BioShock Infinite “may not have been the thing I wanted, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it wasn’t the thing the audience wanted”: Ken Levine guides us through his entire gameography

Edge: The Collected Works | From immersive-sim innovation, through undersea peril, and onto new beginnings back out in space, Ken Levine talks through his impressive and iconic gaming portfolio in his own words

Ken Levine's work is defined by a wariness of the human animal and its capacity for cruelty. Yet he sees himself as "deep down, a real optimist". Were it not for a stubborn, self-deceptive streak of hope, he would have given up on Irrational Games a decade before making BioShock. "Maybe Irrational and Ghost Story are the one world where it worked," he says of the studios he's co-founded. "But I always had my eye on that world. And to some degree, you have to lie to yourself and kid yourself."

By the time Levine joined the videogame industry, he had already lived the highs and lows of a career screenwriter. "I was getting flown out to Hollywood when I was 19 years old from college, and I was like, 'OK, I've nailed it, I've made it'," he says. "And then it didn't work. I had to go through a period of my 20s where I was recovering from failure and picking myself back up again. But the fact that I had been through that prepared me for the games industry, in that I expected to fail a lot, and maybe fail completely."

He remains amazed that the studio behind Ultima Underworld and System Shock hired him for his first job in games. "Because one could have thought, given the age of the industry, that I was washed up," he says. "At 29, I was older than most people at Looking Glass."

When Levine left Looking Glass Studios to found Irrational Games with colleagues Jon Chey and Rob Fermier, failure met them immediately. "We lost our first project, right at the beginning," Levine says. "I had not shipped a title, Thief wasn't out yet, I had no money."

Levine found himself flying out to California to pitch a "weird strategy game", with little but a barely functional demo to show and an interior voice telling him he was screwed. "But then

I said to myself, 'OK, what if I just keep going, and assume in my head it's gonna work? Most people would quit at this point, because most people are rational. But what if I don't quit? What if I just suck up the pain and keep going, and continue being embarrassed in these meetings?'"

The company did indeed keep going, until eventually a call came from Looking Glass: Irrational would make System Shock 2. "And to the team's credit," Levine says, "we really put our heart and soul into demonstrating that we were worth something."

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Thief: The Dark Project

Developer: Looking Glass Studios / Publisher Eidos Interactive / Format: PC / Release: 1998

On Thief, I had this great lesson, coming up with six or seven different ideas for what that game could be – writing ten-page documents and getting concept art made for these totally disparate games. One was called Better Red Than Undead, one was called Dark Elves Must Die; Split Knuckle was a kung-fu game. We had all these crazy ideas. It was an amazing time, and Looking Glass was an amazing place, but I also got that immediate lesson of: 'Your ideas are gonna get thrown out a lot. You're gonna have to invest a lot of time and energy in things which are going to go nowhere'.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

My mentor was Doug Church, one of the key guys behind Ultima Underworld and System Shock, probably the father of the immersive sim space. When he knocked my ideas back, I respected him enough that I assumed he had a good reason, and I think he did. Eventually, the idea came from the head of Looking Glass, Paul Neurath, who just said, "What if it was a game about a thief?" It lined up with a lot of what we were doing in terms of the awareness cycle of enemies. The traditional thing at that time was that your enemies would either see you or not see you – there was none of this 'if' system. And that was quite innovative. That was the idea that stayed.

I came up with the Trickster and the church of the Hammers. I didn't come up with the middle group, the Keepers, so I don't want to take credit for that. I was getting my head around the conflict of this nature-loving, Dionysian-style Trickster character, which is taken from literature and mythology, and the church – which is trying to modernise everything and fighting against these paganistic forces. But they were both extremes.

If you could define it, the theme of my storytelling is 'be wary'. I don't know how to build a world without those themes, because they're so present. You have political ideologies that range across different outlooks, but you wonder if the extremes are more like each other than they are different from each other. Because they tend to adopt a lot of similar practices, the us-versus-them thinking – a Manichaean view of the universe. It happens a lot, and it often leads to dehumanisation and bad outcomes. Whether it's Hitler or Mao, rigidity leads to death. I like exploring that notion, because I just find it endlessly fascinating. And it does endlessly repeat historically, over and over.

