Head Trip: Double Fine takes our brains to another dimension in the psychedelic Psychonauts 2

Diving into the weird and wonderful world of Psychonauts 2 with creator Tim Schafer

The shock of the new is important to Tim Schafer. "The challenge when making a Psychonauts level is coming up with something that makes you feel like you haven't seen it in a game before," he says. In that regard, we'd say what we've played is a qualified success. It begins at a music festival called Feast For The Senses, and that's a tacit promise on which Double Fine fully delivers. Via a kaleidoscopic transition, we're transported to a woozy, substance-fuelled brainspace that makes us feel lightheaded.

With a psychedelic rock-inspired soundtrack noodling away in the background and shrewd use of chromatic aberration giving the world's angular lines and edges a fuzzy, soft-focus feel, it's a trip in more ways than one. But though we might not have been here before, at the same time there's an undercurrent of homecoming: a strange, comforting sensation that steadily washes over us.

Now we feel transported in a different way, back in time to 15 years ago, and another game that took us to places where real-world rules no longer apply. Psychonauts 2 certainly does offer something new, but it also gives us something equally precious: more Psychonauts. A degree of continuity is exactly what Tim Schafer and Double Fine are aiming for. Not least since the story begins pretty much where we left off – or exactly where it left off, if you played two-hour VR adventure Rhombus Of Ruin, which itself ran on from the end of the first game.

If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

"It's like the third day in this story," Schafer says. As before, we're controlling Raz, a former circus acrobat with psychic abilities who can astrally project himself into another person's mental world. The level we play kicks off at Psychonauts headquarters, when Raz finds a brain in a jar abandoned in a storage room.

"It's been alone for 20 years, which has caused it to shut down a little bit," Schafer explains. "So when Raz goes inside, he finds it's all blackness except for a tiny little mote of light who can't remember anything." To restore the memories of this brain, Raz finds a convenient body for it to inhabit, causing a flood of sensory information. As the frontman anxiously waits in the wings while a baying audience throws tomatoes at the empty stage, Raz must reunite the rest of the group – each member representing one of the five senses – before the crowd gets really angry.

That suggests an urgency that's lacking from the first part of the equation at least, which involves frontman Vision Quest, a humanoid figure with a giant eye for a head. Naturally, we're soon subsumed into that same eye, and we emerge blinking into a green-tinged world of stacked amps, scattered microphones, spotlights and other stage props. Around those we find extended mic stands that double as grind rails as well as spinning fans, on which you'll find phrases like "perception is reality", alongside fish swimming through the air and – of course – clusters of mushrooms to jump across.

Mind over matter

Even without stimulants it feels like a consciousness-expanding experience. What follows is, for the most part, an easygoing delight. It's quite early in the game ("Not the first level, not the second level," Schafer muses; "It's right in the middle – well, early middle.") and it's all fairly relaxed.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The original game's Censors are present, those fragments of a person's psyche that try to maintain order in a chaotic mind. Yet as they scamper up with their little stamps, they seem more harmless than usual, and are easily dispatched with a swipe or two of Raz's basic melee attack. That there's little to be afraid of is in keeping with the mellow mindset of the host, naturally, but when we mention its lightweight challenge to Schafer – as an observation, not a criticism – he quickly insists that this won't be the case for every level. "

It feels like the right amount of combat for where you are, just like, a little bit of it here and there. But it definitely ramps up throughout the game."

Here, instead, you can focus on exploring and platforming, which feels appreciably tighter than it did in the original – as, 15 years on, you'd hope it would. Raz still has several of his original Psi powers, which are bound to the bumpers and triggers, though there's little call for many of them here. Psi Float carries us across a few larger gaps that a double-jump alone isn't enough to reach, though some require use of a brand-new ability: Time Bubble.

As your glowing partner explains, he's been alone for so long that time no longer has any meaning. "He basically has the ability to form time to his perception of it," Schafer explains. "Which, in practical terms, means you get to slow things down in the world." And so we use it on a rapidly spinning fan to leap between its blades while one of those flying fish becomes a stepping stone to a platform.

The light (whose real identity is a secret) has spent so long alone that he's initially confused by this sight. "Is that a fish? I think it's a fish! Or a bus?" it says, adding as we step off, "Well, you rode on it so I guess it's a bus."

