Lore and The Order: How Dark Souls can fix gaming's storytelling struggles

Let’s begin with a chilling fact: the bricks in Super Mario Bros. are actually people, trapped in stone by blasphemous magic. Just think about it - while you’re merrily punching blocks for coins you’re actually pummeling the warped flesh of a living thing. That devastating bit of knowledge should completely alter the way you play the game, shouldn’t it? Of course it should. And of course it won’t.

Why? It’s Mario. You’ll still smash those blocks without the knowledge you’re freeing Mushroom People from an eternity of petrified despair. We know this because a) you’re already doing it, and b) smashing blocks feels lovely, like stepping on a semi-frozen puddle. As a man who valiant weaves through strangers to step on semi-frozen puddles, this is not praise I bestow lightly. But here’s the important bit: you’d only be aware of Mario’s hidden masonic torture if you read the manual (or listened to the same episode of Idle Thumbs which inspired this piece). Nothing in the game itself tells you.

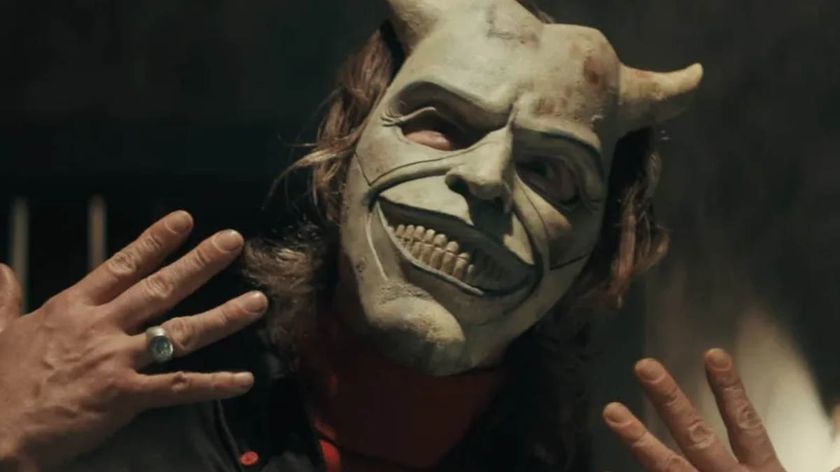

What does any of this have to do with The Order? More than you’d think, aside from a common thread of cultivated hirsuteness. Narrative is secondary in both titles: in the same way Mario is a compelling platform game given purpose via the long-rotted dangling fruit of liberating imperiled ladies, The Order is what happens when you start with beautiful moustaches and work backwards - a glorious game engine justified by something to do with werewolves, knights and werewolf knights. The connecting thread here being that games are, and maybe always have been, rubbish at telling stories.

If the secret history of Mario’s bricks tells us anything, it’s that Mario doesn’t need story to be a great game (and failing that, it’s a cool fact you can tweet to make yourself sound sexy and interesting) I don’t hate the Order - it’s fine, in the same way that eating cereal out of a handsome shoe is fine if you don’t have any bowls - but it’s especially wretched at telling a tale within the confines of being a game. By that, I mean that stories in games are at their best when they celebrate your efforts as a player; when you gain experience through agency.

Now, this isn’t a review of The Order - Dave has already done that here, and the bloodied gobbets are still clinging to his murderer’s hatchet - but it’s worth reiterating that this is something The Order simply does not do. Even with months of pre-release scene-setting, the world feels insubstantial. Crucial narrative threads are left dangling, key characters entirely forgotten. In The Order, things exist because they look nice; not because they’re clever or necessary or revealing.

What small interactive space the game provides for players to make their experience unique has no impact whatsoever on the way in which its story is inexorably unrolled. I mean, the game has you exposing an insidious, centuries-old conspiracy by looking in some cupboards. Cupboards. There are two problems with this: firstly, I don’t need to be inside a sumptuous, moist-browed facsimile of Victorian London to search through drawers full of other peoples’ shit; I can do that at work after the cleaners have left. Secondly, the whole scene is rendered numbingly irrelevant when an NPC ally finds the macguffin for you. It’s clumsy exposition by way of pointless exploration, and it’s indicative of the Order’s biggest problem: the harder it tries to be a cinematic experience, the less interactive it becomes.