System Shock 2

Developer: Irrational Games, Looking Glass Studios / Publisher: Electronic Arts / Format: PC / Release: 1999

I had enough business experience that I could smell the smoke of the financial troubles at Looking Glass. I'm so grateful to have gone to a place where there was such a focus on mentorship and learning. It was an amazing company, but they struggled to be financially stable.

I had two partners who are very, very smart – Jon Chey and Rob Fermier, my Irrational co-founders. We lost our first project three weeks into it. We had no money, no investors, and we had to scramble. But that turned out to be a good thing, because a couple of months later we got System Shock 2.

It was a very lightly funded project. It was hopes and dreams and a little bit of money. I'm still amazed how quickly it was done, given the Judas time period. Nobody had really done a firstperson shooter RPG hybrid. Once we figured out the formula, that immediately helped us understand what the game was and what we could do differently than what we had seen before.

I was extremely taken with System Shock 1, which I just played as a gamer before I got in the industry. The interface was extremely non-standard; there was no mouselook. We tried to keep what we loved about it, and then modernise what was getting in the way of the experience. The gift I got was from audio logs and SHODAN and this naturalistic tonality – of humans in a really bad situation.

You can go back and look at System Shock 2 and, honestly, if you're not a nerd, you probably wouldn't even know what you're looking at. But the audio voice was 100 per cent accurate. And I was like, 'If we can lean into that, we can ground this really weird-looking game in truth and humans, in a way we couldn't do before'. So that was incredibly powerful.

The Lost

Developer: Irrational Games / Publisher: Crave Entertainment / Format: PS2, Xbox / Release: Unreleased

It was a very tough project. We got involved with a publisher called Crave – they were well-funded, and they were excited about us. They started a second project with us, which became Freedom Force.

The Lost was the first console game we tried to do. It was a thirdperson action game, with a really grounded, interesting story adapted from Dante, where this woman, Amanda, loses her daughter. The Devil appears for her at a moment where she's on a bridge contemplating suicide because she's so depressed. And he says, "You can go down to hell and try to get her, but if you fail, you're gonna stay there." People really liked the story.

We struggled technologically to get that thing working on the PS2, which was a very strange beast. My partners had left the company after System Shock 2 – Jon to go back to Australia, where he's from, and Rob to Ensemble. Jon eventually came back. But I did not have the experience to understand the technological challenge. We kissed a lot of frogs along the way. We went through the LithTech engine and the Unreal Engine, and neither one of them were really up to the PS2.

Eventually the publisher ran into financial problems, and they started putting the squeeze on us. The money started drying up, and we finished the game in great conflict in terms of getting paid. I was trying to make payroll, and it was the least fun time in my life. I didn't think the game was of good enough quality to put out and we basically ate it, because

I didn't want it to damage the reputation of the organisation. That's not a function of the people working on the game, it was a function of limited time within budget and some technological challenges. It was the lowest period in my career, working on a game for that many years and then deciding not to ship it because it wasn't up to our standards.

Freedom Force

Developer: Irrational Games / Publisher: Crave Entertainment, Electronic Arts / Format: PC / Release: 2002

Because Crave got into financial trouble, Freedom Force got shuttled off to EA's distribution division, EA Partners, which they set up for when they had spare marketing resources. The problem is they didn't promote those games, because they made less money off that. That's understandable, but it was not good for Freedom Force. That was very disappointing.

We put a lot of heart into it. It did better than our other games, and it was a real morale boost that we had put out a product as Irrational after System Shock 2. Jon had come back and had set up Irrational Australia, so we were one company with two studios. Most of Freedom Force was done in Australia, and we did the story and the sound here in the US. That was a good experience.

It was a love letter to Silver Age comics, the early Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko stuff. If you go back and read Iron Man's origin story in the comics, it's in Vietnam and he basically fights this Viet Cong villain, and it's very much on-the-nose – the view of the world of at least one segment of the American populace, which was anti-communist. The dialogue and attitudes are very much of their time. But the Marvel stuff worked so well because it was so rooted in character, even though it was very exaggerated and cartoonish. Peter Parker and the great Uncle Ben story, it's a fable. Parker learns responsibility. They're all morality plays. That's why they still resonate. I wanted to take that notion, as well as the art style.

