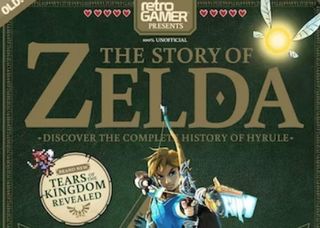

The fascinating, complex and generations-spanning history of The Legend of Zelda

Join us on a tour of the series as we explore what makes it so exceptional, before taking deep dives into each game

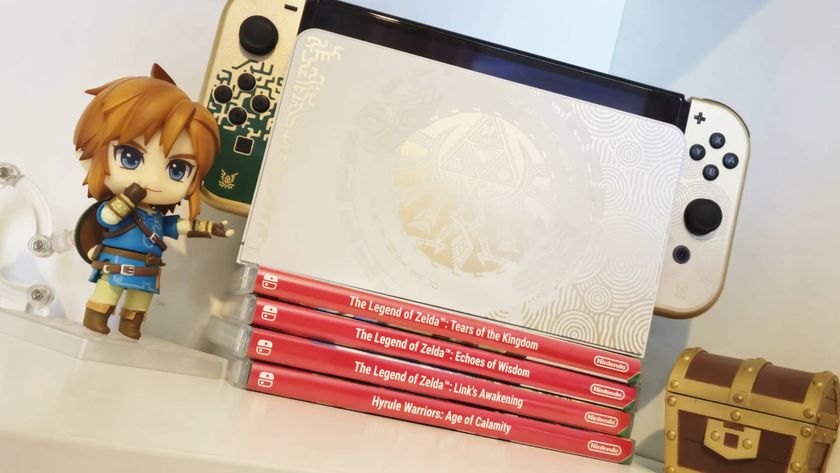

Since his video game debut in 1985 (save for the Virtual Boy), Link has always worked his little elfin boots off to ignite interest in every single piece of Nintendo hardware to ever find a release… and even some of the weird and wonderful contraptions that never left his native home ground of Japan. Even through a dark GameCube period, where seemingly infallible Nintendo IPs were somehow failing to capture that Nintendo magic, there was one licence that has always looked after its Nintendo Seal Of Quality. It's apt, then, that a Zelda game would close out the GameCube's life, and it was the first licence that Nintendo turned to as a 'proper' launch title for its much-hyped Switch.

Before Hyrule, videogames were usually single-screen worlds filled with bleeping and chirping sprites, where progression and skill were distinguished by stamping three letters into a list. And before The Legend Of Zelda, game narratives were generally spared a measly paragraph on an arcade cab or a few dubiously spelt words on a menu screen, and rules and stories would generally play out via easily digestible visuals and an ounce of common sense – escape the ghosts, shoot the crab-looking invader, avoid those asteroids. Off the back of the unprecedented arcade success of Donkey Kong, Nintendo would be able to finance three pivotal projects that would transform it from a Hanafuda card manufacturer dabbling in the world of electronic entertainment, to a leading player in that very market almost overnight: the Famicom, Super Mario Bros and The Legend Of Zelda.

Link'd in

Zelda's development would begin at around the same time as Super Mario Bros, with Shigeru Miyamoto splitting his time between his divided development team and overseeing both projects. His early intention for The Legend Of Zelda was to create a sprawling 'virtual garden'; a video game set inside a lush world that would grow and unfurl. The thinking, at that time, was that Super Mario Bros was going to offer an immediately accessible and technically unique gaming experience, and The Legend Of Zelda would offer gamers the freedom to essentially shape their own adventure.

Despite this peculiar juxtaposition of projects inside the camp, Mario and Zelda would both decide to do away with the element of quick-play high-score chasing and instead replace it with the notion of completion – ending the gaming experience and unlocking a reward screen for your troubles. It was a belief that wouldn't hold up inside the money-feeding world of arcade gaming, but one that Miyamoto believed was perfectly viable in the home. Miyamoto grew up in the small town of Sonobe, in Kyoto, Japan – a picturesque upbringing that would offer the perfect place for his imaginative mind to wander. He was a keen artist with an affinity for music, architecture and design; passions that led him onto an academic road in industrial design and as a staff artist for Nintendo. But it was his fascination for exploration that he would try to impart to the player through Zelda.

