"I've been mugged myself..."

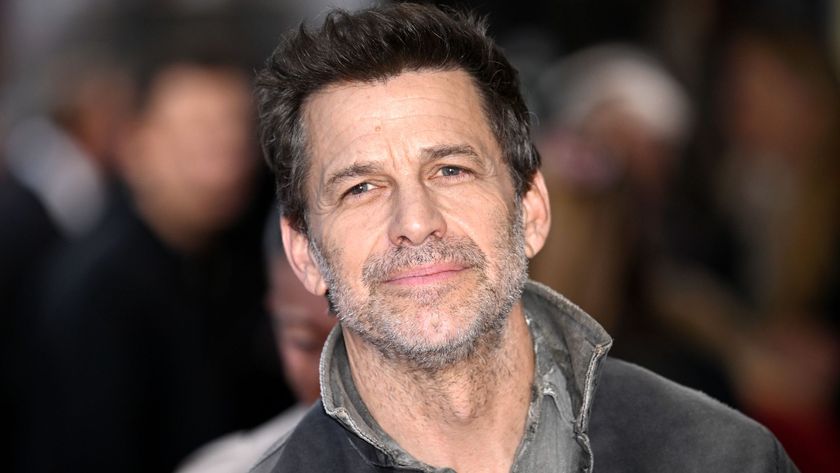

South African helmer Gavin Hood on shooting Tsotsi in the townships…

Total Film talks to the director of this year's Oscar-winning Best Foreign Language Film...

Tsotsi’s based on an Athol Fugard book. Were you worried about whether the great man would like it?

I was very nervous about what Athol would thnk; he was reluctant to be involved in any way because he feels his medium is the theatre and he didn’t want to be used as a sounding board. He read the script when it was done and said he liked it very much; and then when we finished the film we had a private screening for him in San Diego. When it was over I got this call: ‘Hello Gavin, it’s Athol. Bloody marvellous, mate!’ The next minute I was at his house having a wonderful chat with my hero. I know it sounds sentimental, but it was a moving experience to have him like it.

What logistical problems did you face shooting in the townships?

My location scout was looking at this township and he was carjacked; fortunately he wasn’t injured and he made his way back by foot. That kind of made us decide not to use that particular township! But I had worked in another area on educational dramas made to examine issues like HIV and teenage prostitution, so I knew the kids there, I knew the environment. The people were so cool; they wanted us to come and they protected us. There was such a feeling of goodwill to the film crew and we didn’t have a single incident. In fact we found it harder to shoot in the wealthier suburbs.

What qualifies you as a white director to make a film like Tsotsi?

It’s a question that I obviously face and it would be a lie to deny it. But I never really approached Tsotsi from the point of view that I was telling a story about black people. I was telling a story about poor people, about a kid who has had a bad roll of the dice. I hope one of the reasons the film is working beyond South Africa is that while you might start out thinking you’re watching a film about a black gangster, his inner world is the same as ours is. He’s an abandoned kid who wants to talk about his mother, and that’s pretty universal. My feeling about people is that deep down we want to get a little love, give a little love and have some affirmation of our worth.

But do you understand why some people might have a problem?

I didn’t choose to be white, middle-class and from South Africa, so I have to deal with that prejudice. What draws me is a genuine curiosity about people who are not like me. The privilege and responsibility of filmmakers is we can investigate worlds that are not our own; sometimes that outsider’s eye might be less partisan. I like that; if I stay in my little neighbourhood I don’t get to meet anybody and test my own prejudices. I’m middle-class; am I only supposed to make middle-class movies? I’ve worked in shanty towns, I’ve been mugged myself; am I allowed to tell this story? I think so. And I’m privileged enough to be given the tools to be a filmmaker. Can I use those tools to give dignity to lives that may not get the opportunity to express themselves? I hope what I bring is an emotional experience and a level of empathy and craft.

In the film all the characters speak ‘Tsotsi Taal’, the language used on the streets of Soweto. As a non-speaker, how could you tell what they were saying?

I speak some Zulu and English and Afrikaans which are in Tsotsi Taal, but there’s a lot else in there as well; it’s a language that’s made up of many languages and that is very street. But for me film, is not about the lines; it’s what happens between them. You never want to press an actor for a line reading; what matters is what’s going on emotionally. The universal language is one of emotion and feeling and mood; that’s why you might relate to Tsotsi. His language is part of the whole audio experience, but what’s important is he’s communicating as a person in those circumstances in a universal way. His language is like a wardrobe; it’s not his core.

Was it a deliberate choice to work with new and untested actors?

I like working with first-time actors. It’s tough when you cast because you need that emotional range; my role is to help them feel safe. DW Griffith said that film is the science of photographing thought, which you do by getting the camera in quite tight; it’s about how you help them get their focus off themselves and onto the other actor. All I have to do is help the actor be engaged and generate a river of emotion.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Finally, how do you react to people who compare Tsotsi to City of God?

It’s a flattering comparison because City of God was a superb film. But I was afraid of being accused of imitating that film; I think that is one of the reasons my shooting style is very different. In City of God the handheld camera is appropriate for trying to keep up with these out-of-control kids; my feeling is that though Tsotsi seems to be a gangster movie, it’s actually a far more personal study of one boy, one girl and a baby. It’s a lot more still; it demanded a different style. The comparison that would be more accurate would be Central Station, which was very one-on-one. If I stole, I stole more from Walter Salles than I did from Fernando Meirelles.

The Total Film team are made up of the finest minds in all of film journalism. They are: Editor Jane Crowther, Deputy Editor Matt Maytum, Reviews Ed Matthew Leyland, News Editor Jordan Farley, and Online Editor Emily Murray. Expect exclusive news, reviews, features, and more from the team behind the smarter movie magazine.