At the time, there was this whole meme that you couldn't do a superhero videogame – they were 'cursed'. We actually heard that from journalists and publishers. I don't believe in curses, and I just kind of ignored it. We showed it could be done, and then Arkham came in. I think those guys similarly understood that the combat and the punching and the superpowers are all fine, but that's not the operating principle of superheroes. What makes a hero is sacrifice and a moral framework to work in.

Tribes: Vengeance

Developer: Irrational Games / Publisher: Sierra Entertainment / Format: PC / Release: 2004

Vivendi came to us and we needed a job at that point, because The Lost was kind of a disaster. Freedom Force did well, but not enough to make us any royalties. Publishing deals were garbage back then – the developer almost never made money. Tribes didn't seem like our thing, but Vivendi thought there was an opportunity to grow the audience by having both the multiplayer and a singleplayer story campaign.

The part of me that knew the company needed a job was like, 'Yes, let's do this'. Then, when I got to the IP, I struggled to figure out how to tell a story about it. Because it wasn't designed to be a narrative, it was designed to be a background for this arena, with a really dedicated core fanbase. I felt a little bit lost on that.

Looking back, it probably wasn't the wisest thing for me to take on as a writer. In fact, I got fired from that gig by the publisher, and they brought in two Hollywood guys. Then they fired them, and they brought me back to finish it in very limited time. I had to rewrite it and get it recorded in a studio in California. I don't think from a narrative standpoint it was our most successful experiment, but I learned something from it. And it was fun to get fired again.

SWAT 4

Developer: Irrational Games / Publisher: Sierra Entertainment / Format: PC / Release: 2005

Rainbow Six was very powerful. Even though it's not a horror game, you're so nervous because one bullet could take you out. We liked the tension that was just natural in a SWAT game. There's no minigun or BFG. You're encouraged to go light, but the enemies have no such constraints on them.

I think, pound for pound, SWAT 4 was one of our best products, in terms of the amount of time it took versus what we got out of it. It was a relatively short development cycle, and the team really pulled together. Because I was mostly distracted, my primary contributions were helping establish the vibe of it. Originally, it was more corridors and office buildings.

We did far better storytelling than Tribes: Vengeance in that game with far less. It was a really good training ground for the environmental storytelling we were to do on BioShock. We were like, 'We don't really have any words – how do we tell a story?' The tools had come along a little bit since System Shock 2. In the Unreal Engine at that point you could get some reasonable-looking spaces that looked relatively organic, whether it was a dingy bodega, a dingy hospital, or a dingy serial killer's house. Everything was dingy in the game by design.

I liked the idea of entering an emotionally dark space and then having to try and make something come out of it that wasn't terrible. I think that was quite successful, and the team did a great job pulling that together. The gameplay was good. We improved on SWAT 3.

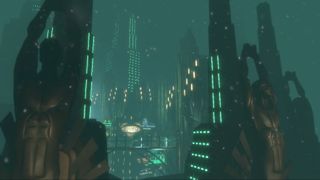

BioShock

Developer/publisher: 2K (2K Boston, 2K Australia) / Format: 360, PC, PS3 / Release: 2007

"Up to BioShock, I wrote almost all of the words in the games that I worked on."

The creative director is the guy who has to decide what goes in the game and what doesn't. That's the primary job. The job is also to keep everybody on the same page, so we all know what we're building. That's the hardest part of the job, but it's also the most necessary part of the job.

Up to BioShock, I wrote almost all of the words in the games that I worked on. Now, I have a lot of help from a writing team, but it's still, at the end of the day, my responsibility to decide what goes in the box. And that thing has to be coherent. I believe it's a real role. Somebody has to have the final say. I also think that you have to be involved in everything.

Everything we do in game development is storytelling, from programming to office administration. We all share the same common goal, which is we're telling the story to the user. That story sometimes exists in gameplay, sometimes in audio logs, sometimes in the visual space, but it's always a story.

To really be a creative director you've got to have your paws in every single thing. And you also have to know when to shut the hell up, because you're surrounded by people who get what's going on, and they're way smarter on the topic and have way more experience. And you need to be careful not to micromanage. But if you don't have some degree of micromanagement, then you don't have a consistent vision. So – world's smallest violin – it's a tough job. But it's also an amazing job.