His inspiration behind the dungeons – now a staple of the Zelda series – came from the many hours he would spend playing around the rooms of his home as a boy, and the crystal lakes and bountiful greenery of Hyrule from his recollections of exploring the vast fields nearby. Miyamoto's decision to use the name 'Zelda' was allegedly inspired by the wife of the American author F. Scott Fitzgerald. Famously dubbed "the first American flapper", it was her wilful nature that Miyamoto would find so endearing, and persuade him to select her as the muse for the titular princess.

As with Donkey Kong and Super Mario Bros, Miyamoto would polarise Zelda's story around three central characters: a hero (Link), a heroine (Princess Zelda) and a villain (Ganon). Again it would look to an unusual hero (a young elf-like boy) to embark on the quest. Link's involvement in the story comes about after he spots an old woman being attacked and quickly jumps to her aid. He discovers that the woman's name is Impa and that she is a porter to the Princess Of Hyrule. He then hears news of the ensnared princess at the nefarious trotters of Ganon and learns of the warlord's evil intentions for the Triforce and the land of Hyrule.

Link duly agrees to seek out the eight segments of the Triforce Of Wisdom and ventures to the top of Death Mountain where Ganon awaits. In the first game, the Triforce is described as 'three magical triangles' capable of granting great power to their bearer. But its mythology and origins would continue to evolve throughout the series. Essentially, the Triforce is the catalyst, the object of desire that brings and binds the story and characters together. Inside Hyrule, there exist three parts to the Triforce: the Triforce Of Power that Ganon acquires during his siege on Hyrule castle, the Triforce Of Wisdom, which is the part Link is seeking inside the dungeons beneath Hyrule, and the Triforce Of Courage, which would first make an appearance in Zelda II: The Adventure Of Link.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Famicom daze

"I remember that we were very nervous because The Legend Of Zelda was our first game that forced players to think about what they should do next".

The Legend Of Zelda was first released in 1986 on the Famicom Disk System, a secondary disk drive that made use of rewritable disks, which never found a release outside of Japan. In the west, the game came pressed on majestic gold cartridges that incorporated an internal battery facility to save game data, and it would become the first game cartridge to do this. Miyamoto's notion to have the game feel completely bilinear was very apparent. Dropped into a huge overhead world, paved with little direction, it would be left to the player to decipher Zelda's modus through consideration and natural exploration alone; a mantra that actually caused a bout of anxiety in the prolific game designer when the game was eventually released.

"I remember that we were very nervous because The Legend Of Zelda was our first game that forced players to think about what they should do next," Miyamoto revealed to Superplay magazine. "We were afraid gamers would become bored and stressed by the new concept. Luckily, they reacted the total opposite. It was these elements that made the game so popular, and today, gamers tell us how fun the Zelda riddles are, and how happy they become when they have solved a task and proceeded with the adventure. It makes me a happy producer!"

But Miyamoto needn't have worried. Graduating with honours alongside its developmental classmate Super Mario Bros, The Legend Of Zelda would go on to be successful for Nintendo, eventually grossing sales of six million copies. As with Donkey Kong, Nintendo was quick to churn out a sequel while the popularity of the game was still in its infancy. A year later, Zelda II: The Adventure Of Link was released. Although Miyamoto would oversee the game's development, its creation would fall to a new development team, one who would switch the action from overhead to a side-on perspective and bathe it in subtle Mario-esque platform undertones – a change that proved to be unpopular with fans of the original. Its structure would remain generally similar to the first, though. It is another 'find several somethings' (nine crystals) to open 'something' (the Great Palace) that holds 'something with wish-granting properties' (the Triforce Of Courage) – and this is a structure that has been mirrored for almost every game in the series.

The Adventure Of Link would also introduce a few staples of the role-playing genre that would never really take off in the series. Link, for instance, could earn experience points to beef up his attacks, raise his stamina and also obtain magic points to cast spells. Additionally, the game also introduced village sections, where Link gathers information from locals wandering around the town, laying down a foundation for the many games that would follow. In 1990, a new Nintendo console, the SNES, was breaking into the market rapidly. An early and pivotal partnership with Capcom – securing the machine ports of both Street Fighter II and Final Fight – bolstered by an impressive debut by Super Mario Bros would have everyone eagerly anticipating the end of Link's four-year absence from video games. And Nintendo certainly wouldn't disappoint. Released in 1991, and into a swathe of praise, A Link To The Past is cited by many fans as the seminal game in the prolific Legend Of Zelda franchise.

