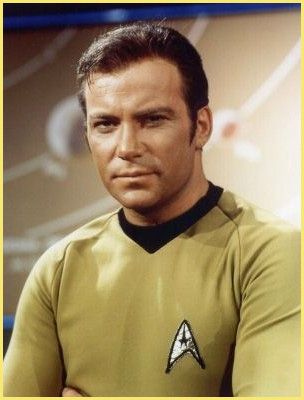

HAPPY 80TH, WILLIAM SHATNER!

None

In tribute to William Shatner's 80th birthday, here's a classic SFX interview from 2002.

As I shake the hand of William Shatner I fear I may be exuding a pink and fragrant ooze.

It's more than mere nerves; an hour earlier I had stood in a Paddington toilet and, like a dope, confused a hand-dryer with a soap dispenser. The evil, petal-scented slime had seeped into my suit, dribbled onto my shoes and congealed around my fingers, mocking me with an anti-bacterial cackle. And then, as I'd frantically blotted it with some hopeless scrap of tissue, on the cusp of panic beneath the merciless light of the gents, my one consuming thought had been, "Oh God, no...Shatner!"

Shatner. This means something. Another flashback for you, in a way more humiliating than the last: the night before the interview I had walked the cold, Christmas-bright streets of Bath with the soundtrack to The Wrath Of Khan in my headphones. I had no destination but pure nostalgia. It felt tragic but deeply right. Professional detachment be damned. I wanted to stir my fanboy blood. I wanted to know - truly know - that I was about to meet a childhood hero, an old action figure made flesh. I was about to meet Captain James T Kirk of the starship Enterprise.

Kirk. He was John F Kennedy, Elvis and Neil Armstrong, leader, love god and astronaut, an American icon who promised us that the noble arts of wenching and bare-knuckle brawling would endure to the 23rd Century. No chiffon-robed honey was safe from his testosterone-fired loins (he put the moves on the entire known universe); no cosmic fiend could survive his killer right hook (he wrestled giant space lizards). As cool as a quiff, Kirk conquered the final frontier in the name of small boys everywhere. Yeah, he was my hero.

And now here I am, extending a hand that may foam violently at any second.

"Is that a tape recorder?" asks Shatner. "Or will you shoot me at the end of the interview?"

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

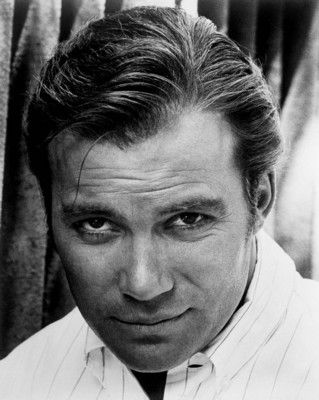

He's an astonishing 71, possessed of an energy that seems to dispute his years. Small boys, breathe easy - Kirk is still there beneath the neat, frameless spectacles and the surprise of a beard. I ask if everyone greets him with a big, dumb smile. I know that I certainly did.

"A big, dumb smile? I don't think it was dumb. You had a nice smile. It was friendly, and you were clear-eyed, and you looked me in the eye, and you shook my hand firmly, and I thought you were obviously a good, honest fellow."

I'm being ever so gently ribbed, aren't I? Shatner is puckish and twinkling. This is something of a relief. There's a popular perception - stoked by the grumblings of former colleagues - that Shatner has an ego the size of Mount Kilimanjaro. The media occasionally daubs him as touchy and truculent. I knew that my childhood memories could all too easily be napalmed. But no. Shatner is all warmth and easy charm today, in spite of a punishing PR blitz that has hurled him from Richard and Judy to So Graham Norton . He has flown to London to promote Star Trek - The Adventure , a huge, interactive exhibition at Hyde Park, but he's willing to offer a cup of coffee, share sugary pastries and talk about kicking Ed Norton's ass.

"Yeah, I saw Fight Club ..."

Ed Norton's runty urban pugilist famously declared, "Shatner...I'd fight William Shatner..."

"I just fell down laughing. It was very funny. It's kind of interesting - I wonder why they chose me? I really don't know why. Because it was a measure of his ability to fight, as if fighting me would have given him some measure? And actually the skinny little kid could not have beaten me..."

Why did they choose him? Perhaps it's because the words 'William' and 'Shatner' have become a convenient punchline for ironists everywhere. A hero to some, a ham to others. Surf for his name on the net and you will unearth a surfeit of send-ups, some fond, some vicious, from The First Church Of Shatnerology to The Incredible Stripping T J Hooker. Blame the inimitable, staccato delivery, the tendency to glorious, planet-chewing performance, the years mired in such tosh as Kingdom Of The Spiders or simply The Transformed Man , his cracked assault on such 60s pop gems as Lucy in The Sky With Diamonds and Mr Tambourine Man. His deadpan, self-mocking turns in Airplane 2 and Free Enterprise suggest he is in on the joke. I'm tempted to believe that he may even have started the joke, but then he tells me, without a molecule of irony, that the "one-line concept" of his new album is "the human condition", and suddenly I'm not so sure.