Many of the people on the BioShock team came to the company because they liked System Shock 2, and were like, "Why are we not making one of those games?" And I was saying, "We can't make those games because they don't sell, and I don't want the company to go out of business." Finally, they wore me down. We came up with something, made a cheap prototype, took it out and pitched it.

Everybody said what I expected: "We love System Shock 2, this looks really cool, but it doesn't make any money – sorry." And it was frustrating. It was a bunch of years we were working on it, going back and forth. We tried this, we tried that, and finally we came up with this idea of pitching to the journalists instead of the publishers. We were led to a guy at GameSpot, Andrew Park. He was kind enough to write a retrospective on System Shock 2, and I said, "What if we threw this into the article?"

The next day, people saw the article, and we started getting phone calls. I think it created a sense of demand in the publisher. Very quickly after that, the game was set up. Originally, we were signed up with a very modest budget, but then, through a chain of events, Take-Two ended up buying us, and because they owned us, they put a bunch more money into BioShock. It was still an extremely cheap game by today's standards for triple-A, but we got enough money to express what we were trying to express.

BioShock was the first time I felt that I could express on the screen the aesthetic I had in my head. I felt the emotion of it. I would be at the office at two or three in the morning sometimes, working on it, and I remember just being vibed out by the feeling of the game and the music.

I was born in New York, I grew up around it, and BioShock was very much my strange version of a love letter to New York. It's about immigrants and refugees from the first half of the 20th century, and I grew up around those people, whose first language was Yiddish, and who either fled Germany or Eastern Europe. And it was the music of my father's youth. I talked to him and I said, "What were the songs, Dad?" I had read a ton of history too, and that was the first game I really got to put in a historical era.

I loved working on BioShock. It did almost get cancelled, though, right before the end. It was going over budget and over time. They had no way of knowing that it was going to be a big thing, and it's so weird, that game, you know? The whole infanticide angle of it, where you're killing these Little Sisters. The publisher was very nervous about that, understandably. We had a great guy on the team on the publishing side, who defended that principle and kept it in the game. It was experimental, but it was exactly the game I wanted to make.

BioShock Infinite

Developer: Irrational Games / Publisher: 2K / Format: 360, PC, PS3 / Release: 2013

We were doing an XCOM firstperson shooter game at the time, which was interesting. We were struggling to get our head around the squad control. I just never thought that was going to be a big game, because it's so clumsy to do in firstperson. I didn't have a great solution to fix it. The publisher wanted us to do that game and BioShock 2 in a relatively short period of time, and I talked to the head of the publishing group and said, "I don't think we can do that and make a good game." And his response was like, "Well, then somebody else will." After some complicated conversations, we ended up doing the next one after BioShock 2. Because I didn't want to go back to Rapture – I didn't have an idea for it.

I wanted to do something different, but the same. There are a lot of similar themes – an American story from an alternate past. But with every game we also tried to take on a new challenge. I have always cared about character in games, and on Infinite I wanted to go further with the companion character, Elizabeth, and really develop a relationship with an NPC in a way that nobody had quite done before. That was the technological challenge of that game.

It scaled to the point where I was struggling to keep everybody on the same page. I was pushing for a more action-oriented game, but the way the game worked was actually quite different from BioShock. We'd always had this notion from Thief of enemies becoming aware of you, and heating up and cooling down based on vision cones and proximity, whereas in a Call Of Duty game you go over an invisible tripwire, and that alerts all the enemies and sets up the scripting and everything like that.

Infinite was built more that way in terms of the combat, so all the tools we had developed, such as traps, didn't play well with the way the game was built. That got away from me. I'm sure there were really good reasons, because we had all the Sky-Lines and stuff that complexified that, but systemically that game drifted from what I wanted. I'll put the blame on me for that, because that's the job of the creative director. But I was just overwhelmed by the scale of the thing.

"Some people love the gameplay and prefer it to BioShock."

The Sky-Lines were me trying to do something action- and movement-oriented, which we hadn't done before. We're normally moving at a snail's pace, relatively, through an interior environment; then we're making a game where you're flinging around in the stratosphere. It was a big adjustment for us. The problem was that the Sky-Lines were so expensive to build that we couldn't build enough space to support the feature. The team did a great job of bringing that feature to life – there was just not enough of it in the game for it to really land.

