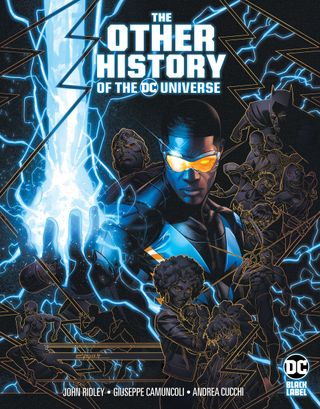

John Ridley gives a diverse and honest look at DC in The Other History of the DC Universe

The writer of 12 Yeas a Slave grapples with DC history and provides a new point of view in The Other History of the DC Universe

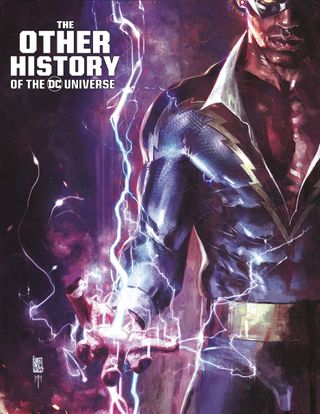

The history of the DC Universe has been unfolding for over 80 years, and John Ridley has been reading it as a fan of it for decades. But he's also a writer - an Academy Award-winning screenwriter, at that - and he has his own ideas about what happened that wasn't on the page at the time at DC. Hence his new series The Other History of DC Universe.

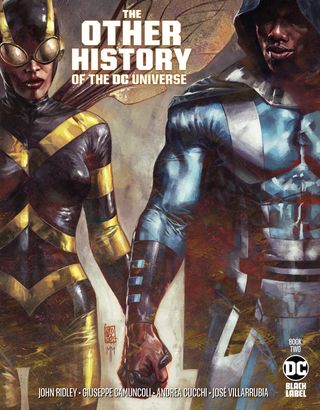

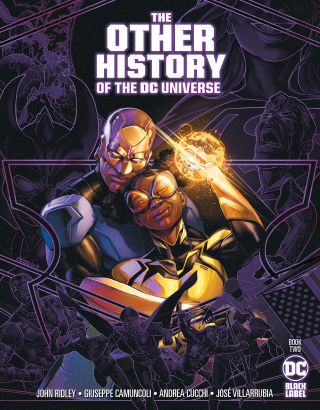

Launching this week, this five-issue prestige format series teams Ridley with artists Giuseppe Camuncoli, Andrea Cucchi, and Jose Villarrubia to explore the mythology of the DCU and offer a different, more diverse, perspective on the major events in DC superhero history.

Newsarama took part in a roundtable interview with John Ridley and other press outlets, going into detail about his childhood (and adult) fandom for Black Lightning, his decision to return to comic books, and the thoughts and emotions behind this new take on DC continuity.

John, from what I've read of The Other History of DC Universe #1 it looks like this is a pretty sweeping take on DC history.

Were there any particular events or moments that cried out for reevaluation? Did you look at something like Final Night and say 'Oh, that may have been how it went down, but that's not how folks would have seen it'?

John Ridley: It's a pretty exhaustive look at the DC universe. Obviously, we're talking about a storytelling arc, a narrative arc in the history of DC, National Periodicals, and all that going back more than 80 years. It's certainly not an 80-year dive, but what I believe you can tell from the first issue - we do want to set this up as though it were a real timeline that these were real mortal people that their combined histories are going to run from about early '70s with Jefferson Pierce as a younger person through the mid-'00s with Anissa Pierce and her dealing with her life and her career as a hero.

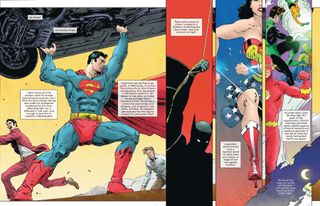

In terms of how I chose to look at certain events... I believe in the first issue, Supergirl's arrival, there are other events – Supergirl's death, the death of Superman; very large scale events in the history of the DC universe - Wonder Woman killing Maxwell Lord, things like that. But what was more important to me rather than just drop these events into history and say 'Oh, this happened,' but really try to examine them from the perspectives of these characters.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

So, some of these events, we may see more than once and the characters comment on them. Some of the views of the characters represent different views of the same similar moments in history. So, it was less to me about just putting in obelisks on a timeline and saying this happened, but more importantly, how do these events - how are they contextualized? How are they absorbed? How is the meaning expressed to the lead characters in each one of these stories?