His chatterbox commentary makes the journey even more enjoyable, not least because Schafer's lines are being delivered by the inimitable Jack Black. This marks their third time working together after Brütal Legend and Broken Age, and it's a collaboration that continues to strike comedic gold. "I know what this is! A blender, right?" he chirps as you approach a spotlight. Then, as you turn it towards a prism to create a rainbow bridge, realisation sets in. "Oh no, you're right, it's a lamp." Then, after a perfectly-judged beat: "A lamp for making drinks."

If it's a revelatory experience for both player and mystery light ball, for the latter it all becomes a bit too much too soon. And when Raz tells him not to panic, it's the worst thing he could have said. The word triggers the physical manifestation of a panic attack, a jagged, jittery creature appearing that skitters about inside a large arena. It's Raz's job to take it down, and we do it without too much trouble, slowing its rapid movements with our newfound skill before smacking it around and repeating until it's gone. Panic over.

Amid the relative calm of the rest of the stage, it feels – as it should – like an anomaly, a sudden and dramatic burst of nervy activity when you least expect it. It comes on, in other words, just like a real panic attack. It's a reminder, too, that the original Psychonauts was examining mental health issues long before it became de rigueur to speak more openly about them.

"I mean, I don't think we did everything perfectly and I think we've learned a lot since 2004," Schafer says. "But our instinct was definitely not to make fun of mental illness. The whole thing about Psychonauts is that you'll meet somebody who's doing something negative: they're behaving badly, they're being really aggressive, they're acting like a jerk and you don't know what's going on."

"And the tendency is to write them off as an enemy, but in Psychonauts you go into their brain, and you find what's going wrong in there, you find out that they're wrestling with this traumatic memory or this demon in their mind, which is just an abstract form for a neurosis or a psychic construct of some kind, and you help them fight it."

Even Coach Oleander, the first game's antagonist, achieves some kind of redemption. In the final stage, you discover the brutal truth behind his inner demons, entering his brain to finally defeat them.

"I think everyone in this world is usually redeemable," Schafer adds. "Because it's very easy, I think, to write someone off as 'crazy' – to use that word and be like, 'I don't want to deal with them anymore as a human being.' Psychonauts says a lot about how we all have these things in our brain that we're wrestling with, and you can look for what they're afraid of and help them work through it."

If all this seems obvious now, he admits that it was something of a happy accident; a natural by-product of its imaginative conceit. "I don't think we articulated that as a deliberate thing. I think it's only looking back on it that you're like: yeah, that's what the spirit of that game was."

"You can have a lot of different ideas for a Psychonauts level just by meeting people in the world."

Tim Schafer

Psychonauts 2 certainly captures that same spirit, along with the imaginative visual flourishes that burned the original so indelibly into memory. One of the highlights here is delivered almost effortlessly.

Without fanfare, as you pass through a series of arches (instrument cases, amps, a twisted steel truss) the world suddenly curves up and over in a manner not unlike Animal Crossing's old rolling-world effect, revealing a large open area overseen by a huge, Vishnu-like, four-armed statue of Vision Quest. Well, as Black observes, frontmen do tend to have big egos. It's one of a handful of reminders how much effort goes into making a single level in a game like this.

"There's a lot of bespoke creation," Schafer says, "A lot of one-off things – you know, cutscenes, different art styles." Indeed, though the opening sequence makes it apparent that this is just a temporary shift in aesthetic, he's amusingly concerned that we might think the entire game uses this same look, hitting us with a barrage of questions: "Did you have that? Did you think it, too? Did you also think that was gonna be the look of the whole game?"

We respond with one of our own. Where does Double Fine start when making a level like this? The answer is a long one, and it goes right back to the beginning. When we say this is a sequel 15 years in the making, that's no hollow claim. Technically it's only been five years since plans were announced for a sequel, and the game's crowdfunding campaign on Fig began. But Schafer has been coming up with ideas for a potential follow-up ever since the first launched.

"The fun thing about a Psychonauts game is that anytime you meet a strange character or interesting personality, you can imagine, like, what colour is the sky in their world? What does their mental world look like? What does this person's brain look like inside?" he says. "You can have a lot of different ideas for a Psychonauts level just by meeting people in the world."