Super debut

The first two Zelda stories were the creations of Shigeru Miyamoto and fellow Nintendo game designer Takashi Tezuka. However, for A Link To The Past, Miyamoto would enlist the writing talents of producer Kensuke Tanabe. Link's SNES debut would mark a return of the popular overhead look of the first game, as well as introducing some loving tweaks to the visuals and controls. Link could now move diagonally, run (with the aid of Pegasus Boots), and the range of his sword attack was also improved. Perhaps the most notable aspect came from the game's deft use of its items. There was the new Hookshot, which Link could use to stun his enemies and pull himself across large gaps in the ground, the bow (which made an appearance in the first game but is used to greater effect here) and the Magic Mirror, which Link can use to shift between The Light World: a colourful and lush depiction of Hyrule, and The Dark World: a dank and nightmarish vision painted with skulls, oily looking marshes and menacing-looking trees. The game was packed with a dizzying array of sidequests, subplots and flourishes.

A Link To The Past also marks the first time in the series that the game's three main protagonists: Link, Zelda and Ganon are not the same incarnations seen in the previous games. It's set hundreds of years before the first game – as flipping the back of the box states – our heroes are 'predecessors' to the original Link and Zelda, and this time-fudging has been a running theme throughout the series. This trend which runs through the early games seemed to be for Nintendo to release a Zelda game, set it in its own unique time and then follow it up with a quirky direct sequel. Zelda II: The Adventure Of Link, Link's Awakening, Majora's Mask and Phantom Hourglass are all direct sequels that adhere to this thinking. But for every third game, generally, the player will always be controlling a spiritual descendant of Link inside a game set in its own unique time; A Link To The Past, Ocarina Of Time and The Wind Waker again all back up this belief. It explains why it is that there's this peculiar sense that Nintendo is occasionally rewriting its story, and why characters in certain sequels react and communicate like they're meeting each other for the very first time.

For many, the series would never better A Link To The Past. And yet, despite the huge swathe of popularity that the game would glean, the Super Nintendo would receive only one western Zelda game in its lifetime. Nintendo would still cash in on the game's popularity in the east by releasing two Zelda-based games on its Satellaview system – a peculiar satellite modem for the SNES co-developed by Nintendo and Bandai. The first game, entitled BS: The Legend Of Zelda, was a downloadable four-part episodic remake of the original NES game but with a few subtle differences. First, the graphics and music were given a colourful facelift and a few elements of the gameplay (such as having it play out in real time, and increasing the capacity of Link's rupee purse) were also tweaked. It's often cited as 'The Third Quest', because of the way it messed with the dungeons, items and the size ratio of the overworld.

To cunningly boost awareness of the Satellaview, Nintendo would also opt to supplant the system's two mascots – a boy in a baseball cap and a girl with red hair – in the shoes of protagonists instead of Link. In 1997, Nintendo released a follow-up to the game, BS The Legend Of Zelda: The Sacred Stones, which again divided the game into four-weekly downloadable chunks. Sacred Stones is considered to be a sidequest to A Link To The Past, owing to the look and feel of the game. It retained the two Satellaview mascots as before and would set the player on a quest to find eight pieces of hallowed masonry and defeat a resurrected Ganon. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Satellaview games is that, like an interactive television show, they could only be played while the game was being aired.

This allowed Nintendo to broadcast hints and tips to the player while they played to help assist them on their quest. As well as the Satellaview, it was always Nintendo's intention to produce a CD add-on for the Super Nintendo. Sony had developed the sound chip for the SNES (the SPC700) and had experience and grounding in CD technology, therefore, Nintendo's looking to Sony to get the project off the ground was really a case of natural selection. However, as the story goes, Sony was determined to break into the videogame market itself and had seen an ideal opportunity to do so when that early contract with Nintendo was drawn up. During that deal, Nintendo signed an agreement that would give Sony the rights to work on a CD-based console that would run both the planned SNES-CD games and also be backwards compatible with Super Nintendo carts. When Nintendo eventually realised this, it decided to attempt to sever ties with Sony and instead strike a deal with one of Sony's rivals: Philips.

After a messy legal battle, Nintendo successfully found a way to pull out of the contract. Eventually dropping the idea of releasing a CD component for the Super Nintendo, Nintendo would give Philips use of two of its IPs for a series of videogames for its CDi machine. Mario and Luigi would cordially appear in the puzzle game Hotel Mario, and Link and pals in three interactive movie-games: Link: The Faces Of Evil, Wand Of Gamelon, (released concurrently in 1993), and Zelda's Adventure (released a year later). The first two games (Faces Of Evil and Wand Of Gamelon) were side-scrolling action games, in the same vein of Zelda II: The Adventure Of Link, but spliced up with dated-looking cartoon sequences. For Zelda's Adventure, the original top-down approach was adopted but the game filled its boots with poorly prerendered computer-generated sprites and absolutely dire acting. Not surprisingly, given the games' prolific heritage, the Philips games were lambasted by the gaming press and fans of the series. Today they stand as weird curious entries, oddities amongst a collection of classics.