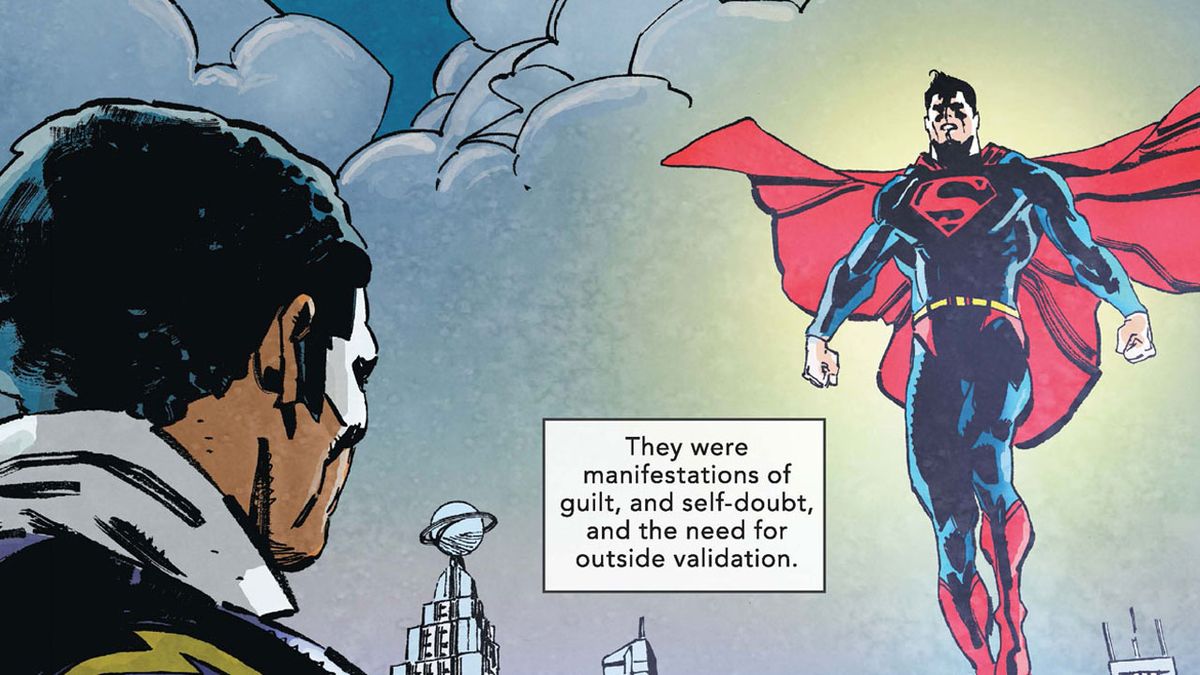

Less about just revisiting a big event and saying 'Remember when Superman died? Great, let's move on.' But more about other characters saying, 'Wow, I'd always thought this about Superman, but when we lost him, I had to re-examine how I felt or what it meant to the larger universe.' If the universe was real, what happens when we lose a really remarkable individual, maybe had a troubled past, maybe we felt differently about them, but that loss - how do we collectively feel about it in that moment?

What was the decision behind making this part of the Black Label instead of DC's regular line?

Ridley: When we started this, almost three years ago now the Black Label was new. I'll be honest, I'm only half-joking, when we sat down and talked about the Other History of the DC Universe, and at the time it was Jim Lee and Dan DiDio and they said 'We really liked this idea. We want to find the right format for it,' and they came back and they said we got this thing - Black Label. And I was like, 'Oh wow, they're giving me my own label. It's for a black guy.' Then they explained it's just premium black - best that it can be.

This was one of the first series that was announced for Black Label. I think it's really a terrific space for it. I love the concept of what DC is doing with these very premium books that are certainly there for people who love graphic novels, love comic books, but are also targeted towards a wider audience. An audience that may not normally go to their comic book shop on a regular basis.