As a result, he's kept a Google Doc open ever since, thinking up potential concepts and considering the effects they might have on a person, or simply jotting down aesthetic ideas. For this particular stage, The Beatles' film Yellow Submarine was a big inspiration. "Do you know that's not their voices?" Schafer says. "I didn't know that until I was an adult. I just thought that was The Beatles, and it's not The Beatles. It's ridiculous."

German-American pop artist Peter Max was another, art director Lisette Titre- Montgomery reminds him. And as senior concept artist and level lead Emily Johnstone recalls, the most crucial ingredient was one word written on a note card: synaesthesia.

"It's an amazing phenomenon," she says, "But when I saw it I thought, I'm not sure if I want to touch this with a ten-foot stick because in video games it's really hard to illustrate that idea." Schafer laughs. "Yep, you said you didn't want to touch it with a ten-foot pole. So we assigned it to you."

Mental gymnastics

Building any Psychonauts world is a deeply collaborative process, Titre- Montgomery explains. "Once we have an idea of what the central pillars of the level are, we start collecting references and shaping the vision before Emily and our team of concept artists start riffing on what that means. And meanwhile, we're working with our design team to figure out the mechanics that support the story, and which of Raz's powers also help with that."

In this case, an unconventional level – not that there is such a thing as a conventional Psychonauts level – with such a distinctive aesthetic demanded a different approach.

"In the early days, we had access to Oculuses and PSVRs and I was painting in Quill," Johnstone says. "I was thinking of a world that was very green and had this very shapey visual language, and that painting ended up inspiring a lot of what this ended up being. I'm traditionally a 2D concept artist, but it was really helpful to our designers and world-builders to get a sense of what this world in particular would look like in a three-dimensional space."

As each world takes shape, the script goes through a series of passes, too. "When the interactivity of the level starts to really come on, then I can do the real writing," Schafer says. And when a level is closer to completion, playing through it again often prompts bonus dialogue.

"The artists will put in some amazing visual thing, and I'm like: well, Raz has got to talk about that," he says. "There's a lot of back and forth between the level designers and Tim. It's all about building on the things each of us puts in," Johnstone says. "I call it writing algebra," Titre-Montgomery adds. "We have to solve x at some point before it's all stitched together." Schafer laughs. "It's like a big jam session of a psychedelic prog-rock band."

Double Fine staff are also invited to contribute via a Slack channel for which Schafer has invented a new adjective: Psychonautical. "It's basically weird, trippy things that make you think about mindexpanding experiences and alternate frames of consciousness and all those kinds of things as inspiration." No idea was too out-there: if the first game's worlds broke conventional design wisdom, Schafer wanted to push things even further this time.

"There were other things like the music," he begins; instantly we hear the level's melodic hook, played on an electric violin, start another loop inside our head, so quickly has it wormed its way in. "Camden Stoddard, our audio director, and Peter McConnell, our composer, were thinking about psychedelic music," Schafer says, as we're about to drift into a reverie.

"It was really fun watching Peter and Camden and everyone talking about Crimson And Clover, that one part where the reverb is really crazy, and it adds so much to this level," Johnstone enthuses. "It was all about evoking that same wonder, that Yellow Submarine feeling, as you're navigating through the space," Titre- Montgomery adds. "We really wanted to dig into the psychedelic lore of the '60s as much as we could to evoke that feeling."

That's a lot of work for just one level. Multiply that several times over and you have an idea why it's been five years and counting since development started, and the finish line is still a little way off yet. It's not the first time a Psychonauts game has undergone a change of publisher – ironically, it was Microsoft, which dropped the original, that came to the rescue this time – and the appeal of making a sequel made Schafer forget just how much trouble the first game was.

"After Broken Age, I was like, 'I want to do a big game again, I want to make a big world again,' and now I remember how hard that is," he laughs. "Every level has to feel really fresh and that we're doing something interesting. That's the hardest part. A level might work, it might be functional, but if it has a certain ho-humness about it, it's back to the drawing board and that's often what takes the most time."

Still, he says it's to his team's credit that he's struggling to come up with a single example of being told any of his ideas has been unachievable: in fact several, he says, went straight from that early document into the game. Some elements have been mixed up – Schafer's note cards were scrambled and rearranged until specific combinations jumped out – but even the most ambitious ideas have somehow come to fruition.