Garden statement

"If there were some fans that found it difficult to warm to the direction of Majora's Mask, then the next Zelda game was always destined to put a few noses out of joint".

"Instead of thinking of it as making a game, think of it as nurturing a miniature garden called Hyrule," Miyamoto once said about the making of The Legend Of Zelda: Ocarina Of Time. Ironically, many fans of the popular series would view Ocarina not as a brilliant nurturing of Hyrule but as a brilliant nurturing of Link. Released in 1998, and built from a drastically modified version of the Super Mario 64 engine, Majora's Mask chronicled the biggest shift in the series to date, the transition from a 2D to a 3D realm, and a longer period in Link's life. Starting out as a boy, between the age of eight and nine, we would see Link's quest lead him into adulthood. But it's clear what Miyamoto was hinting at. Technically jaw-dropping draw distances, real-time light sourcing and expansive environments that could be covered effortlessly on Link's steed Epona and an almost faultless camera and control system; it's true that the world of Hyrule was never so brilliantly fleshed out.

The sequel to Ocarina Of Time, Majora's Mask (2000) introduced many firsts to the series. Originally titled 'Zelda: Gaiden' in 1999, it was the first time, inside the main canon of games, that Nintendo would really break its 'Triforce Of Characters' (the first game to do so was Link's Awakening on the Game Boy). Majora's Mask doesn't include any physical incarnation of Ganon (although his name is mentioned) and Zelda's appearance is relatively brief in relation to the prevailing games in the series. Beginning life as an intended extra section of Ocarina Of Time (had the game been released on the Nintendo 64DD as originally intended), it heavily tweaked the Zelda structure and messed with the series' familiar Hylian setting. As a result, many fans viewed it as the most jarring game in the series.

The graphic style of Majora is essentially Ocarina refined, with many of the same elements wholesale across. The biggest difference between the two Nintendo 64 games is that in Majora's Mask, Link doesn't age (although there's a mask in the game that makes it possible) and the whole episode is set over just three video game days. Link's mission is to prevent the destruction of Termina (a slightly more sophisticated alternative vision of Hyrule) from an ominous moon that in three days will destroy the town. With only three 'days' until the game ends it was necessary for Link to keep travelling back in time, to the start of the first day, until his quest was complete. Oddly, despite the notion of time travel and rebirth being a strong mantra for the Zelda series, some would find it difficult to warm to Majora's confining time-travel structure and oppressive tone. That said, others consider it to be one of the most inventive and atmospheric games in the entire series.

If there were some fans that found it difficult to warm to the direction of Majora's Mask, then the next Zelda game was always destined to put a few noses out of joint. After the infamous Legend Of Zelda: Space World GameCube demo in 2000, which showed an impressively rendered sword fight between Link and Ganon, its sinewy graphical style of an adult Link had many fans believing they were going to get a darker Zelda adventure. However, the game they eventually got would look nothing like the teasing demo unveiled to Space World attendees. Taking the biggest shift in terms of visual style, The Wind Waker's cel-shaded graphics would upset fans who were expecting an epic and mature Zelda appendage. Ironically though, perhaps the biggest shift in the game came from its scrapping of certain Zelda gameplay elements.

Instead of time travel, The Wind Waker uses the wind and the ocean for its puzzle and explorative elements, and rather than one large land to explore, it's split into islands connected by miles of sea that Link must traverse by sailboat. But Wind Waker also had a sense of humour, and took many aspects from the portable Zelda games, with more emphasis on characters and a feeling of being more accessible for newcomers. Its effusive and simple anime-style graphics captured the facial expressions of its characters better than any Zelda game before it, going lengths to invoke emotion, a real connection with Link, and cleverly serving as subtle hints to the player to help them solve puzzles. In a bid to perhaps soften that visual blow to its fans, Nintendo would accompany the game with a bonus disc containing the original Ocarina Of Time and Ocarina Of Time/ Master Quest – a more arduous version of the N64 game that was intended to be released for the Nintendo 64DD.

