Gaming's most fiendish anti-piracy tricks

Assassin's Creed II could learn a thing or two from these

Publishers have struck back will all kinds of increasingly controversial copy protection systems over the years, the PC version of Assassin’s CreedII currently the latest title to raise the ire of gamers with its “No ‘net connection, no game for you” policy. But that kind of thing is no fun. We remember when publishers and devs used to come up will all kinds of crazy and imaginative ways to keep us off the pirate ship. And thusly, we’ve looked back in time and picked out our favourites. And thusly, here they are.

Lenslok

Used in: A whole bunch of ‘80s home computer games

How it worked: Once the cacophonic banshee-wailing of the tape loading sequence finally came to a merciful end, the game would compound the player’s emotional trauma by flashing up a garbled two-letter code on screen.

Above: Gaming in the '80s was seriously rock 'n' roll

The code could only be properly read by putting an included plastic prism lens up against the screen, and once deciphered it had to be typed in to make the game run. But there were two problems. Firstly, the code had to be manually scaled to make it readable on different sizes of TV, and the system didn’t work at all on particularly big or small screens. Secondly, the codes were incredibly easy to hack, given a bit of coding knowledge. Needless to say, it was dropped after much complaint.

Gimped Batman

Used in: Batman: Arkham Asylum

How it worked: Very sneakily indeed. Rather than simply blocking pirates from playing the game, Rocksteady chose to give them just enough tantalising bat-joy to show them what they were missing. Illegal copies of the game worked perfectly apart from one little detail. Batman’s cape glide ability was disabled, making the game playable but uncompleteable. If the Joker made DRM, this is the DRM he would make.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

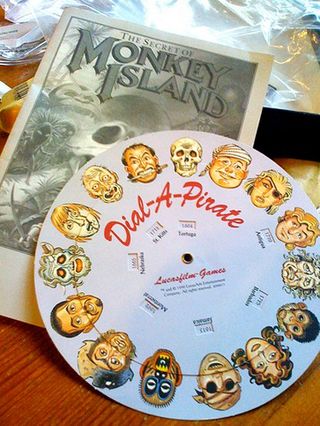

Dial-A-Pirate

Used in: The Secret of Monkey Island

How it worked: Disappointingly, not by delivering a hot, oven fresh pirate to your door. The game shipped with a cardboard dial, comprising two circles of different size set one inside the other. Each disc was printed with one half of a series of pirate faces. The game displayed the face of a particular pirate on screen, and the player had to turn the middle disc in order to line up faces and identify the year the pirate was hanged. Typing in the date allowed the game to run.

All your base are belong to EA

Used in: Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2

How it worked: By asploding the pirates’ dreams of free RTS in a very real sense. After 30 seconds of play on a pirated copy of the game, the player’s base and units would detonate. Whether the cause was suicidal pirate guilt or an overzealous bid on the units’ part to escape the horror of war is unknown. What is known is that like more recent EA DRM, the base blasting trick caused all kinds of problems, in particular blowing up the armies of plenty of legitimate players. Call it a pre-emptive strike just in case they were thinking of passing a copy on.

Most Popular