So how does it feel to be cultural currency? "Cultural currency?" Shatner smiles. "Well, in the EU, I'm a Euro, and yet I have a...yen...to be something else. Solid as a dollar. And the buck I won't pass."

Does it ever feel like baggage? "Yes, but I can ship it. Someone else will carry it, or Fed-Ex will take it. I don't feel like I'm trailed by things that I can't carry."

What's the biggest preconception about him? "That I'll disappear in a swirl of fairy dust."

It's a volley of smirks and smart replies. Shatner is jousting, side-stepping serious questions with a nimble, well-honed flippancy. This might be a short interview. And then I mention his roots in classical theatre, and I ask if he regrets trading serious, fulfilling drama for pop culture, and he's instantly thoughtful.

"You know, it's all one thing. I don't see a variance in it. I was at Stratford a few days ago - this is Stratford, Canada, I wasn't holding a skull in my hand - to receive a philanthropic award for my work with horses and handicapped kids. I was up on the stage that I'd been on years before, and I spoke to an audience, and I moved them. Now two weeks earlier, an old friend of mine, Christopher Plummer, had played King Lear on that same stage. And I remember thinking, 'I wonder if I would have liked to have done Lear?'

"I wondered how I would interpret Lear. I understand Lear much better now than I would have done 30 years ago. The older you get, the closer you get to death, the more you understand what Lear was attempting to do. And at the same time I thought...that's an awful lot of work! I know that physically and vocally I would have to be in training for maybe six months. Learning those lines is a real effort. There's the apprehension of missing a word or two here and there. And then you've got to get it up eight times a week - which I have done innumerable times in my life..." Again, the incurable smirk.

"You're asking me if I'd rather have the satisfaction of heavy duty acting assignments, and my sum answer to that is...yes and no. I love the idea of it, but I'm also totally engaged with what I'm doing. I'm happy speaking to a large group of people and moving them by words other than Shakespeare's, by performing in films that are interesting, by writing and directing films that I want to do."

He may not miss Shakespeare, but he surely misses the sheer ball of playing James T Kirk. Does he never feel the character fighting for existence inside him, demanding "I...must...live!" in suitably Kirkian fashion?

"When I played that part, the scripts came so late that there were times when I was only handed the pages I had to perform when I walked on the set. In some cases I didn't know what the entire plot was, or what my relationship was supposed to be with the person I was acting with. I had no idea where it started or where it ended, because those pages didn't exist; they were being written even as we spoke. So the character of Captain Kirk is pretty much close to me. It isn't like I had time to put an artifice, a lens, in front of myself. What did Popeye say? 'I yam what I yam.'"

But when the door is closed, and he is quite alone in Chez Shatner, does he never have a Kirk moment?

"What's a Kirk moment?"

A brief, secret burst of Kirk.

"When the door is closed?"

Shatner ponders the question.

"Sometimes in the toilet."

Perhaps his entire life is a pure chain of Kirk moments. Star Trek V - The Final Frontier found Shatner behind the lens, helming a deeply flawed if good-hearted big screen voyage that was ritually slaughtered by the critics. There was something profoundly Kirkian about the way that a hopelessly outmatched Shatner wrestled the lizardy claws of Hollywood, fighting for something good in the face of overwhelming odds and a cruelly torpedoed budget.

"Secretly, in my heart of hearts, I knew that what I had was grand. What I got right was the concept. Star Trek goes in search of God - that was a good idea. What a grand canvas to think about, but what I didn't know was how to politically push those ideas through. Gene Roddenberry said to me, 'God won't work.'"

Ironic, given that Gene Roddenberry had a whole drawer of unused scripts in which the Enterprise discovered God.

"That was exactly right. Who knows what lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows..."

First Popeye. Now The Shadow. He'll be quoting Captain Kirk next.

"I also wanted the characters to be in conflict, and that would be resolved by their love for one another. And there was a messianic character, with an army of followers, which presaged all that's happening now in the world. So I got all that right. And then all of it...went wrong!"

Shatner erupts with honest laughter. "There was one moment when I turned to the producer - we were looking at rushes - and I said, 'God, is this as good as I think it is?' And he just nodded, a solemn, knowledgable nod that seemed to say, 'Yes, it's as good as you think it is.' And of course it wasn't."

Shatner campaigned for a chance to fix the film's flaws for a special edition DVD release. "I went in to Paramount to appeal for money, $200, 000 to $400, 000, most of which I would have spent on special effects for a more exciting ending. The ending that I had originally imagined wasn't there due to lack of funds and time and whatever other political shenanigans were going on. I never actually achieved the ending that I wanted, and it's a major fault in the film. I wanted to correct it, so I went to see the people who do the DVDs, and part of my sales pitch was that they would get their money back by the number of DVDs they would sell to people interested in seeing what I wanted to do. It seems like it would sell itself, doesn't it? But I couldn't convince them. Not a frame of film has changed."