"We always dream big," Johnstone says. "And then we try to figure out a way to represent an idea in some way. Maybe we don't get it on that first pass, but we work it out creatively and people are like, 'Oh my gosh, we're going to do that?'"

Titre-Montgomery nods. "We start with the moonshot, as they say in startup language, and figure out how we do it with the technology we have. How do we balance the emotional moments of this while trying to tackle production and timing and resource schedules?" Problem by problem, she says, it's been a team effort to work it all out. "One of the best things about this game is that I'm the most creatively challenged I've ever been in my career," she says.

Which isn't to say that Double Fine doesn't appreciate the art of trimming the fat. "Editing – good editing – lets you focus on what's important in the game," Schafer says. Is that why the cutscenes are kept so brisk? Much of the storytelling here is done on the fly, through exchanges between Raz and Black's character, while any cinematics feel short and snappy.

Schafer suddenly beams with delight: "It's great to hear that because I'm always sensitive about having too many cutscenes." Where does that come from? It goes back, he says, to watching the very first playtest of The Secret Of Monkey Island. "It was text-only. So they'd read one line of dialogue, two lines, three lines, and every time after the third line of dialogue had gone by, I'd see their finger tapping the mouse like this: ta-tap, ta-tap, ta-tap, ta-tap. I was like: Oh my god, they're getting antsy. So that's why I'm always trying to keep them as short as possible." The dream, he says, is to have a seamless flow between action and cutscenes, and here he cites an unexpected influence: "You know, like the big games like Uncharted do really well."

We're sure Schafer's publisher won't mind too much that he picked a PlayStation exclusive; indeed, just as we're discussing editing, he praises them for letting him add a feature back in that was otherwise certain to be cut.

"At a certain point, the finiteness of the money was very much in our face," he says. "Boss fights were last on our schedule, and they were kind of disappearing from the game." Then the acquisition happened, and Microsoft asked him a question. "They said 'What would you do if it wasn't for fear?'" he laughs. Those extra resources meant that Double Fine could "finish the game in the style that it was meant to be finished in", Schafer says. "For me, that meant putting the bosses back in."

Those of us old enough to recall the first game's encounters are unlikely to begrudge Double Fine extra time to push Psychonauts 2 across the finish line – after 15 years, we're happy to wait a little longer. But we still can't escape the sting of frustration when the 'Thanks for playing!' message pops up as Raz gets his hands on Vision Quest's violin.

"What did you think?" Schafer asks. We confirm that it ranks low on the ho-humness scale; we just wish there was more of it to play right now. He leans back in his chair, a broad grin spreading across his face. "Well, then," he says. "Mission accomplished."

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at Magazines Direct.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.

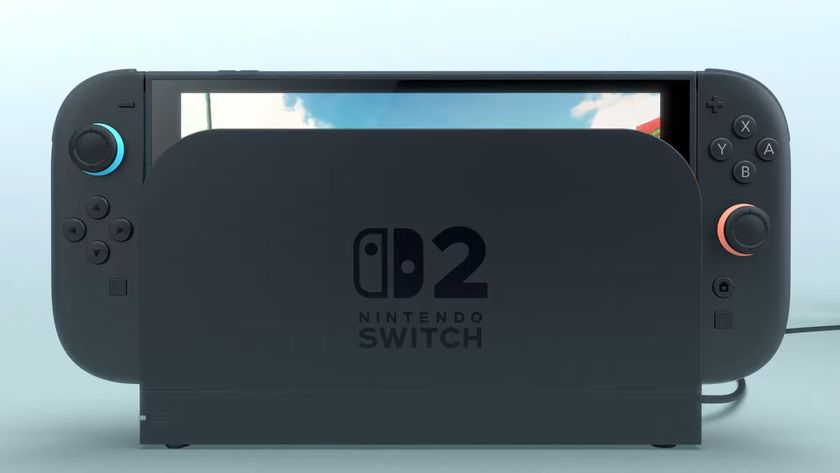

Ex Nintendo PR managers say the Switch 2 generation is likely to see the retirement of "several of the major developers at Nintendo who we have known for 40 something years"

Helldivers 2 CEO says industry layoffs have seen "very little accountability" from executives who "let go of one third of the company because you made stupid decisions"