But this was a concept and format that both arrived simultaneously. Obviously, this is coming out a lot later now that DC has had an opportunity to work with Black Label. It was like Reese's peanut butter cups. It was chocolate and peanut butter. If you're old enough to remember the old commercials, people tripped into each other and said, 'Oh this is a great thing.' It was more of an accidental arrival to this than a sharply planned, this kind of story can only work in this format.

You obviously came into this as a Black Lightning fan. In researching and then writing this series, did anything jump out and surprise you even with your long personal history with the character in mind?

Ridley: At least how I interpreted it, even if you read some of the later Outsiders stories, when Annissa is a member of the Outsiders – he was a tough guy. I don't mean just tough that he can take a punch, but he really to me reflected black men of a certain age that I knew. Certainly, people like my dad who is in my opinion is the greatest Dad anyone would want.

With what my dad has accomplished in his life, I'll spend the rest of my life chasing, but he was a man of his era when life wasn't easy. Black, white, or other - life wasn't easy. If you were a black man, life was really not easy. There were struggles. There were setbacks. There were accomplishments that people of his age just did because that was the way life was.

For me, looking back on these Black Lightning stories, as much as I enjoyed them, I really began to see more of a reflection of men that I knew. So, there was a desire for me within that storytelling to go back and put context to why Jefferson was a little bit more intractable in some of his beliefs. His worldview was a little less malleable than maybe some other characters, but then ultimately make sure that in places you saw him become aware of that.

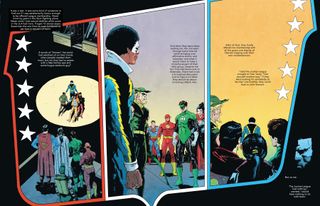

Certainly, his relationship with John Stewart, which is a moment I just love as a person. Two black men, two men, and saying it's okay with these characters that they can have a moment that they can cry, that they can be out of uniform and literally hug it out.

And how do you arrive at that in storytelling? There's yet more of that with Anissa in part five, where there are things he has to acknowledge with his daughter about how he raised her about choices he made - some unconscious choices, some unconscious bias.

With all of these characters, your question was about Black Lightning, but what I love with all of these characters again, was really excavating that humanity. In all of the comic universe, there's somebody who can run fast, somebody who's bendable, and somebody who can make heat beams come out of their eyes; but what makes these characters indelible are their own stories and the artists and artisans in the history of comic books who've made these characters very particular.

For me, when I started going back into these stories and I saw particular natures, I wanted to lean into that, I really wanted to explain that, and then I wanted to reconcile that and show that you can be particular, but you can still have emotions. Particularly black men, we don't get to see that enough - black men just being human, being people, and having emotions - positive emotions: love, crying, and empathy. Crying isn't an emotion. It's an action, but you know.

What do you feel is the most misunderstood part of DC's take on superheroes, and is there one particular element that you wanted to address in this very first issue?

Ridley: I would say maybe not misunderstood, but if people separate universes, one of the things I think people talk about particularly now is that DC is an amazing universe - it's a fictional universe. It really is fictional, it's fiction on top of fiction, it's Metropolis, it's Gotham. It's these places that aren't quite real and therefore it's this extra bit of separation from the audience.

One of the things that I really wanted to do was to try to marry the Other History of the DC Universe with real history, as much as possible. Whether that's additional locations, Jefferson in the first issue talks about spending time in Milwaukee, talks about being in real places, certainly real moments in history from the Munich massacre to the Iran hostage situation. Where, hopefully, if we've all done our jobs correctly, it feels like you can track these characters through a real history and what it was like to be an individual with extraordinary abilities and be faced with challenges that are not just portals opening in the sky and aliens dropping in, but real challenges.

That powers alone are not always enough to combat the challenges that people face in the world. If the primary word in that question is 'misconception,' I don't know if this answer is correct, but if I'm going to look at concepts that people may ascribe to the DC universe as a negative to me - I'm not saying it's a negative, but it was certainly something I wanted to try to juxtapose against reality or realities to try to hopefully make this series of books feel as seeped in reality as possible. I wanted to do that with everything, with these characters, it's much more about them as characters. Jefferson Pierce, Mal, Karen, Tatsu Yamashiro, Renee, Anissa - not Black Lightning, not Katana, and not the Thunder. Certainly, they're represented as those characters in these stories wanting to try to make these stories feel as real as humanly possible.

