How Gears of War changed the multiplayer game - and where it could go next

Gears of War's multiplayer was a watershed moment for Xbox Live. Gruesome and barbaric, yet also cool and methodical, Epic's handsome ogre of a shooter is the original “Halo killer”, knocking Halo 2 from its coveted leaderboard top spot a year ahead of the epoch-defining Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. It also very nearly didn't happen.

In the run-up to E3 2006, the game's single player campaign was just about coming together. There was still disagreement over features, with Microsoft's then-Studios boss Peter Moore expressing reservations about the family-unfriendly savagery of Gears' signature weapon, the Lancer chainsaw-rifle. But the fundamentals – a cover system based on that of cult PS2 title Kill.switch, a squad-driven campaign, an exquisitely trashed, vaguely European urban setting – were more or less in place. PvP was another matter.

Epic's previous multiplayer hits, the Unreal shooters, were all about pace and reflex, with players able to manoeuvre around each other quickly and melt away from incoming fire. Gears, however, was built for the trenches. It was sturdy and ponderous where the Unreal games were nimble and hyperactive. In developing the new game's online component, the Gears team (which encompassed a mere 20 to 30 people, at the time, led by the inimitable Cliff Bleszinski) was obliged to rethink its entire approach to multiplayer map design, and the challenge was almost too much for the project.

“We had tried making multiplayer work for a good year,” recalls Lee Perry, a former Epic gameplay and level designer who played a leading role in the creation of all three original Gears titles. “And honestly we thought the whole concept was dead and buried. We made so many test maps that played like Counter-Strike, Unreal Tournament and so on. All the old ‘rules’ for great multiplayer maps turned out to be straight-up cancer for a cover-based shooter.”

It looked like the end of the road. But at the eleventh hour, Epic's weary staffers pulled off a miraculous comeback. “It was literally one week before E3 and we were going to launch that holiday. Multiplayer was getting cut. But we had one final playtest and tried out a [prototype] named 'DM-Traffic'. We abandoned nearly everything we thought we knew about map flow and hiding spots, threw down an assload of low cover, and kept visibility open and clear.”

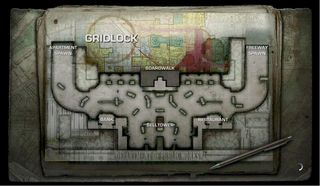

The map in question would go onto become the legendary Gridlock - a rough crescent with a spawn area at each prong, small defensible areas up staircases around the middle, and clusters of derelict cars to cower behind. “It emphasized cover-based movement like nothing we had tried before,” says Perry. “And it literally changed everything.

“If someone tried to get behind you and shoot you point-blank in the ass, you had a chance to see that coming. There weren’t endless chains of rooms and corridors – instead, there was 'a front'. You saw your enemies, you tried to suppress them, you saw their tactics unfold. It became about more than just sprinting around corners and hitting the trigger first.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

“[Level designers] Dave Spalinski, Demond Rogers and I beat on that map around the clock for a week, and we showed off multiplayer at E3. We were scared beyond belief that we only had one or two game modes while games like Halo had like 10. But people loved our simplicity and focus. Multiplayer basically went from a smoking pile of rubble to final form in a couple months before launch. So, yeah, Gridlock. Pretty cool little map.”

Gears of War's multiplayer delighted players from the off, and proved hugely influential – even first-person offerings such as Sony's Killzone 2 took inspiration from the game. It wasn't just that the cover system was so unusual in itself – the zoomed-in 'war reporter' camera, the gruelling length of the average firefight, and the sheer fact of being able to see your character's face while locked to a surface brought players closer to characters in ways most shooters simply couldn't rival. This represented no small advantage back in 2006, when HD gaming on console was still in its infancy.

“Think about how in many shooters from back then you’re zoomed way in on people, and shooting at just a handful of pixels,” says Perry. “We never wanted to ‘pixel hunt’. But we had these awesome, detailed characters we wanted to show off, we wanted big, bold characters on the screen. And you could only do that by bringing combat distances in far closer than what they had been.”

“At that point you’re having a real shootout with an enemy who is close enough to threaten you, and you can really see the danger and hit reactions. We could tighten up the field of view, abandon Unreal Tournament-style 40mph running speeds, and generally make it all so much more intimate. Ray Davis was the programmer who built out that first system, and it was one of those things where it started coming online, and people were smitten with it immediately.”

The multiplayer wasn't without its rough spots, of course. The game's most divisive feature proved to be not the Lancer rifle, as Peter Moore had feared, but the infamous Gnasher, dark god of shotguns – an apocalyptic toy that would give rise to ferocious arguments on Epic's forums. The weapon's problem, detractors contended, was that it handed an aggressive player an incredible advantage – all you had to do was somersault into close-range and fire off a blast before the victim had time to reorient. Epic would tweak the Gnasher extensively throughout the Gears trilogy, adjusting its range and power, but many of these tweaks riled as many players as they appeased.

“Without doubt, the Gnasher was the hardest thing to get right in the entire series,” Perry reflects. “It’s an incredibly complicated system. It’s easy to point at an FPS and think 'they nailed shotguns, so do what they did', but the complications came from Gears not being first-person.

“Third person cameras and close-range weaponry is just a match made in hell. There’s a crosshair in the middle of the screen - if it’s on something, you expect to hit that thing. Simple enough. But do the bullets come from the player model? Do they come from the camera? What happens when the player is behind a column, but the camera is around the corner? Can you shoot from there? What if that column is an enemy? Is that a point blank shot? Where do the bullets converge? Etcetera. It is catastrophically complex and unintuitive.

