Jackass 3 is a beautiful snapshot of friendship

As Jackass 3 turns 10, we look back on the threequel that brought the once monumental franchise to an end

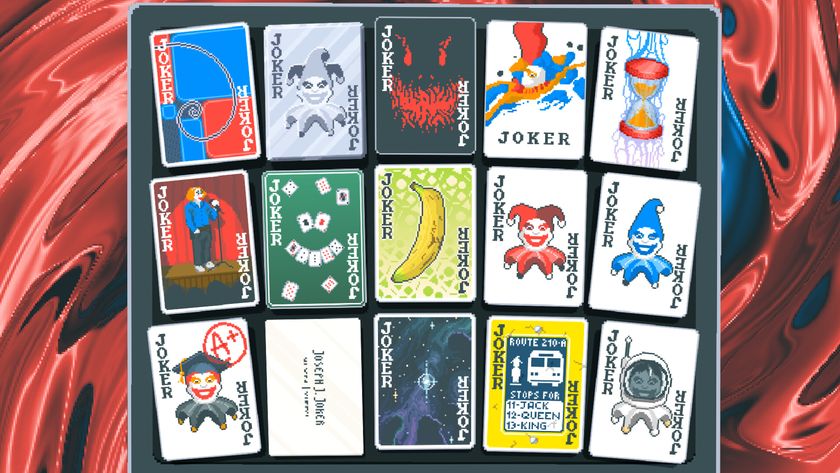

Ten years ago, the culture-dominating Jackass franchise ended with a bang: with the release of Jackass 3D, a glossy, high-production-value threequel that nearly doubled the budget of the second film and quadrupled that of the first. It’s clear from the start where the money has been spent: on high-definition cameras, gimmicky 3D tricks, a Beavis and Butthead feature, slow-motion stunts, explosive set pieces, and lots of costumes. But, despite the video quality, Jackass 3D doesn’t lose the spirit of its predecessors – instead, it functions as a picture-perfect sendoff.

Jackass was born in the year 2000, when friends Jeff Tremaine, Johnny Knoxville, and Spike Jonze put together a stunt show, assembling a team of misfits, skaters, and friends to do the most painful, gross, embarrassing things possible to themselves and one another. There is no overstating the cultural influence of Jackass throughout the 00s; in fact, those of us born in the '80s and '90s will remember just how many people landed themselves in the hospital trying to imitate stunts. Capitalising and building on the skate and slacker culture that had proliferated in the '90s, Jackass was simply about friends wasting time, and that’s what made it so special.

After airing for three wildly successful seasons on MTV between 2000-2002, Jackass: The Movie was released, in part out of necessity, with Johnny Knoxville, Steve-O, Bam Margera, Wee Man, and friends lamenting the restrictions that MTV placed on them. A film was the answer, and The Movie saw Jackass skyrocket, making almost $80 million on a $5 million budget. All of a sudden, Jackass had a tangible impact on the world outside of their niche audience of late-night viewers.

With the release of spinoffs like Wildboyz, Viva La Bam, and Dr. Steve O, as well as the sequel Jackass Number Two and a number of appearances on shows like Cribs, the Jackass crew were the faces of a certain subculture in the '00s. Naturally, other stunt shows and, later, YouTube channels tried to follow in its wake, but they failed.

Sure, the copycats might have done the grossest, most painful thing imaginable, and they might have even racked up millions of views doing it, but Jackass was unique. Not only in its pain factor, but in its authenticity and the bond between the men at its core. The Jackass crew rarely tried to truly hurt or upset each other, and the stunts were mostly consensual. When they weren’t, the stunts would always lead to these men laughing and helping one another up. Shows like Dirty Sanchez could copy the horror, but never the chemistry.

When Jackass began, it was a reflection of how suburban teenagers and young adults actually behaved; without phones or social media, they imitated what the Jackass guys did because they were doing some version that day anyway. By the time Jackass 3 was released, in 2010, we had iPhones, Gossip Girl and Twitter – all the markers of a busy modern culture that rarely leaves anyone with time to kill. The carefree hedonism of the '00s was waning, and the cast knew it, opting to retire their schtick with a bang rather than let it bleed out. They made the most of every second and every penny from the get-go, with the big-budget introduction seeing the gang stand against a rainbow backdrop as they get the shit beaten out of them in slo-mo. From there, the movie is pure Jackass: a 90-minute fever dream that feels more like an ever-escalating clip show of outtakes than a movie, featuring a cast of old friends like Tony Hawk and American Pie’s Seann William Scott.

Still, Jackass 3 feels anything but forced. The sheer joy that those men get from hurting one another reverberates through every punch, scream, and open-mouthed laugh. It would have been easy for them to sell out: to drag on the franchise, make more money, and push Jackass past its reasonable expiration date. Instead, and much to the ire of fans who just want more, they cut it off at its most successful point, leaving a meaningful legacy that captures just how much fun they truly had; electrocuting one another, pissing everywhere, smashing shit up. It was juvenile, sure, and it was agonising to watch. But it captured a pure friendship in a group of men that leaned into softness, never pretending to be any tougher than they were.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Post-2010, there’s little evidence that we ever had a slacker culture or even TV shows that were just 20 minutes of dudes doing meaningless stuff for a joke. The world is fast and it’s painful, and we all have to be engaged and aware at all times. It would also be remiss not to talk about Ryan Dunn, a key member of Jackass and a close friend of everyone involved, who died tragically in 2011, casting a dark shadow over the idea of revisiting the format, at least for a while. The Jackass guys had never shied away from confronting their long-lasting pain – even featuring doctors and x-rays in the movies – but the illusion of invincibility started to fade. Jackass 3 signalled the end of that seemingly consequence-free era, and it did so with all the grace and elegance of the entire franchise; that is to say, none. But it also did so with all of its authenticity, kindness, and truth.

Jackass 3 ends with a very literal bang; the room around them explodes and the set floods. Rip Taylor, a regular feature in '90s and '00s comedy, comes out to make his customary Jackass cameo. The gang – bruised, soaked, and covered in confetti – congratulate one another, laughing and hugging. The credits, which go on for ten minutes as friends, family, and collaborators are listed, are accompanied by a series of fitting songs: the TV show's theme, then CKY, leading into Karen O, a friend of Spike Jonze, singing a cover of Knoxville’s cousin Roger Alan Wade’s “If You’re Gonna Be dumb, You Gotta Be Tough” before Weezer close out with “Memories”. Stunts, outtakes, cameos, and childhood photographs of the cast and crew continue to play, and it’s a near-complete snapshot of the time that they not only epitomised but helped create, a time that it’s easy to be nostalgic for in an age of unrelenting information and chaos.

Towards the end of the credits, Tremaine asks Wee Man: “Is the shoot over?” Wee Man, dressed as a baby, looks at the camera and says, “Yeah. What did you want out of it? You got whatever,” then puts up his middle finger and walks away. That alone captures the spirit of Jackass: friendship, apathy, some light offence. What did you want out of Jackass? I wanted to escape and to laugh. We got so much more.

Marianne Eloise works as a freelance journalist covering film, TV, wellness, digital culture, money, and music, and a variety of other topics. You'll find her bylines in a variety of print and online publications, such as 12DOVE, The Cut, The New York Times, Vulture, i-D, and Dazed.