You've worked on a few stories for DC in the past, but what made you want to return to the company for The Other History of DC Universe and your other upcoming projects?

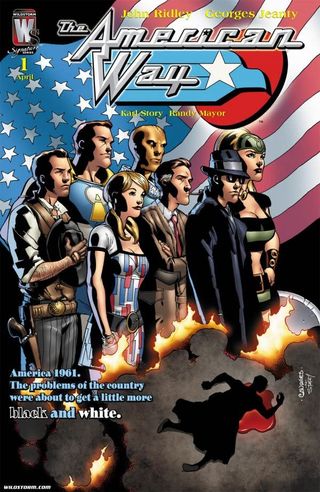

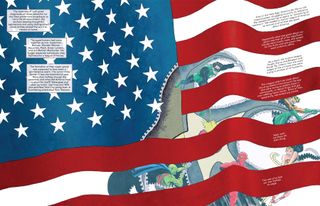

Ridley: It was odd. Certainly, I was very blessed to have written some stories in the past. They were kind of one-offs or they were these odd little stories and they were fun. I really loved doing them, especially the American Way. In all the things that I've done, in all different mediums, The American Way is probably one of my all-time favorite projects. Certainly, one that personally means the most to me.

DC was very gracious in approaching me about doing another series of the American Way. It wasn't like I was thinking, 'Let me get back into comic book writing', but they offered me a blind deal for another project. And that was a real show of faith on their part that they thought that I could not only write graphic novels or comic books, but write them outside their very specific book that only appeared twice in 10 years. It's like a comet orbiting the solar system.

When they asked me to sit down and really think about what I wanted to do and why I wanted to do it - that's what I wanted to do. The mythology of DC has meant so much to me as a kid growing up, as a creator, as somebody who just loves entertainment, and the concept of saying can I be really honorific to all of the stories that I grew up reading, to the men and women who've done all this work. Can I be honorific to the past? Can I create a story that is urgent for the moment? Something that hopefully then endures the test of time. To me, the Other History of the DC Universe was that perfect project.

It really encapsulated everything that the DC universe meant to me. And then in terms of going forward, it was just people at DC started reaching out and saying, 'Do you want to do Batman?' And you know what, it's like somebody reaching out, 'Do you want to be the president?' 'Do you want to be king?' That's a very special piece of real estate. I'm going to take it on and was able to take it on with [Batman group editor] Ben Abernathy, who was the guy who originally brought me into comic books. So, it was really not only special to work with a great group editor, but with somebody that I had a really close personal history with.

You've mentioned before that you sought outside perspectives when it came to working on characters like Renee Montoya. With those outside perspectives in mind, what do you feel you brought personally to those characters who don't share your background?

Ridley: Well, honestly, I hope and believe as with all these characters I bring my absolute best work. On the one hand, you never want to, whether it's intentionally or unintentionally, write something that's just - particularly in the world we live in, it's just patently offensive. Even if you're careful - people are going to love it. They're going to hate it. Even if you're writing something where you're being very careful and being very responsible more than just great, we wrote this. We didn't offend anybody. We want to inspire people. The reality is that when you create something, there is an implicit invitation for other people to join in with their time, to join in with their money. But hopefully more than anything that at some point they'll join with their talent.

Back in the day, Tony Isabella, a white man wrote Black Lightning. I don't know why. I don't know if he wrote it because he looked at the landscape and said they're not enough characters of color. I don't know if he wrote it because DC said, 'We'll pay you a couple of extra bucks', but Tony did this. And he had no idea that he was speaking to an eight-year-old kid back in the day saying 'You can do this.' And Tony did the best he could, and I mean that sincerely.

Anybody can look at that work, particularly anything written in the '70s and go, 'You know, should have been more of this or that.' All I know is one of the reasons that I'm here, one of the reasons I'm doing any entertainment at all is because of guys like him – who said if you enjoy this, why shouldn't you be part of this?

What I hope more than anything than that exploration and going to other people and saying check my work and check it honestly, that beyond doing everything we can to not be offensive, that the most important thing we do is that we're being inspirational to anyone and everyone to say come and be part of this in any way you choose.

What character did you really want to include as a perspective character, but just couldn't find the space for?