“In the hands of a good player, the Gnasher was so effective that it nullified several other systems. But it was so damn fun! Wrestling with that trade-off seems like a decade of my life in design meetings.” There were plenty of other bones of contention to pick at throughout the trilogy – grenade area of effect, for example, or the ability in Gears 3 to revive yourself from KO providing you could avoid further damage – but complaints about the Gnasher and, by extension, melee combat were “orders of magnitude more passionate than anything else”.

“We started off maybe too dismissive of some of those opinions,” Perry concedes. “But as the series continued we were more and more accepting that these were real issues for some of our truest fans.” A perpetual simmer of fan outrage is, he suggests, “the curse of a successful game. For the first one you have a ton of freedom and no expectations, you just hope people play and care about it. If it takes off, awesome! But after that, everything is sacred. Everything is someone’s favourite thing.”

Epic would make several larger innovations in the course of the series, ranging from flamboyant moves like the ability to knock back a dug-in opponent when vaulting over cover, to seismic new weapons such as Gears 3's Digger, a burrowing bomb designed to flush elusive opponents out of hiding. There were plenty, however, that didn't make the cut. “We built playable prototypes for nearly every weapon, enemy or ability,” says Perry. “That’s pretty much the bulk of what I did as gameplay designer on Gears 2 and 3. I’d say we used maybe half of the concepts that we prototyped out.

“I showed a handful of videos of these at the Game Developer Conference 2010. I can’t just dump those ideas to you - they’re Epic’s intellectual property, and many may still appear in future games. A few I demoed at GDC, though, were more cinematic dynamic camera systems for conversations that randomly happen in a map, the ability to 'perch' on tall cover walls, a 'gas leak' volumetric explosion weapon, and riding and steering Rockworms. There were some pretty huge systems planned out.”

Among the most successful features that did make the cut was the much-imitated Horde Mode – a co-op tour de force, in which players defend a map against waves of AI-controlled Locust. “Really, the thinking behind Horde was as simple as: 'many players don’t care for competitive modes, and they love co-op, but the campaign story structure can get in the way of a pure co-op play session',” says Perry. “We wanted players to be able to encounter all kinds of enemy combinations in maps that didn’t occur in multiplayer.

“We tried making custom maps with a sort of progression through different areas, and all kinds of complex, dynamic mission objectives. But it wasn’t until Matt Oelfke, a gameplay programmer, took the initiative and just dropped the creatures into existing MP maps that it just worked. It was yet another case of us over-thinking the initial design, and finding that the simpler it was, the better.”

Horde was among the earliest and most prosperous of the survival mode types that are now practically standard-issue for big budget online shooters. Bungie would pay homage to it with Halo 3: ODST's Firefight mode, while Infinity Ward followed suit with a survival playlist in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. It was another paradigm shift for Gears, tarnished only a little by the second game's woeful online performance at launch, and attracted a vast following.

When it came to Gears of War 3, Epic was able to elaborate directly on the more advanced Horde player strategies. It created a fortification system, in which cash from kills could be spent on spike strips, turrets and even deployable Silverback mechs, transforming the terrain chemistry of the map in question.

“For Gears 3 it came from noticing how people could play Horde over and over on the same maps, but holing up in different little alcoves and such,” says Perry. “We wanted to facilitate how they were already playing - trying to customize the map to allow for a ton of different tactics in each map.” Horde 2.0 appeals not least because, as with Halo's Forge level editor, it invites fans to take artistic ownership of a facet of the Gears universe, fleshing the terrain out in surprising directions.

Gears of War 2 and 3 also gave us custom weapon and character skins, unlocked by earning XP during multiplayer and the campaign. Though unremarkable on paper, these were telling concessions to the absurd popularity of Call of Duty's multiplayer levelling system, which had given rise to an industry-wide obsession with grinding for equipment (a taste for tat that would prove convenient when console publishers began to dabble extensively with the idea of selling in-game items separately).

So why didn't Epic go the whole hog, and build in a full suite of non-cosmetic unlocks? “We were playing Modern Warfare just like everyone else,” recalls Perry. “And marvelling at how incredibly well they blended an almost RPG-like skill tree to the MP competitive shooter arena. It really came down to playing to our strengths and using our manpower wisely.

“A game like Call of Duty has more people working full time on their menus alone than we had working on our core gameplay team. Systems like Halo’s web integration, and quantity of game modes… yeah, they’re amazing accomplishments, but at the time we just preferred to keep the team small and be the agile little guys in the arena.”

Some would argue – including this writer – that progression trees don't belong in a shooter that achieves so much by placing opponents on an even footing initially, in which the most devastating weapons must be collected from the maps, rather than selected on the menus. Perry disagrees. “I think systems like those can totally work for Gears if the people making the future games prioritise them. It all comes down to whether you allocate energy to a great single and co-op campaign, or to competitive multiplayer, though. That balance will always be a tough one, and highly debatable.”

While much declined following the third game – not helped, it must be said, by the entertaining but underwhelming spin-off Gears of War: Judgment – Gears of War is no longer the “little guy in the arena”. New developer the Coalition has formidable resources to draw upon – as of July 2015 it had around 200 developers on the books, including Epic's former director of production Rod Fergusson. But will the series ever reclaim that Xbox Live top spot? What can it do to head off today's crop of MOBA derivatives and high falutin' parkour shooters, to say nothing of doughty old foes like Halo and Call of Duty?

“I would say very broadly that it needs to continue going its own way, and remember how many successes we had when we remember the value of simplicity and personality,” comments Perry. “Trying to compare feature counts with competitors and following the crowd isn’t a great direction. But the people working on the current games know those mantras, so I have confidence they’re going to do really well with it.”

“There is a constant battle between pleasing your hardcore existing fans and trying to attract new players to build out your player base,” he concludes. “I’ll be really curious as to which trade-offs are made for those goals, and which new features can play to both camps.”