Games need to drop Hollywood's reality and start telling their own, better stories

Games have immense potential as an art form. That should be obvious now. The industry has an increasingly impressive pool of talent in all creative fields. Gaming as a medium possesses all the tools available to art, music, literature, radio and film, and has the interactive element to boot. There's theoretically absolutely nothing that games can't do, and we've seen some pretty exciting creative ripples come from that capability throughout this generation.

But at the same time, a huge amount of that potential remains simply potential. It feels like games are still holding back from unleashing what they can really achieve as their own medium. Because in a great many ways, games aren't yet performing as their own medium. They're hamstringing their own creativity by taking too much of the wrong kind of inspiration from film.

Take game worlds as an initial example. They're often visually stunning, but very rarely do they feel new or original. And I'm not talking about subscription to fashionable me-too trends in game design here.

No, the actual problem is that, irrespective of inter-game borrowings, the whole framework that game worlds and stories operate within has been borrowed from another medium entirely. Modern games, particularly those of a triple-A persuasion, frequently purport realism and believable, human characters, but they fail because they don’t look to the real world for their inspirations. They don’t even look to the likes of literature. They always go straight to movies, and as a result they only ever emulate movie reality. And movie reality is a place that exists a long, long way from the real real world.

Just as artificially flavoured fruit sweets, yogurts, ice cream and the like taste absolutely nothing like the soft, pulpy real-world inspirations sketched cartoonishly on the packaging, yet are interpreted by our brains as being strawberry or banana flavoured through years of conditioning, so too do we accept movie reality--within context--as being a real place. It’s a place distant and parallel to the real world, and operating on its own internal rules, admittedly, but we accept those rules and don’t question the way they work, however objectively ridiculous they might be. When a cinematic car bumps into a wall and inexplicably explodes on contact, we accept that the flames taste of watermelon.

And for whatever reason--perhaps the medium’s evolution in the hands of a generation brought up in Hollywood blockbuster boom period of the ‘70s and ‘80s, perhaps just laziness of research--video games have reached blindly into that grab-bag of visually impressive, easily digestible nonsense for years, accepting every ludicrous trope and coolly justified untruth and lending them further weight and credence by the implicit condonation of repetition.

Typifying case: The exploding barrel. It doesn’t work. In real life, if you shoot a barrel full of fuel, you lose all your fuel as it leaks out onto the floor. Simple as that. But in movie-land, gasoline is apparently so unstable that driving a car over a pothole should cause the apocalypse (provided the context plays to the hero’s benefit). And so the exploding barrel has become the absolute king of video game design tropes. Even though it’s a load of bollocks.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

That’s a simple, blunt example to sum up the situation, but the problem goes much deeper than unrealistic combustion physics. It affects both the quality of script writing and the very fabric of game worlds. In terms of the latter issue, it leads to far too many settings which, while often incredibly visually impressive thanks to the talent of the production designers currently working in the triple-A industry, all too frequently feel all too familiar. When games were a new medium, the novelty of playing a level that was “just like that bit in Aliens” or looked “just like Blade Runner” was an exciting point of recommendation. But now? Cinematic visual language has invaded games so completely that there are few surprises around.

Post-apocalyptic games are nearly always Mad Max 2. Sci-fi games? It’s Ridley Scott, James Cameron and Star Wars all the way. Horror game? Throw together a few Romero films, a bit of The Thing, a fat slab of HR Giger, and away you go. And it gets worse when you look at the kind of writing that games still largely harbour.

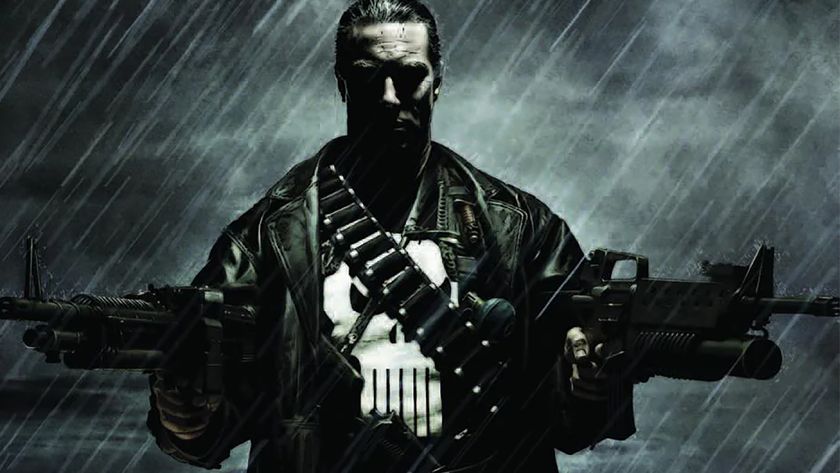

We frequently bemoan gaming’s two-dimensional characters and generic big-balls action-bastard dialogue, but I can’t help but wonder how much of that problem is a product of the ability of the games’ writers and how much of it stems from a desire to emulate the snappy, one-liner driven vibe of Hollywood action movies. The framework of blockbuster cinema seems also to have become the de facto approach to creating video game narrative, in both characterisation and the types of stories that are told.

Through the many possibilities afforded by interactive storytelling and the ability to ‘be’ the protagonist (or even manipulate an entire ensemble cast), games have almost limitless potential for deep, nuanced, intelligent, mature storytelling. But by shackling themselves to the conventions of the most shallow subset of a mechanically very different medium, they’re hamstringing themselves every hobbled step of the way.

I’m not saying that all triple-A games are awful Michael Bay affairs, of course. The Last of Us, although aping the visual style and tone of No Country for Old Men and The Road, has excellent, multi-faceted, desperately human characterisation that it augments fantastically through interactive subtext. The BioShock series, despite various granular failings, provides fresh worlds and big, challenging ideas that a Hollywood blockbuster would rarely risk the budget required to combine.

But why don’t horror games yet have their equivalent of the World War Z novel? Why are crime games still stuck in the mould of Scarface, Tarantino and Bad Boys when there are much more human, affecting stories to be told in those worlds? Why are our huge, intricately constructed open-worlds designed primarily for fucking about and smashing shit up, emphasising their video gaminess rather than augmenting a grounded, tactile sense of reality?

Why, with grim contemporary military conflicts resonating through the cultural consciousness, and multitudinous first-hand accounts available, do gaming’s self-confessed attempts to maturely relate them still come out like a sandy version of Commando? And why is the admittedly likable Nathan Drake vaunted as one of our best-written action heroes, when he’s actually just a container for pithy comebacks and put-downs, wrapped in the portmanteau aesthetic of several existing cinematic heroes and redeemed by a talented and charismatic voice actor?

The answer to all of those questions is the same. Gaming is too in thrall of Hollywood. And it needs to stop that silliness. We have the talent, the tools, and the developing narrative language to make much more than unlicensed adaptations of another medium’s big hits. Given what games are capable of, we’re drawing from a detrimentally small pool of inspiration. It’s like having a TARDIS and only using it to see what the neighbours next door are watching on TV. Let’s start looking a bit further afield, shall we?

You know that kid at parties who talks too much? Drink in hand, way too enthusiastic, ponderously well-educated in topics no one in their right mind should know about? Loud? Well, that kid’s occasionally us. GR Editorials is a semi-regular feature where we share our informed insights on the news at hand. Sharp, funny, and finger-on-the-pulse, it’s the information you need to know even when you don’t know you need it.