Ridley: You can almost pick any character of color, almost any female character, an LGBTQ community character. I could not find a Muslim character. I really think that that would have been very important to include in the work. I mean look it's five issues. We have our lead characters. We have other characters that we blend in. But it's never enough. I hope it was representational. I certainly didn't want to go, here's one from column A, one from column B. I wanted characters whose history I was familiar with, characters whose histories spoke to me.

It wasn't just me blindly going let me try to interpret this character as a character. I feel a closeness to the overall history, but any character who's not in here, any group that's not represented, is a group that I wish that had been represented. Hopefully, if the series does well, DC will go to other creators and say there are still yet more Other History stories to be told.

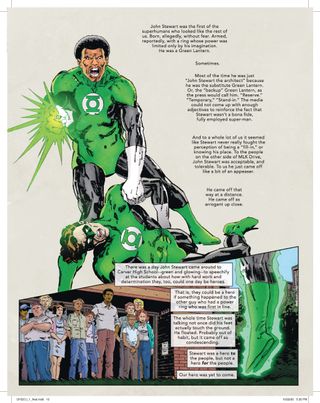

Can you talk about the similarities and differences between John Stewart and Black Lightning? I really enjoyed Jefferson's change of heart when it came to what he initially believed about John Stewart, and how their talk changed his mind.

Ridley: One of the differences that I wanted to try to point out, at least from Jefferson's perspective is there was a level with all the Green Lanterns. You're chosen. Who's the person without fear? Who's the best person to watch over this space sector? Even if you, as John Stewart was, was the backup Green Lantern. He was one of the best of the best if somebody else the hand of God shows you, and Jefferson was this young man, everything in his life felt like a struggle. The loss of his father. I couldn't be there. I wanted to be the greatest athlete, but that moment was interrupted by one of the greatest horrors.

He goes through life, 'Yeah, I have a metal. What does that mean? I'm going to make myself into a teacher. I'm going to work so hard to make my students the best.' In my interpretation of that story, you have John Stewart, as an architect, very middle-class, chosen to be the best. And he feels like this anointed black man and Jefferson looks at this, and he has a problem with folks who feel anointed. Whether it's John Stewart, whether it's Superman - it's like 'You have to work, man. I had to work.' I being Jefferson Pierce. 'I've had to work for everything. Life hasn't been easy. You have to hit the books. You have to hit life. You have to hit hard.' He's talking about one of his students like that. That's where that friction is.

Then there's that moment, as you referenced, later in the book where they talk about that and John really talks about being the first is not easy, carrying that around, those expectations - the expectations that these two men put on each other.

One of the things that was really important to me in all of this series, I think it would have been so easy to write five books where it's a black man, a young black couple, Latinx, or an Asian individual just railing against the prevailing culture. It sucks. It's difficult. It marginalizes. It doesn't see us. That could have been five books, but sometimes the biggest struggles that we face. And I'll just say this for me as a black man, it's not always with the prevailing culture, that it expects so little of us. Sometimes that's the easiest fight.

We know you don't like us. You don't expect anything. Doesn't matter. We're going to excel. We're going to do it. Sometimes the most difficult thing is how we view each other and those expectations. How we represent the race, how we represent our groups? Are we doing enough? Are you saying too much? Do you represent me? And that's what I really wanted to get in these books is more of these personal struggles of identity. A perspective of how these characters see themselves of the expectations they put on themselves. You see that certainly in that first issue.

It was much more about this narrative arc of Jefferson Pierce and John Stewart arriving to that moment, which to me is a really beautiful moment. It allows Jefferson, at least in this issue, to complete his story. He's got some more completion to go with the Anissa later, but it's a moment at the end of this book where he says 'I don't need to be Black Lightning. I don't need to be that kind of a hero. But by the way, let me take my costume just in case.' I am that guy. We finally reached Jefferson and Black Lightning - they are one at that point of the story.

Giuseppe Camuncoli is drawing these five issues. How has it been working with him?

Ridley: He's been the only artist on the entire series. He was brought in early and his work is so phenomenally instrumental to everything that's happening.

First of all, it's great. But when I came into this book, I didn't want a book that was just straight up sequential art. It's nothing against sequential art. We always knew it was going to be a more prestige format that became Black Label. We wanted it to feel like something that was more than a regular comic book. We talked about just having spot art - prose and just one piece of art. Then that felt a little limiting.

