

Get inside access to the world's biggest and most interesting movies every month by subscribing to Total Film magazine in print or digital, including reviews of every film released that month, from blockbusters to indies and cult cinema.

The seventh movie of an increasingly extraordinary career, Parasite has become Bong's biggest hit worldwide; at the time of writing it's taken $167.6 million (becoming the highest-grossing South Korean film in the process) – eclipsing his previous best, 2006 monster movie The Host. In America, it's the highest-grossing foreign-language film of the year, making history at the Academy Awards as the first foreign-language film to be awarded the coveted Best Picture prize – it also picked up awards for Best Director, Best International Feature Film, and Best Original Screenplay.

While Bong, 50, has often worked in genre cinema – be it crime (Memories of Murder, Mother) or fantasy (Snowpiercer, Okja) – Parasite is a very different beast. The story of the poor Kim family (headed up by Bong regular Song Kang-ho), it begins as the son, Ki-woo (Choi Woo-sik), gets a job tutoring English to the daughter of a wealthy tech CEO, Park Dong-ik (Lee Sun-kyun). Soon enough, others in the Kim family, via less-than-legitimate means, find gainful employment in the Park's luxury household.

Bong also tutored for a rich family when he was in college (he studied sociology at Yonsei University in Seoul). "The sequence that depicts when he enters the house was pretty similar to what I experienced," he says. "I grew up in a middle-class family that's in between the poor and the rich family in this film, but despite that, when I first entered, I had this very eerie and unfamiliar sense of this house. Actually, they had a sauna on their second floor – at the time it was quite shocking to me!"

Mind the wealth gap

Nevertheless, the director didn't dream up Parasite until he was in the complex post-production for Snowpiercer, his 2013 dystopian sci-fi about the haves and have-nots riding on a perpetually moving train through the Earth's second Ice Age. "Snowpiercer was about class struggle and class difference," says Bong, pointing out that the film deals with struggles between the elite in the train's luxury front carriages and those bringing up the rear. "This time, I think I wanted to talk about the gap between rich and poor – a similar theme – in a more realistic way, and on a smaller scale."

On the surface, the contemporary-set Parasite does look simpler than Snowpiercer and even Bong's last film, 2017's Netflix-backed Okja, the story of a 'super-pig' developed by a multinational specialising in genetic engineering. "In Okja, you have around 300 [VFX] shots of the pig. Not only did that require a lot of money, but also incredible energy as well. But with this film I was able to spend that energy on the characters and the nuance… I felt like I was able to look at the film through a microscope and pay attention to more details."

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

While he'd broached social inequality in his films before, Parasite did mark a first for Bong. During the shoot, the film's cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo – who previously shot Snowpiercer and 2009's murder-mystery Mother – remarked to Bong: "This is our first time filming rich characters," Bong explains. "Even in Mother and The Host, my films have always featured quite poor characters... This was our first time filming a rich family and a rich house. Even Captain America [star Chris Evans]… he was dressed in rags in Snowpiercer!"

Originally the film was called 'The Décalcomanie' – a reference to the artistic concept of 'decalcomania' or 'decal', where an image is created and can be transferred, or reflected, onto another surface. But Bong changed it to its less-pretentious title, though one that may not necessarily refer to the Kim family. "In the story, they are conmen and they do bad things, but they're not really the true villains. They're characters in this grey area. I'm more or less focused on the situations and the horrible system they're in that forces them to be the parasite of this story."

At one point, Song Kang-ho's patriarch pauper Ki-taek reads about how 500 college graduates applied for a lowly security-guard position – a fact Bong took from a real-life article. "The poor characters in this film are actually quite smart and capable. You think that with those skills and abilities they would do pretty well if they had a job, but the issue is they don't have a job – there is not enough employment for them. And I think that's the economic situation that we face in Korea and also across the world."

"The production designer took my sketch to an actual architect for advice, and they said, 'No one builds houses like this, architecturally! This is ridiculous!'"

