Love GTA, Heavy Rain and Resident Evil? Well Deadly Premonition is better than all of them. Here's why

You probably haven't played one of the best games of this generation so far. Here's why you should

You will rarely have felt closer to a lead character. Fact

Character attachment is a bigger problem than you’d think in modern gaming. And there’s no genre in which it’s a bigger issue than the narrative-driven sandbox game.

The problem is this: In any game, for the narrative to be truly effective in terms of video game storytelling (which is very different, in terms of both mechanics and the effect it can have on its audience, from movie storytelling), the player must be bonded with their character on as close to a 1:1 level as possible. With current technology, that goal is impossible to attain. Monitors, controls, and anything less than a dirty great Matrix jack right into the back of the head all see that the player is aware of their physical separation from their character. Even in first-person. Even with the biggest wraparound monitor set-up in the world. Even with the most immersive storyline and the best acting in the world, you’re still aware, even subconsciously, that you’re operating a keyboard and mouse or a controller. And that constantly reminds you that you are not Gordon Freeman, and you are notJack from Bioshock.

There are ways to greatly limit that though. Valve, in particular, excels in this area. Its silent protagonists never alienate you with words or actions that you yourself wouldn’t say or carry out.Valve's lack of third-person cut-scenes ensures that you’re never pulled out of the main gameplay perspective,and its refusal to pre-render anything means that you're never divorced from the world.Its ambient storytelling through little details hidden within the environment makes sure that the player’s understanding of the game world is always at the same stage as the character’s at any given point in a story, and most cleverly, the way that the House o’ Gabe manipulates emotional and dramatic peaks and troughs to incite reactions and create empathy with a character’s situation ensures that in a Valve game, to put it plainly, you are not actually playing a character at all. That character is an extension of you.

The upshot of all of this technical rambling? Most sandbox games have a real problem with storytelling, because most of them do the opposite of everything listed in the previous paragraph, and compound all of the problems listed in the paragraph before that. The issue comes from the fact that in a genre (supposedly) so inherently built around the player’s freedom to do whatever they want, whenever they want, trying to tie in some kind of prescribed identity for the lead character is nearly always at odds with the identity the player creates for themselves. Red Dead Redemption does alright, by making JohnMarston a fairly ambiguous type in terms of morals, but Grand Theft Auto IV fails pretty badly a lot of the time. A protagonist who repeatedly professes a desire for a quiet, peaceful life of repentance, in a game which continually encourages the player to cause havoc and destruction wherever they go? It just doesn’t work.

Above: Agent Francis York Morgan. Your new best goddamn friend

How does Deadly Premonition get around that? How indeed, does it go beyond that, to create one of the most solid player/character bonds around while maintaining the character integrity of one of gaming’s most quirky and unique protagonists through a raft of non-interactive, third-person cut-scenes? It does it effortlessly, with a neat bit of gameplay trimming and a little stroke of genius called Zach.

The trimming? When exploring the world at large, your options are somewhat limited. No lead-blazing rampages here. Much like the way that L.A. Noire limits the possibility of your creating a graveyard’s worth of collateral damage every time you drive down to the shops for a pint of milk, in Deadly Premonition you are not going to be shooting up the whole town on a a whim. You just can’t do it. And why would you? You’re an FBI agent, fuggodsake.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But you never feel hampered in your freedom by this. Because Deadly Premonition does a great job of making sure you want to stay in character. Aside from masking your inability to shoot passers-by, by way of some plausible narrative justification for the town’s quiet streets, the game bonds you with Agent Francis York Morganvia of one of the cleverest and most rewarding player/character relationships in current gaming.

Above: York will grow a beard if you don't shave for a while. And start to smell if you don't change suits every so often. But it's not annoying, You'll want to look after him. Please look after him. He's awesome

York, you see, has a split personality. His literal other half is called Zach. York and Zach remain very separate people, meaning that York never succumbs to the control of another personality, but both live inside York’s head, and we’re frequently treated to wonderfully written conversations between the two, of which we only ever hear York’s half.

Did I say that York never succumbs to the control of Zach? That was a lie. Because while there are no schizophrenic breaks, and the character called York remains resolutely York within the reality of the game world, in a meta way, Zach is always in control of York. Because Zach is the player.

Well he’s not, but he is. You see the thing is that while within the narrative reality of Deadly Premonition, Zach is very much a part of York’s psyche, he, or rather the conversational gaps created for him by York’s dialogue, are written in such a deftly ambiguous way as to make the conversations between the two of them feel just as much conversations between York and the player. And crucially, there is never any conflict between the two.

