We may well be at peak epic fantasy. In a post Game Of Thrones world there are more George RR Martin imitators that you can shake a bloody sword at. But where are the innovators, the authors pushing epic fantasy forward into fresh territory?

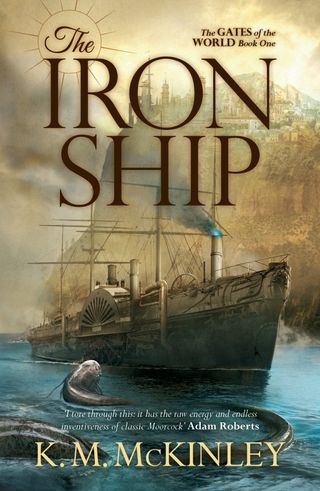

KM McKinley wants to show what epic fantasy is really capable of. Debut novel The Iron Ship sets out to explore lands far removed from the medieval-style setting that has become the fantasy standard.

Set on a world where gods roam grimy streets, the tides of the sea swamp continents and magic collides with science on every corner, The Iron Ship is about what happens when swords and sorcery meet industry and modernity.

We spoke to McKinley to find out all about the inspiration behind the novel and its key protagonists the Kressind siblings, as they make their way across an unconventional fantasy land...

SFX: What was the genesis of the novel?

KM McKinley: I began daydreaming about a high fantasy world that was well into the first phase of industrialisation whose underlying driver was the rational exploitation of magic. In our own world, early scientists were also mystics. What if the magic turned out to work and became the underpinning for the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution? That's what has happened in The Iron Ship.

To steal a phrase from George RR Martin, are you more of an architect or a gardener when it comes to constructing your novels – are you an advance planner or a make-it-up-as-you-go-along type?

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

KMM: I've done both cast-iron plans and blank-page adventuring. Generally I have an idea of what I want to write and the themes I want to explore, but do not meticulously plan. I'm too lazy, to be honest!

How would you describe the world of The Iron Ship, and how did you go about putting together a setting like this, and keep track of it all?

KMM: It’s a living, realistic, whole cloth world. I think a lot before I go to sleep and when I'm in the shower. Once the story reaches a critical mass, I'll start jotting down scenes and character arcs and later bits of dialogue. Finally, I'll rough out the plot. Most of the process takes place in my head though.

What was the inspiration for the twin planets?

KMM: I read a book about a fantasy planet orbiting a gas giant. There was no mention of how this astronomical set up would effect the planet. I began to consider how it would be to live on a planet subject to the immense tidal forces of a sister world. I'm also playing with the fantasy theme of circularity. The orbits of the planets – and the depiction of them in miniature in the Hag's machine – represent that.

How much world building did you do ahead of writing, and how much evolved on the page?

KMM: About 50/50. The main ideas came before the writing, how they work together came out of the writing process. The idea a story "writes itself" is an illusion, but you genuinely do get a sense of reality to writing that can feel transcendent sometimes. So I'll say, once a world or character reaches a level of complexity, it has the appearance of taking care of itself.

The plot follows the various siblings of the Kressind family – what was the inspiration for this brood of brothers (and their single sister), and how did you juggle so many story threads?

KMM: I come from a big family. Large families are increasingly unusual, but fascinating. I made a decision here to "write what you know". Family is very important to me. There are a lot of characters in the book because that's how life is. Even if you live in a small village in the middle of nowhere, you'll come across hundreds of people in your life. All of them affect your life somehow, as do millions upon millions of people you'll never even know existed. Juggling the plots was hard work, and perhaps it doesn't always work, but I think it helps build that idea of a "real" world.

One of the brothers, Guis, suffers from a form of mental illness with very real consequences. What was the inspiration for this?

KMM: I suffered from severe obsessive compulsive disorder for twenty or so years. I'm mostly over it now, but Guis's experience is based on my own, only his reality is one where magic is wielded through acts of will, and therefore his condition is actively dangerous.

The key magical race in The Iron Ship is the Tyn. What was the origin of the Tyn?

KMM: In our pre-scientific folkloric past, people believed in fairies and spirits of all kinds. Obviously, fairies don't exist here, but magic works in The Iron Ship... The fairy inspiration is why the Tyn are all shapes and sizes, but regard themselves as being one thing. Let me stress, they're not actually fairies, but something else. Their origin and nature will feature in later books.

Why did you choose to avoid conventional fantasy races?

KMM: Tolkien plundered Germanic mythology to brilliant effect to construct his legendarium. Pretty much everything else using the same tropes is a copy of a copy, although there are writers who play very well with what have become the archetypal fantasy races. Other writers use the same source material with different, excellent results. I wanted to create something unique (understanding, of course, that there is nothing new under the sun). Writing about dwarves, elves and orcs leads to an instant comparison to JRR Tolkien, and I'd come off worse.

There is a lot of magic in The Iron Ship, from necromancy to the glimmer that powers so much of the new technology. What were the challenges in building a magic system that logically works, while retaining a sense of wonder?

KMM: Magic is really important to this story! Far more important than it might first appear. I can definitively state there is only one kind of magic in The Iron Ship despite its diverse applications, and that the magic system does have a logical basis. Its nature is fundamental to the nature of the world. I suppose I'm attempting to retain a sense of wonder by not explaining it right from the get go. We'll see how that works!

The gods of The Iron Ship have fallen from grace, and one of them can be found propping up the bar in his local pub – the gods are real, but diminished. It’s an unusual presentation of deities – how did settle upon it?

KMM: I don't think it gives much away to say the gods' existence is also linked to the magic and to the world's history. In ancient Greece and Rome the gods were regarded as troublesome. My thinking was, what if they got to be such a bother someone kicked them out?

There’s an industrial revolution going on in the novel and the world is changing. Why was it so important to address these seismic societal shifts, and what makes change such an appealing theme to you?

KMM: Fantasy is predicated on the seeming of change, but it's not real change - great effort is expended to get back to the good old days. In our reality, we're living through the latest and greatest of several technological singularities that have utterly altered our world. To my aging eyes, our world is becoming increasingly fantastical. We're living science fiction. I wanted a fantasy world that mirrored that, one with deep and mysterious roots but is off balance, rushing headlong toward change, with all the adventure, opportunity and problems that brings.

How long do you anticipate The Gates Of The World will be when it’s finished? A trilogy? Longer?

KMM: It's supposed to be three books. It'll almost certainly be longer, but I promise I won't let it get out of hand!

The Iron Ship is out now.

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.