Bong Joon-ho

As the Kims' systematic infiltration of the Park household takes place, Bong was keen to look at how money matters impact on a family, and how desperate it can make you. "The economy is something you really feel," he says. "It's like right next to your own body." Films he watched during pre-production? Joseph Losey's The Servant (1963), with Dirk Bogarde engaging in power dynamics with James Fox's employer; Claude Chabrol's This Man Must Die (1969); and Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid (1960), a domestic horror-thriller that'd give Fatal Attraction a run for its money.

This latter film, which features a key sequence set around the stairs in the family home, was particularly influential. "We like to call Parasite an example of 'staircase cinema'," explains Bong, "because the staircase is very important in the story, and that is definitely one of the influences by Kim Ki-young." Yet, it's not just the staircase that matters in Parasite. The Park house – where much of the action takes place – is a brilliantly designed playground, subtly explored in the film's first hour in ways that impact the second half.

A director who thinks visually – he even draws all his own storyboards – Bong figured out the basic structure of this modernist open-plan living space by the time he'd written the script. But his designs were for a story that, without venturing into spoiler territory (seriously, you must see the film for yourself), involves a lot of sneaking around from various characters. "This idea of visibility and non-visibility within the house was very important. So the production designer took my sketch and took it to an actual architect for advice, and they said, 'No one builds houses like this, architecturally! This is ridiculous!'"

The intricately designed house – eventually constructed on a soundstage – even features a bunker, built by the rich for protection against their trigger-happy neighbours in North Korea. Is this really a concern? "Mostly Koreans, we don't really think about it. Of course we are afraid of war and we do worry about it but we just go on with our daily lives. Because ultimately there is nothing we can do." What about his house? Does he own a panic room?

"I live in a very normal apartment," he grins. "Dig down and it's the house below!" Elements like this reveal the jet-black humour that snowballs in Parasite's wildly unexpected second half, as the Kims' plans unravel. "When you see events unfold, when you don't expect it at all, you feel very flustered and I enjoy that sense of being very flustered," says Bong. "I'm a little hesitant to say this – because I don't want to seem too much of a pervert! – but when the audience is laughing at these scenes, at the same time they doubt their own laughter. Can I really laugh? They almost feel sorry that they're laughing about these scenes, and that's what I really enjoy."

Home comforts

After the more internationally flavoured Snowpiercer and Okja, did he revel in being back on home turf? "I don't necessarily divide projects into one that's for a Korean audience and one that's for an international audience," he says, "but I can't deny the fact that I get a lot of joy from just creating a story where I, as a Korean, depict situations and details that a Korean audience would fully understand, and we would share a laugh with these details. Of course the audience laughed out loud when we screened at the Lumière [in Cannes], but in Korea we'd have 10 per cent more laughter!"

Regardless of this, given the success in both Cannes and in the US, it seems Bong has finally delivered his breakout movie. Perhaps it's about time. Snowpiercer endured a torrid time, with Bong clashing with Harvey Weinstein, as they wrangled over running times and content (with the disgraced producer later refusing the film a nationwide US release).

As for Okja, as one of two Netflix titles in Cannes competition in 2017, it became embroiled in controversy, with French theatre owners protesting against its inclusion in the festival. Parasite, however, hits more universal themes in a domestic setting we can all relate to. "I get more excited when I have these limitations – very enclosed, almost claustrophobic spaces," he says. "I get anxious when I feel like I have an infinite number of spaces where I can pick and choose." All round, it's been an experience that will influence Bong's career to come. "I'm looking to pursue films more of this size in the future," he says. Whatever he does, the spotlight will be on him.

This feature originally appeared in Total Film magazine. If you subscribe to Total Film, you can save up to 36% on the price of the physical product or up to 45% on the digital edition.

James Mottram is a freelance film journalist, author of books that dive deep into films like Die Hard and Tenet, and a regular guest on the Total Film podcast. You'll find his writings on 12DOVE and Total Film, and in newspapers and magazines from across the world like The Times, The Independent, The i, Metro, The National, Marie Claire, and MindFood.