When Camuncoli came on board, he did the layout – it was, to take these pages of prose, which originally the mandate was trying to keep every book close to 30 something pages, but it was a lot of prose. It was already like 30 pages of prose and then Camuncoli would do these layouts and come back and go 'You have this prose, but it would be a little better if it was like this.' And I was like 'Fine.'

Then DC would take a 30-page book, and all of a sudden it was a 45-page book, and DC to their credit was like, 'Okay, they'll read it and go this is great.' So, this one's going to be 45 pages, but Camuncoli was so instrumental because he would take the prose, lay it out, we get the layouts back. I would change the prose, get it back to him. We would take it to lettering, then that was a whole other thing just how was the lettering going to lay?

That was something we didn't really think about until the artwork came back because wanted it different. It's not bubbles. It's all internal dialogue. But is it captioned boxes? Is it text on image? If it is text on image, what does that color need to be? This was an ever-evolving project.

There's a real reason why this has taken three years. And, honestly, we're not done. We're not scrambling, but we got this issue done on time. We will get them all done on time, but we're still putting on the ink, trying to get the ink to dry with these. But this book wouldn't exist without Camuncoli, period.

There's a great moment early in Black Lightning's career where he addresses Superman's privilege to his face, though Lightning's feelings on Superman definitely evolve over time. Why was that moment important to you to include and did it change much from your original draft?

Ridley: It didn't change much from my original draft. I remember that moment when I was a kid, I feel differently about it now as an adult, but to have a moment like that - it was a real honest, true moment. If you go back and you read those comic books they read on a certain level of entertainment. But there is this thing about the way Black Lightning is viewed as a vigilante, and yes, Batman was viewed as a vigilante early on, but in this timeline their costume vigilantes around. Why is Black Lightning such a problem? Why does the police, why do they view him that way? Why in the history of storytelling is this probably the first time that we see Superman in Suicide Slums.

Some people may say, 'Well, Suicide Slum didn't exist.' If we're going to treat these as real stories. Well then yes, it did. Why is Superman in here? And what would a person of color say if you're coming to do something here, 'I got an array of things we can do, but just show up with your superpowers now, because of something that was in the media and you feel like you need to problem-solve.' 'We got problems. I'd love for you to come. I'm here to work on those problems, but this is the first time you showed up.'

That was important for me to include because for me that is a real emotion. And again, in every aspect, I want this book to feel real, but I also do want to show the evolution of these characters. That's the most important thing - if these characters, any of them just remain flat and dogmatic page to page. I'm not going to say that doesn't happen in real life. They're plenty of people - cradle-to-grave, they're kind of hyper consistent to the point that they don't evolve as humans, but you want to see these evolutions.

Let me put it this way as a storyteller, I want to see these evolutions because I want these characters to evolve. I want them to arrive to a place where their blind spots are set aside. Easy to put on a costume, easy to say that you're a hero. Being a hero is something to me, a little bit more fundamental, and that's being able to see yourself in others.

This is one of two high-profile DC projects you've got coming soon, the other being your Future State: Next Batman series. How do the thematic concerns of that project differ from this one?

Ridley: The thematic concerns of the other one is that it really needed to fit into what's going on in Gotham - in the Bat universe now. And, yes, this is 'Future State, 'so all of these comics, they're jumping ahead a little bit, but there's a real plan. There are certainly things that I can't give away and can't talk about.

This was taking meetings with other writers, with the group editor, sitting down and having a tighter set of guard rails, and saying within these guard rails, within the sandbox, you can do this. But it's like when you were a kid and your parents take you to the park and they say you can go on the slide and you can go on the seesaw, but don't leave this area. Don't go away, have all the fun you can, but I'm going to sit right here. I'm watching you. Don't go here. Don't go there.

So that was a much bigger part with the Next Batman of saying it needs to include these characters. This character is going to be the new commissioner, the new mayor. Their attitude about what's going on is this, and it needs to be reflected in your book. It was great fun. It was a great challenge. I hope that there is, without giving anything away, perhaps there'll be some more. But there was more of working with a much larger team having defined boundaries and then having as much fun as humanly possible within those boundaries.