York is completely supportive of everything the Zach/you hybrid wants to do. He’ll ask if you’re tired and want to take a break. He’ll tell you to let him know if there’s anywhere or anything in particular you want to check out. He’ll reassure you that there’s plenty of time if you want to ignore a story mission for a while in order togo exploring or finish some side-quests instead. This dialogue is both pre-emptive and reactive, laying open the gameplay options available and backing up any decision the player wants to make.

Above: I SAID LOOK AFTER HIM!

But because all of these conversations happen within a narratively cohesive justification which is established as existing within Deadly Premonition’s world early on in the story, none ofit breaks the fourth wall. Which is wise, because by definition that kind of narrative masonry demolition is designed to pull an audience out of a fictional reality. German playwrite and director Bertolt Brecht knew this. He used it on purpose to engage his audience’s critical faculties,and force them to consider intellectually the issues being presented during his work. But Deadly Premonitionmanages to dothat without excluding emotional attachment. It walks around the fourth wall rather than breaking through it, allowing direct player/character conversation while maintaining the narrative integrity of its world.

York will ask Zach what he thinks about certain situations and characters. He will reflect on in-game events the two have been through together, both intellectually and emotionally. He will try to solve the mystery at hand by talking it through with his unseen partner. He’ll fill the time on long drives with lengthy dialogues about the people and places around him, and somehow always manage to segue into some of the most deliriously, loveably nerdy conversations about classic genre TV and film you’ve ever heard.

Thus, you build a far closer relationship with York than you ever could by way of traditional third-person video game storytelling, because while you are York you're also alongside York. You gain the deeper, objective understanding of him as a person that can only come from being allowed to think of him as a separate, external entity, but at no point are you ever pulled away from the all-important sense that you’re not external from him at all. And all of this happens in a narratively cohesive way that never ever pulls you out of the reality of the game. It's a relatively simple method, but a stormingly clever one and powerful one, and it's rather staggering that I've never seen anyone think of it before.

Next: People are strange. And why that's a good thing

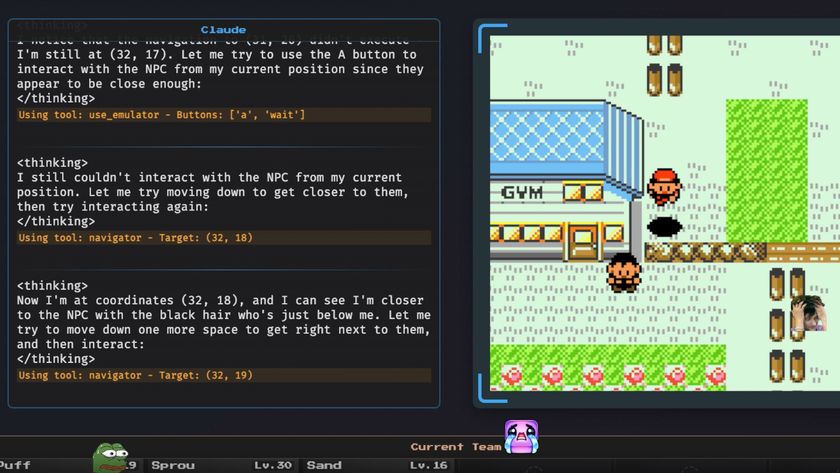

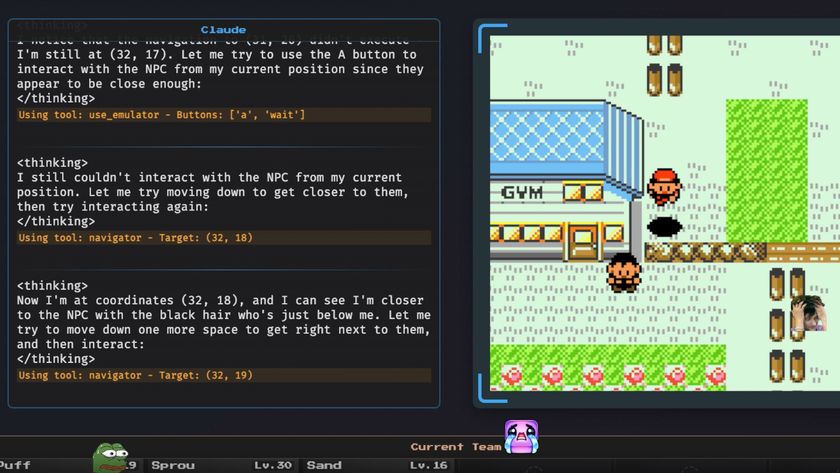

An AI's mission to 'teach' itself Pokemon Red is going as well as you think - after escaping Cerulean City after tens of hours, it went right on back

Pokemon Legends Z-A's visuals aren't "great" say former Nintendo marketing leads, but hope Switch 2 could allow Game Freak to "go back to the drawing board" and add more detail to future RPGs