Max Payne turns 20: Remedy Entertainment looks back on the making of its iconic action game

Here’s how Max Payne was made, from the people that were there at the time

From 2001 to 2003, it wasn't just a third-person camera that made the world revolve around Max Payne. Nor was it the mere sight of its excellent graphics, or of PCs taking a sideways leap into console land from where they would never fully return. More than anything, it was the man. A propulsive thriller made by just two dozen people in Espoo, Finland – a "garage band", according to writer Sam Lake – it was the story of a man imploding. The door opened on that scene of devastation, the wife and newborn child slaughtered by drug addicts, and in one New York minute gaming had acquired a new thirst for revenge.

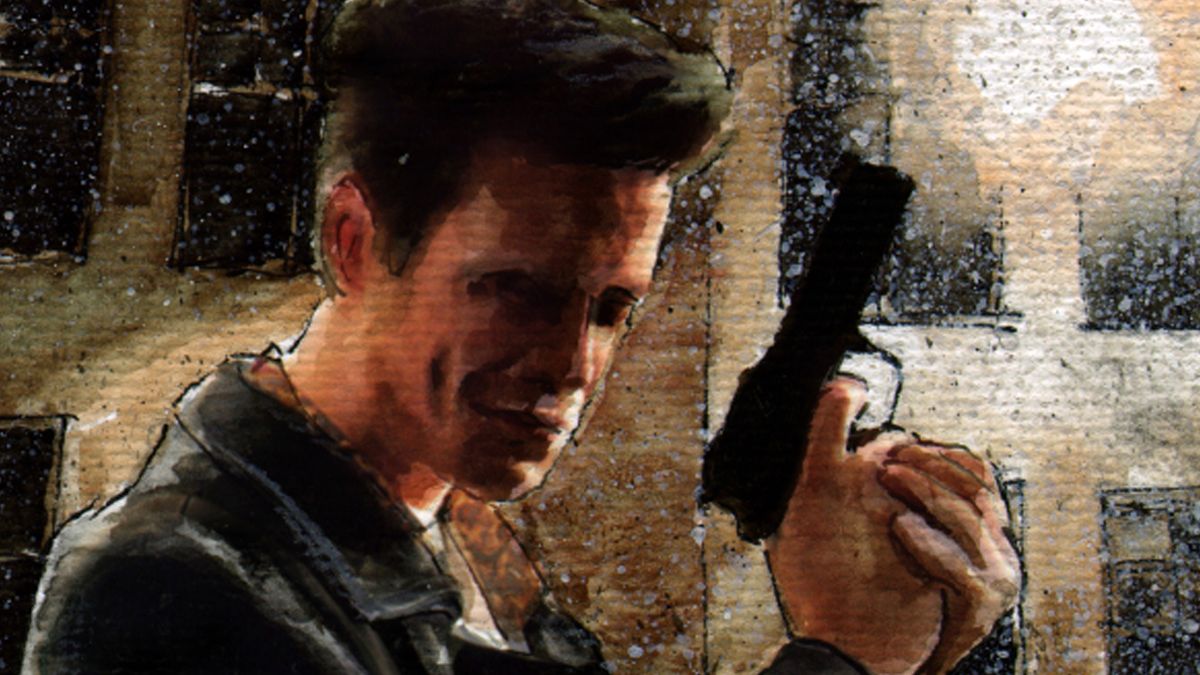

"For me, the starting point was this archetype of the private eye, the hard-boiled cop," says Lake, whose portrait need never be printed so long as Max, for reasons you either know already or will soon learn, appears in a screenshot. "The team wanted images and ideas seen in countless action and crime movies, even in pop culture generally. Just something that hadn't been seen much in games."

"John Woo had this action where all this trash was flying in the air – we just wanted that style," says programming lead Olli Tervo. "Lots of things had to be happening." "One of the first things we did technologically was the particle system," adds Sami Vanhatalo, the game's lead technical artist. "And once you started seeing the particle effects with this huge slowdown it was like: 'God, something good must come of this.'"

Lake, however, was concerned more with the bad – the creeping, contagious bad of a modern film noir. He wanted a "deeper, more psychological" story than existed in action games of the time, something preoccupied with both outer and inner turmoil, the city as well as its people. Much of what sets Max Payne apart today is the quite alien, Scandinavian air that rips through its New York streets, rapping on its windows as an impenetrable blizzard devours the skyline. Ragnarok, the Norse vision of the end of the world, was as natural an association, suggests Lake, as any squalid crack den or alleyway.