In your opinion, what made Vixen the right choice to show Black Lightning that a Black superhero could be accepted by not just society, but also the Justice League?

Ridley: In real-life history, Vixen was going to come out as a character, and I believe have her own run. There was, I forget what it's called, like the great comic implosion or whatever, but there was just this streamlining of comics - Vixen went away.

But then the next time we see her, she's working with Superman or appearing in a Superman comic, which is a pretty big deal. Vixen is a character who was going to be in this, the concept of taking what really happened in history where a character was about to break and then went away. Then for some reason shows up again. I thought it would be interesting for Jefferson Pierce, again talking about his blind spots is this guy with this chip on the shoulder saying, hey lady, the heroes don't have any use for people like us.

You seem really talented. It's not worth your while. And then all of a sudden, bam, she's out there and she's doing what she does. I just thought all the way around from real history to Jefferson's myopic view to a woman of color, who's getting it done. Who's shown up working with Superman. I just thought that was great.

It was very important for me to, again, not just show these heroes as being heroic and always making the right decisions, but that Jefferson is fallible. It's not just him fighting the prevailing culture, it's him not seeing that Mari is not only capable, but she's more capable than he is. Whether her capability is her abilities, whether her capabilities is her maybe a little bit more malleability or even a lack of malleability that she knows she can be who she is working with some of the other greatest heroes.

Everything about that really spoke to this narrative. I will say that was one of the really enjoyable things about the overall process with the Other History of the DC Universe was taking moments and saying, 'Okay, how do I, John Ridley, how am I going to contextualize or maybe even slightly recontextualized these moments?'

If I couldn't do an entire series featuring Mari, I was not going to not include her. And I was not going to make sure that she did not have a bit of an arc within this story, and that arc was going to be impactful. Not just she shows up, but even in her dual appearances, there was going to be some specificity of storytelling, some specificity in terms of what happened with her two appearances. A quick answer to your question, it wasn't that I necessarily thought it was right. I thought that everything that was in there created and supposed was already absolutely correct with the story that I wanted to tell.

We often see the Justice League as a team of altruistic heroes coming together for the greater good, but we see a lot of their faults here too, at times making them feel more like Congress than a superhero team and all the pitfalls that label carries. If you could make one fundamental change to the Justice League and how they operate, what would it be and why?

Ridley: The fact that you make it sound like Congress, that's like hyper depressing, they'll never get anything done. You pose a really interesting question. And how, if the Justice League were real, How would you make them better? How would you make them more responsive?

I don't know that I have a good answer to that. I think ultimately if I thought of them as a real super team, I think there are some things that are the obvious emergencies that they're going to respond to, aliens from outer space.

No two ways about it, but when it comes to things that are a little bit more political. How are they going to feel about it? What would they really do? And I do think that historically creators have put that into the storytelling at certain times. You see that with the formation of the Outsiders where Batman is like 'You guys are too worried about borders and things like that.'

This may not be straight with the Justice League, but when Wonder Woman did kill Max Lord and she's like, 'I got to do what I got to do. I'm a warrior and I'm going to do it.' People freaked out about that, and that's something that we do talk about in this series. Did they freak out because Wonder Woman did it, or did they freak out because a woman killed a man on live TV? There are other male heroes killing male heroes.

I don't know that I have a good answer to your question. What would I do to make the Justice League more responsive? Sometimes as we see in democracies, democracy is great, but the more that voices are added, the harder it is sometimes to get things done. If the Justice League were autocratic. If they were in some ways like the Authority - that's an interesting story. The Authority stories were always great, but that's a whole other kind of super-team where it's like we're going to fix the world whether you like it or not. So, I don't know what could be done, what should be done - to marry the fun storytelling with the challenges of real life.

As a prolific screenwriter, what do you enjoy about the comic book medium? What makes the process similar and different?

Ridley: You know what I enjoy about writing comic books - getting to the last page. It's so hard writing comic books. No disrespect to my peers who are writing TV or movies right now. I continue to do that. But writing comic books is so freaking hard. I mean, think about it, everything is about efficiencies. How many words can you really get into a bubble? How many bubbles are going to go onto a panel? Every bubble is going to block some of the amazing art. How many panels per page?