It's been eight years since he entrusted the final frontier to Patrick Stewart and the Next Generation . You wonder if he still feels proprietorial about Star Trek . "Hm. I haven't allowed myself to. There was a moment of sadness that I felt on the last movie that I made, with Patrick - I don't think anyone else saw it, or if they did, they didn't express it. I felt like a guest. And I thought well, all the pain and suffering of thirty years, and it comes to this. And yet, as an actor, I know that gigs end, and this one was ending. I suppressed the emotion, and I denied those proprietary feelings. The wheel turns."

And now, of course, the Next Generation may be making their final voyage. "I think they're probably glad about that right now."

Surely he felt short-changed by Kirk's exasperatingly lousy death scene? Being crushed by scaffolding was no way for a pop-culture icon to enter Valhalla. He should have gone saving the universe with a phaser in hand and a pair of go-go booted angels on his lap. Shatner considers this. "I rode a young horse," he begins, before grinning. "Where is he going with this? You don't know, do you? You have no idea where I'm going with this...

"I rode a young horse who reared and threw me and fell on top of me. And I went to get up, and I fell down. It's part of the denial mechanism that I have. I thought I could just walk it off, whereas in fact I'd torn a lot of muscles and I was lucky not to have broken anything. The original scenario for Kirk's death was that he would be shot in the back. I thought Kirk would fall down and then get up, and fall down again, try to get back into the action and deny that anything was happening until he was so weak that he couldn't get up, and died. So I tried that. I'd had that feeling, and I thought I could make it work, and it would be enough like the character that he would die with that struggle. I didn't think of it in grand terms, that there should be more trumpets and timpanis playing.

"And then," Shatner continues, "for the first time in any Star Trek movie I've ever been connected with, they had a reshoot. So we shot it with a little more orchestration, but not enough. But then I thought, there is a moment in dying that has never been examined on film. Cowboys die, and the heads just flop. The better people die with their eyes open, which I presume is more natural, more likely to happen, and in their last breath they communicate their lack of understanding. But I thought, wouldn't it be interesting to look at that moment when you cross the margin of life and death, and you see death coming. What would Kirk think? What would I think, at that moment when you say, 'My God, I'm dying.' And what do you see? What is that last moment that is unutterable because you can't communicate it, because you're too weak, because you're dying, because you're dead. It's that moment of wonderment.

"I'm trying to think of instances of such rapidity that you only have a glimpse of what is happening. I kayak, and when you kayak, when you flip, you flip so quickly that you can't take a breath. Your reflexes aren't fast enough, you're over so quickly. But there is a split second..." - Shatner delivers this as "Sssssssssssssssssssssss-plit, and it's impossibly Kirk - "in which you see it all going upside down, but you can't speak. And I would think that is what happens in that moment of death. You have, 'I love you!' and then you have, 'He's dead!' But inbetween, that's what happens. And I thought I could dramatise that. And I did."

A beat. Shatner chews the moment.

"But they shot in a wide shot! I thought the guy was right up close to my face!"

At 71, Shatner savours life. "I'm very much in love with my wife. I have a really extraordinarily close relationship with my children. One of my favourite things to do with the animals I am connected with - two dogs and several horses - is to talk to them, in their language. The silent language of animals. There are so many parallels with the way that animals speak to each other, inter-species. So when I focus on, say, my dog, and get inside that dog's head, I'm actually talking to the dog. I feel I'm communicating with the dog. And there have been times on the horse that I have had that zen experience of unity, that the horse is an extension of what I am, and the horse feels it, and knows that I am part of it, and we are moving together.

"And of course, my loving relationships with my wife and children are so precious to me now that they have superceded my ambition as a performer. It's that precious time that I cherish. And the time I spend away from my family interferes with those precious moments. People want my time, and that's becoming more and more valuable. And I have a ticking clock inside me, which says I'm not going to be here that long."

Mortality clearly weighs on Shatner. "I developed a script about that, called Relics , about a man who's afraid to die. I don't want to say any more about it, because the story is somewhat unique." I ask if there are parallels to his own concerns, and Shatner speaks quietly, with a sudden vulnerability. "It's a man who's afraid to die."

Surely he's prepared for cultural immortality.

"I don't even know what that means."

It means you'll live forever.

"No, I won't," counters Shatner. "Because when I die it all ends. When I die, you end. You may not exist when I die."

Perhaps he's being seriously existential. Perhaps he's being brilliantly deadpan, secretly twinkling on a sub-atomic level. Perhaps we truly are all just fragments of Shatner's imagination, figments of the omniversal Shatnermind.

"You're ending," he says, and I think he's smiling. "You go. Everybody goes."

He was Elvis, Kennedy and Kirk. He's William Shatner, and just now I don't ever want him to die.

Nick Setchfield

Nick Setchfield is the Editor-at-Large for SFX Magazine, writing features, reviews, interviews, and more for the monthly issues. However, he is also a freelance journalist and author with Titan Books. His original novels are called The War in the Dark, and The Spider Dance. He's also written a book on James Bond called Mission Statements.