This making of Max Payne feature was first printed in Edge #195, 2008. You can purchase new issues of Edge at Magazines Direct or find information on Edge #361 here.

"Max's journey is a revenge story about a man who's been pushed so far into a mad, impossible situation that normal, everyday life has lost its meaning. It's disappeared. So you couldn't describe what was happening in that context – or at least Max couldn't. All that's left are archetypes and metaphors, monsters and demons. It becomes a myth. So it felt like the right thing to do to bring all those references to it." Plus, as we remind Lake, no small degree of comedy – not something you'd automatically find in discarded needles, dead babies, and baseball bats. "We didn't want to avoid that over-the-top feel because the player is going to create comical situations in any case, always. Humour is a natural part of playing games and, as a writer, you're always trying to match the gameplay experience. If you're too serious about it, that simply doesn't happen."

Development of Max Payne spanned several years, with '96 and '97 seeing the leap from Quake 2-era 3D accelerators to cards capable of, as Remedy would discover, near-photographic realism. Until technology intervened, the game was a more cartoony affair drawn entirely by hand. "But if we wanted to set the game in, say, some sleazy motel in New York, we needed some kind of reference," says Vanhatalo. "We'd already sent the art guys to some really nasty neighbourhoods with a couple of bodyguards, and then we realised that we had all these photos. Why not use them as the basis for our textures? There were a lot of art tricks you had to do to get those textures to work: getting all the unnecessary light information out, for example. But once we'd decorated part of the game, everyone was like: 'Wow. This is what we've been trying to make.'"

Well, not quite everyone. To some, explains studio co-founder and development director Markus Mäki, the arrival of real-world textures felt less like the start of something than the end. "To them, you weren't an artist any more if you did something like that. But if you're basing things on the real world, it's just the sensible thing to do." Were there ever fears that it wouldn't work? "I don't think that was an option."

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Turning a page

Lake had already pitched the idea of using graphic novel panels for the game's cutscenes, casting himself in several 'heavily Photoshopped' examples. But the advantages, says Mäki, already spoke for themselves: "With a graphic novel, the nuances are there in the head of the reader, and it would be much harder to reach that level with in-game or even prerendered cinematics. Now you can do that stuff believably; back then it was a different ballgame. And there was the other reason: production.

"We did a lot of streamlining and reorganisation of the story anyway – but once you had the graphic novels you could cut them up, put them on walls, follow the whole game and say: 'You know, that should really be there'. And in 30 seconds you'd made a dramatic plot change. Even if it meant redoing some of the imagery, you were talking a day or two instead of a week of doing cinematics."

Fans and critics know only too well, of course, the side-effect of Lake's proposal: a fourth-wall shattering twist worthy of Stephen King, which saw the writer awake one morning to find he'd become his character. "We were still talking about this rise of photorealism and at the time it didn't feel like a big deal," he admits of having his own face wrapped around Max's polygonal chunk of a head. "With all these hand-painted pictures, no one would have recognised me anyway. Fast-forward a couple of years to the end of the project, though, when we're using photographs for all the textures in the game, and there I was. At that point, the idea might have given me pause."

He insists it was fun, however, with his expanding role including casting many of his friends and relatives as the game's crooked line-up of cops, executives, politicians and thugs. "And if you look at us, we're not exactly Italian mobsters," admits Vanhatalo. "So we were like: 'Quick! Check out the guy delivering the pizzas. Get him over here for a while'." The game's credits, we're told, are a cornucopia of cousins, fathers and girlfriends, with the occasional industry figure tossed in. One is now CTO at AMD.

"I was walking home when a car stops in front of me. Two climb out and shout at me to stop. They proceed to ask me if I'm Max Payne; they want my autograph"

Sam Lake

Is Lake recognised in the street? "At trade shows like E3, mostly, where I'd been doing countless demos of Max Payne or Alan Wake. There was this one time a couple of years ago when I was walking home from the office in Espoo; it's a nice neighbourhood, but the street was totally deserted apart from me and this car. It slows down and I see these four guys peering out of the window. Then it turns round, passes me again and stops in front of me. Two climb out and shout at me to stop, and by this time I'm nervous enough already. Then they proceed to ask me if I'm Max Payne; they want my autograph. It happens rarely, luckily enough. Finns are reserved people. We rarely talk to strangers.