The cube

Perhaps due to its basic look, the next Zelda game to appear on the GameCube came and went with generally little fanfare. Developed by Nintendo, The Legend Of Zelda: Four Swords Adventures took visual and multiplayer elements from the GBA game, A Link To The Past & Four Swords (see 'A Link To The Palm'), and brought an entirely new squad-based dynamic to the series. Slotting weirdly between two Game Boy Advance games, Four Swords Adventures would form the second game of Zelda's Four Swords trilogy. It allowed one to four players (if you had a link-up cable and knew three people with a GBA) to control four different coloured Links, position them into various formations and tier off to work together to solve the game's colour and teamwork-themed puzzles. The multiplayer emphasis of the game was further bolstered by a unique battle mode that allowed four friends to select a Link and duel to the death.

The next game to appear in Nintendo's popular series was the engaging Twilight Princess, a game that famously carried the weight of two consoles on its shoulders. After a one-year delay, Twilight Princess would prove a fantastic farewell to the GameCube, but sadly a tepid and awkward debut for the Wii. With The Wind Waker, Nintendo's intention was to make a Zelda game that anyone could finish, and as a result, many fans would bemoan the game for being far too easy. So Nintendo looked back to Ocarina as the blueprint for the style and direction of Twilight Princess. Running from a heavily tweaked Wind Waker engine, Twilight Princess looks to be the polar opposite to its GameCube sibling. In hindsight, it's actually a culmination of ideas and themes from the later Zelda games. It clearly borrows from Ocarina Of Time in terms of its visuals, adopts the darker tone of Majora's Mask, and boasts the scale and gameplay tweaks of Wind Waker – with regard to its cinematic look and continued use of facial expressions.

It was decided, mid-development, that the graphical style of the game would be altered. Early shots of the game showing Link inside a grey and desaturated world would reaffirm to fans that Twilight Princess was to be a darker direction for the series. However, the eventual graphical style would shift to a hazy world made of warm serene palettes, but that darker direction was kept. The game also contained more dungeons and more items than Ocarina Of Time, as was the intention by Nintendo to finally offer the hardcore Zelda fan a game to really test their mettle. While the Wii version is essentially an enhanced port of the GameCube release, the game would actually play out slightly differently; the game worlds were mirrored. Link has always been left-handed in the game, and if you were to look closely at the series, you'll notice that whatever direction Link is facing he will hold his sword in his left hand. With the advent of the Wii-remote controls in Twilight Princess, Nintendo realised that many players would be right-handed so would make Link a mirror to the player in the Wii version, and the game world would follow suit.

With the exception of Link's Crossbow Training, a short game packed in with the Wii Zapper as a means of demonstrating the peripheral, Link would not return to the Wii for several years. In the meantime, the cartoonish Link of Wind Waker and Minish Cap continued to adventure on the Nintendo DS. The first of these was Phantom Hourglass, a successor to Wind Waker which retained much of the game's seafaring action. Link's pirate pal Tetra goes missing after the pair happen upon a ghost ship, which kick-starts a quest to save the girl and uncover the mystery of the phantom vessel. The biggest change was a touchscreen control method that saw players directing Link and performing combat moves using the stylus. Though some players disliked the lack of traditional controls using the d-pad and buttons, Phantom Hourglass received critical acclaim and sold over 4.1 million copies.

Given that success, it's unsurprising that the Zelda series returned to the DS in 2009 with Spirit Tracks – and once again, the stylus was the main input device. Instead of sailing the high seas, Link now found himself riding the rails as a train engineer with a mean sideline in swordplay, trying to discover why the titular Spirit Tracks that connected the kingdom were disappearing. Though this might seem a little out of place in a series that has usually had a fantasy focus and not drawn too much attention to technology, director Daiki Iwamoto was deliberately aiming for a different feeling to a regular Zelda game. The result was another success, though with 2.6 million sales it didn't quite match up to its predecessor's popularity.

Though Link's next game was not a new one, it generated considerable excitement as it was a remake of the game many still considered to be the greatest in the series. Ocarina Of Time 3D was a full visual overhaul of the N64 game for the 3DS, designed to take advantage of the added sense of depth offered by the new handheld hardware. The game was both a critical triumph and a sales success, selling over a million copies, but bigger things were coming as the Zelda series was about to return to the home console arena. The Wii received Skyward Sword in 2011, making it a relatively late release in the console's life. Though Skyward Sword was not nearly as dark in tone as Twilight Princess, it didn't veer back into the overt cartoonishness of the cel-shaded Wind Waker. The tone was pitched closest to that of Ocarina Of Time, with a slightly more vibrant colour palette. The game is also the earliest in the Zelda story chronology, with Link and Zelda cast as childhood friends. When Zelda is kidnapped and taken down to the Surface, Link becomes entangled in the evil Ghirahim's plot to free the demon king Demise, and must prevent it to save Zelda and the world.