Most damningly, The Order spurns every chance it has to enrich your experience through ambient storytelling or experiential play. You pick up bits of paper, expecting to find some dramatic secret scrawled on the back, only to flip it over and find beautifully-rendered nothing: like that scene in the Big Lebowski where the Dude searches for clues on a notepad, but instead finds the flowing delineation of a stonking great cock.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This isn’t a problem exclusive to The Order. Instead, it’s a reminder that our framework for narrative understanding is a cinematic one, conditioned through years of watching television and film. It took literally decades for movies to fully grasp what they did and didn’t need to show. By comparison, games are still in their infancy, still struggling to find the balance. Making them look and feel like films won’t always yield satisfying results. (You’re right to look red-faced, David Cage.)

But then perhaps a game like Dark Souls shows us a viable alternative. Dark Souls gets everything right that the Order gets wrong. I’d argue it’s the best example of games telling a story without ever leaning too hard on another medium. Yes, there are moments when you have to read things - thanks, books! - but they’re still presented in a profoundly gamey way. The narrative is spun so delicately into the fabric the world that you barely know it’s there, and yet everything exists for a reason: every brick, blade and blowdart is placed with intent.

Some of it is more traditional - or at least, as close to traditional as Dark Souls ever gets. The most useful example is Solaire, the buoyant Knight of Sunlight who helps you through the game’s toughest boss battles (except the Four Kings: screw you, Four Kings). There are gentle hints everywhere that Solaire is actually the firstborn son of Lord Gwyn, chief deity of Dark Souls.

Solaire’s incredible prowess is at conspicuous odds with the fact that his equipment is decidedly normal - rather like the Mario manual, this is a fact you’ll only discover if you take the time to read his gear’s description in your inventory. Solaire’s secret is hinted throughout, but there’s nothing so explicit or vulgar as a cutscene. You piece it together as you play. A hidden statue of a mother and child has the infant holding Solaire’s sword; elsewhere, the monument to Lord Gwyn’s firstborn has been removed. You learn about him by paying attention to what’s missing - or you don’t, crucially, but the adventure plays out the same - and this combination of meaning and interactivity is something only games can provide.

Something even more elegant lies beneath all that buried detail: Dark Souls crafts story from the raw emotions of your reactions to its various extraordinary environments. Take Sen’s Fortress. The entrance is an imposing metal maw which intrigues and intimidates. When you finally open the door, the area is immediately and relentlessly brutal: swinging blades, hidden traps and vicious, unfamiliar snake-men. After all that gloom and torment, your reward is Anor Londo: a crisp, elegant city, steeped in pale sunlight. (Except that it’s not really a reward, because Anor Londo has giants and Ornstein and Smough and dickhead Silver Knights with greatbows. But hey! At least it’s sunny.) Dark Souls never tells you how to feel, because it doesn’t need to. It trusts in the pacing of its journey, and your direct experience of it.

It’s even audacious enough to make this a shared experience. Where The Order preaches a single-player ideal it can’t deliver, Dark Souls is proudly communal. Soapstone messages left throughout the world are a more than just multiplayer device; they’re a reminder that no matter how bad it gets, others have tried before you and succeeded. A more upsetting example can be found in the Depths. The basilisks there can curse you, turning you to stone and killing you instantly. It makes this section uncommonly terrifying - nobody wants to be trapped for eternity in the cesspool pipe of the damned - and it provides a snapshot of somebody else's failure: the statues in the Depths are all other players who've been cursed.

That leads us neatly back to my opening point, since they’re a bit like the bricks in Super Mario Bros. Or are they? Well yes, because the reality of their condition fills us with similar nameless dread (and it really is nameless, since the fear of being turned to stone apparently doesn’t deserve a cool classification) but also no. When I see those statues, preserved not in amber, but shit, despair and panic, I think of my own story: crawling back to the Undead Merchant with half-health, grinding souls to buy a cure, going back to the Depths and getting cursed again. (I also think, ‘I’m glad I’m not that poor bastard’, then laugh like a prick.) Here, playing and feeling are indivisible, and this is surely the triumph of Dark Souls; it’s so good at folding mechanics into mythos that even the suffering of others can become part of your adventure, and in doing so, affect its future path.

Ahead of GTA 6, Take-Two CEO says he’s “not worried about AI creating hits” because it’s built on recycled data: “Big hits […] need to be created out of thin air”

Assassin's Creed Shadows devs "actively looking at" an even harder difficulty mode for the RPG: "How challenging do you want it?"