If we had done a sequel to Infinite, I think I would have spent more time on that. That thing was built on Unreal Engine 3, which is not an outdoor engine. Sky-Lines were a lot of spit and chewing gum and prayers. Players would be surprised how much of games are put together with spit and chewing gum – even the best ones that have worked really well.

I really focused my energy on the relationship between Booker and Elizabeth, telling that story, and then the thematic elements of the world. What is the philosophical impact of a world where the many-worlds theory of quantum mechanics exists? As Richard Feynman once said, if you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don't understand quantum mechanics. As a drama major, I was not the guy who was really going to understand quantum mechanics, but I understood it conceptually enough to turn it into a narrative, and I think that worked pretty well. In terms of endings, I think it was the best one we've ever done. It was the first time I've ever been really happy with an ending of a game I've worked on.

Our team really delivered, and the actors really delivered. I think the gameplay suffered a little bit. It's funny, because some people love the gameplay and prefer it to BioShock, but with the types of games I like to play, it didn't land as much. And that's a function of me being a little overwhelmed in the role of the creative director, and not being able to line up everybody to the same message. But it actually turned out for the best, because people seem to like that a lot. It may not have been the thing I wanted, but that doesn't necessarily mean it wasn't the thing the audience wanted.

Judas

Developer/publisher: Ghost Story Games / Format: PC, PS5, Xbox Series / Release: 2025

"The closure of Irrational was complicated."

The closure of Irrational was complicated. I felt out of my depth in the role. You're this creative person, and all of a sudden, as your vision increases of what you want to do, you have to become a manager, in a way that you don't necessarily have any training or skill in. My mental health was a mess during Infinite. I was stressed out, a lot of personal things were going on in my life at the time, and then my parents both died. I just couldn't do it any more, and I didn't think I had the team's confidence.

So my intention was to go and say, "Look, I just need to go start a new thing, and Irrational should continue." That's why I didn't maintain the name Irrational. I thought they were going to continue. But it wasn't my company – I sold the company, so I worked for Take-Two, and the studio was theirs.

The decision was made at a corporate level that they didn't think they should continue with the studio as a going concern. My feeling was that it probably would have made sense. Take-Two did a BioShock remaster – that would have been a good title for Irrational to get their head around, build a new creative director structure, and then build off of that once they had the confidence to do the next BioShock game. I don't think I was in any state to be a good leader for the team.

I had a lot of respect for the people on the team. Once we found out that the company didn't want to keep going, we tried to make that transition the least painful layoff we could possibly do. We had multiple job fairs for the team, we allowed them to stay in the studio, we gave them generous transition packages, we fed them. That's not to say that didn't suck. But I don't think I could have been their leader any more, and I knew the next thing I was going to do was going to have a very long period of R&D. The problem is – and you see this problem with big studios – what do you do with 300 people when you're going to have a multiple-year R&D project?

Interestingly, a good chunk of those guys ended up coming back and working on the new BioShock game. Then a bunch of them went and started their own companies. At Ghost Story we work with a whole bunch of companies that were founded after the closure of Irrational. I'm proud to say that, despite the negativity of that situation, there were a lot of young entrepreneurs that were just ready to go do their thing. I think it worked out for the best in the long run, but it was painful in the short term.

In Judas, we wanted to make a game where you, like in System Shock, were the proximate cause of the problem. The ship is broken, and you broke it. You broke it for pretty good reasons, but was your reaction an overreaction? The character's got this debt already, a burden, but it's not because she's a villain. You understand why she did it, but the effect of it has a lot of unintended consequences that now she has to live with.

There's this Manichaean notion that there are angels and devils in the world, and that's not been my experience. I rarely met a devil who doesn't have a bit of an angel in them, and vice versa. I don't like simplistic heroes and villains, because I've never met one. I like these broken characters because I relate to them.

As a BioShock fan, Judas' promise of influencing the story and characters sound amazing – but what will that look like at launch? Want to play with enemy NPCs? We've got the best stealth games for you to take a look at! Thinking of Rapture? We're also playing close attention to all things BioShock 4.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.

Diablo creator rips into modern ARPGs for being all about "killing screen-fulls of things instantly," says Diablo 2's pacing "is great" and "that’s one of the reasons it’s endured"

Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2 dev says the original RPG attracted an audience "sort of like Euro Truck Simulator," with "quite a lot of people who never play games"

Most Popular