In order to add extra precision to the Wii controller's motion-sensing capabilities, Skyward Sword made use of the Wii MotionPlus add-on. The more accurate tracking played heavily into combat, with the Wii controller used for the sword itself and the shield controlled using the Wii Nunchuk. Likewise, the bow was now fired by pulling the remote back as you would the string in actual archery, and bombs could be rolled towards targets like bowling balls. Despite some reservations over the implementation of this new scheme, as well as a feeling that the rest of the game development community was finally beginning to catch up to the 3D Zelda mechanics, most reviewers were overwhelmingly positive about the game and it sold millions in short order.

Though the Wii was succeeded by the Wii U in late 2012, there was no early Zelda release, so GameCube remasters were released to plug the gap, Wind Waker HD in 2013 and Twilight Princess HD in 2016. Instead, new developments would take place on the 3DS, though they would also mine the past for inspiration. A Link Between Worlds was released in 2013 and served as a successor to A Link To The Past. Link's task was to prevent the theft of Hyrule's triforce by the inhabitants of the parallel world of Lorule, who seek to restore their kingdom after it falls into decay due to the destruction of their own Triforce. One fun mechanic introduced here was the ability to merge onto walls as a mural, allowing Link to cross otherwise impassable gaps. It was an excellent game and went on to sell over 4.2 million copies.

The final stretch

"I think many people dream about becoming heroes".

The next game to release was Majora's Mask 3D, another 3DS remake in the fashion of the previous Ocarina Of Time 3D. This sold over 3.3 million copies and was easily the most exciting Zelda development of 2015, as the year's other 3DS release was a rare misstep for the series. Tri Force Heroes focused on multiplayer cooperation in a similar manner to the prior Four Swords games and allowed players the option to play alone, via local wireless and even online. However, the game was stifled by its need to cater to the friendless, with few challenges truly testing a truly organised team. Additionally, much of the design was lifted from prior Zelda games with little innovation. Likewise, the spin-off Hyrule Warriors on Wii U was little more than the Dynasty Warriors games with a new skin, though it was popular enough to see a few sequels.

A lack of innovation is not something that troubled the most recent major game. Though it began life as a Wii U game and was revealed as such in 2014, Breath Of The Wild ended up carrying a new piece of hardware to glory, as the Nintendo Switch ended up as the system that most players would use to experience it. Released in 2017, the game was a radical reinvention of the series, taking the game's trademark mechanics and fitting them into an open-world design that draws strong influences from games such as Assassin's Creed. This game saw Link awakening from a long slumber to find a world in ruins, having been sealed away by Zelda following a heavy defeat by Ganon. To end the tyrant's influence over Hyrule, Link's goal was to defeat the Divine Beasts that had been corrupted by Ganon, release the spirits of the kingdom's champions and then slay Ganon himself. Breath Of The Wild was a critical success and also the best-selling Zelda game ever. A anticipated sequel, Tears Of The Kingdom is due this year.

So what is it that makes the Zelda series so popular? Why does every new chapter create such an air of excitement surrounding it? Why do people meticulously dissect every screenshot, analyse and pore over every Zelda-related rumour and await the next chapter more so than any other video game franchise to date? Miyamoto sums it up perfectly. "I think many people dream about becoming heroes", he told Superplay magazine in 2003. "For me it has always been important that the gamers grow together with Link, that there is a strong relationship between the one who holds the controller and the person on the screen. I have always tried to create the feeling that you really are in Hyrule. If you don't feel that way, it will lose some of its magic."

Keep up to speed with all of our celebratory Zelda coverage with our The Legend of Zelda celebration hub

Nick picked up gaming after being introduced to Donkey Kong and Centipede on his dad's Atari 2600, and never looked back. He joined the Retro Gamer team in 2013 and is currently the magazine's Features Editor, writing long reads about the creation of classic games and the technology that powered them. He's a tinkerer who enjoys repairing and upgrading old hardware, including his prized Neo Geo MVS, and has a taste for oddities including FMV games and bizarre PS2 budget games. A walking database of Sonic the Hedgehog trivia. He has also written for Edge, games™, Linux User & Developer, Metal Hammer and a variety of other publications.