"The whole thing did end up being quite a lot of work, though. That was one of the reasons I didn't want to do it for the sequel, because the schedule was much tighter and there was much more story. The screenplay of the first game was something like 150-160 pages – for the sequel it ended up being 600. It didn't make any sense to waste a month or more of precious writing time for those photo shoots again. First time around, we didn't have a choice."

A logical progression at a glance, with better physics, acting talent, and the obligatory combo moves, Max Payne 2 was an altogether different proposition for its creator. Take-Two's purchase of publisher The Gathering had muddied any prior relationship with Rockstar Games, whose interest had nonetheless produced valiant, difficult ports of the first Max Payne for consoles. Now, the obstructions were gone.

"They're a very eccentric company that works in strange ways," says Vanhatalo. "But surprisingly compatible. I don't recall a single instance where someone was trying to steer us into doing this when we really wanted to do that. We were on the same page the whole time."

"I do remember some Stranglehold-esque proposals from one of the Rockstar producers, for Mexican stand-offs, stuff like that. But the time really wasn't right," adds Mäki. "But we both wanted to go higher on the production values and be more ambitious with the story. They're straightforward and honest guys: they expect a lot but deliver a lot when you need them. After five years of working with them, I don't think anyone has anything bad to say."

The Fall of Max Payne

While Remedy set about introducing its high-flying particles to early Havok physics, Lake was left to wrestle with the more obvious dilemma: now what? What next for the cop who had destroyed the world of his enemies – just as they'd destroyed his – only to find himself stood atop the rubble? In the darkly titled The Fall Of Max Payne, we learned the answer: if life couldn't get any worse for Max, it could certainly get more complicated. Did the introduction of Mona Sax, the femme fatale in a grander, murkier and more open sequel, pose problems for a story that was, at its best, about the isolation and disintegration of just one man?

"I did worry, and I did struggle," Lake admits. "The main reason was Max's narration, his internal monologue. That was a very important tool to tell the story, maybe the most important one. Through it, we get to know what Max thinks and feels. He's not an empty vessel. I did want to switch to Mona [she later became a playable character] – in fact, had there been more time, it would have been nice to add levels where you play as Vinnie, Vlad and Bravura – but it was problematic. In the end, Max frames those sequences with his narration, saying that he doesn't know exactly what happened, or what Mona did, but it must have been something like this. In other words, when you are playing Mona, you are actually experiencing Max's guess of the events."

Boasting an understandably superior lead performance from Timothy Gibbs, a professional actor, the game reviewed well, ported admirably to PS2 and Xbox, and has since helped the series achieve sales of over seven million copies. But not everyone allowed the drama and spectacle to excuse the unwavering action epitomised by Max's slow-motion leaps. EDGE magazine, notably, scored the first game six out of ten.

"We're firm believers in focusing on something," insists Mäki. "I'm not sure you could do it quite so focused nowadays, as people's expectations have grown, but it was deliberate. Deliver an experience and deliver it well."

"And we've always been very aggressive when cutting stuff out of a game," says Vanhatalo. "We've never been fans of having to backtrack through the level to get the red keycard, for example. That whole 30 seconds thing [a reference to Halo's self-professed recycling of action moments] is often called the core loop – and that was our core loop. A good recent example would be something like Call Of Duty 4: you pretty much do the same thing but with a different gun in a different place, but it nails the core loop so perfectly that you never tire of it."

20 years on from the release of Max Payne, its impact is still reverberating throughout the videogame industry. Its influence can still be seen driving Remedy Entertainment too, with the company injecting its propensity for kinetic combat systems, smartly-crafted storytelling, and photorealistic visual design into everything it has done since: Alan Wake, Quantum Break, and Control. But perhaps most importantly, Remedy has continued to create what Lake calls “strong leads", making games that don’t just point its camera at a character, but look at them directly, creating more than just a player-inhabited shell. 20 years later, that’s perhaps the most important legacy that Max Payne left behind.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.

EA says Mass Effect 5 is now BioWare's "full focus" as it shuffles devs to other studios, with some reportedly facing layoffs following Dragon Age: The Veilguard's underperformance

DRM-free store GOG launches a new way for fans to influence which games get preserved "forever," and players are going to bat for Diablo 2, OG Final Fantasy 7, and a pile of cult classics

Most Popular