Max, maybe there are usually 22 pages per issue. That's not a lot of real estate. Then you're working with a history that people love. Comic book fans are the most passionate fans that are out there. So, you want to be respectful. You want to be honorific, you want to do your own thing, but you also want to make sure that you're doing something that people are going to want to revisit next week and follow these characters. So, it's hard.

I enjoy working with the artists. I really enjoy working with the editors. They've been amazing and I've enjoyed revisiting these characters. I've enjoyed the Next Batman trying to set up a slightly different Gotham City. There's a lot of enjoyment there, I can't lie it's really tough.

Particularly, when you basically have written one graphic novel series every 10 years, and then you kind of write one that takes three years, and then somebody says we need that issue. You finished with your story meeting and somebody says, great, can you have that in a week? And you're like, oh yeah, sure. I can do that. It's great. It's really rewarding, but it's really hard.

What can you tease about the perspectives and concerns of issue #2 and how they differ from issue #1?

Ridley: The big change in perspective is that you have a couple, Mal and Karen, sharing the same story. In the first issue (and some of the subsequent issues), it's one person with their view of history. What I thought was kind of fun, or at least it was very fun for me was - it's kind of like the Newlywed Game, that whole issue. You have a couple that's sitting down together telling their shared story. And one of them is like, wait 'No, that's not the way it was. It was like this.'

And I did want the second issue also to be a little lighter than the first issue. Trust me, I knew coming out of that first issue, even though I think there are moments in it where you see Jefferson Pierce finding a greater level of humanity within himself. It's a tough way to start from the Munich massacre all the way to John Stewart accidentally blowing up a planet - whether it's real or imagined, that's some tough stuff.

In issue 2, while there's still some tough storytelling, some very tough things from the seventies - Teen Titans back in the day, their stories were really progressive. If you have not gone back and looked at some of those stories, they're hyper progressive, so there's tough stuff that's going on, but I did want it to be a little lighter. I did want it to be about a young black couple who are in love, committed to each other, and figure it out and find a way.

It's a dual perspective. It's a lighter perspective. It's a couple's perspective. It's teens' perspective about hyper otherization. Beyond just being black or female, teens are always trying to find themselves. They're always trying to figure out how do I fit in. There's stuff about bullying even within the Teen Titans - they don't realize how they're talking to each other and based on real things that were said in some of these books. So, the perspective is a bit lighter, a little bit more fun, but definitely leaning into young people trying to figure out who they are in the world.

Are there other DC characters you'd like to explore for the Other History of DC Universe series? Would you like to write a sequel?

Ridley: It's like the end of a boxing match and the boxers have just gone the distance, and it was a close, tough fight. And the announcer or the ring reporter asks, 'Do you want a rematch?' - the boxer is like 'I can't even think about that right now? I'm so beat up. I can't think about it.'

This series will probably genuinely, I know I said this about The American Way, but this is one of the most rewarding things I've ever done. One of the most special things that I've ever done. It's one of the most exhausting things. I mean three years of really constant work, research, and back and forth. I hope the series does well because of the faith that DC put into it. I hope the series does well because of all the hard work that so many people put into it. I hope the series does well because I just think it's hugely entertaining.

I think it's wonderful to visit these characters, and really get their origins, really get their history, really see these moments. But I honestly, I cannot think about what it would be like to do a follow-up to this at this moment, and I'm certainly not precious about it. Like, 'Oh, if I don't do it, nobody should.'

If DC said, 'We're doing five more, and he, she, or they are going to be the lead creator on it,' I'd be like, 'That's great. We've become a brand.' That would make me perhaps even happier to know that I contributed to a brand, but for me personally I can't even think about approaching this again right now. Ask me in six, eight months, or a year, but right now I seriously can't even think about it.

Kat has been working in the comic book industry as a critic for over a decade with her YouTube channel, Comic Uno. She’s been writing for Newsarama since 2017 and also currently writes for DC Comics’ DC Universe - bylines include IGN, Fandom, and TV Guide. She writes her own comics with her titles Like Father, Like Daughter and They Call Her…The Dancer. Calamia has a Bachelor’s degree in Communications and minor in Journalism through Marymount Manhattan and a MFA in Writing and Producing Television from LIU Brooklyn.