Small choices are huge in Firewatch, Oxenfree and the new gaming breed

[Note: Some spoilers regarding the nature of Firewatch and its opening are below.]

You flip through the opening moments of Firewatch, a new first-person thriller from developer Campo Santo, like you’re speed-reading through someone’s biography. Without so much as a photograph in mind you spend just a few minutes learning about Henry, the man you’re about to play as a fire lookout in a Wyoming forest. You interject only at key moments as a god-like guest author, chiming in on important subjects like how Henry deals with an attempted mugging, and what kind of dog he gets with his wife, Julia.

If these choices strike you as weightless and insignificant, it’s probably because you’re peering at them through the lens of video games - some telescope on a far-off planet pointed back here at our teensy little decisions on Earth. Epic games have made galactic commodities of choices, planting them in the road like neon signs that can be seen from space. Go left to make it rain prozac-infused puppies, go right for the reign of eternal eldritch horror from which none shall ever escape. The outcomes have gotten so big, divergent, extravagant and in-your-face that a singular endpoint in a game claiming to be about choice is seen as a betrayal, even if a billion permutations precede it. Players have been trained to wait and look for the outlines to appear, blind to the coloring inside.

Without diminishing the work done by the big story pioneers like BioWare and Telltale, you have to wonder what’s important when everything’s important. When every choice is between who lives and who dies on which far-off planet, your pick of a pooch seems trivial. But we know it’s anything but, and ruthlessly divorced from the way a game bleeps assuredly after an epic decision has been made and logged - whether you electrocute the citizens of InFamous, or choose to abandon someone in Until Dawn’s kitsch teen kill ‘em up. It devalues the small decisions that are not only more representative of real life, but are genuinely difficult. You try agreeing on a dog breed with your significant other in the space of a few minutes and let me know how it goes.

Unconventional games like Oxenfree, Tharsis, Firewatch and even Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain (which you’d be tempted to discount for its big-budget nature) are embracing smaller player-driven decisions and, in a sign of unexpected confidence, don’t even make a big deal about it. They’re novelistic, human and thoughtful, letting a person sink into the character they play, either by letting them solidify bits of a fictional history, or letting them choose how the protagonist behaves in front of others. They are ironically confident as video games, hinging on your input and subtly modifying the scene without announcing the work being done IN THIS HERE VIDEO GAME.

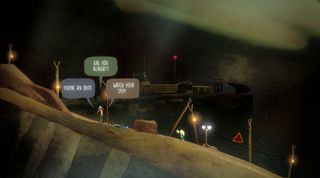

In Oxenfree, you co-inhabit the head of Alex, a teenage girl marooned in mystery on an eerie, antique island - seemingly one state over from Twin Peaks. The elegant adventure is driven not only by the unsettling sounds emanating from your radio, but by the tension growing between Alex and her chatty teen friends: the new step-brother, the earnest airhead, the spiteful drama queen, etc. Oxenfree’s multiple outcomes roll out from the numerous discussions you have with them throughout the game, in which you choose totally organic responses to frame Alex as someone who is understanding, forgiving, skeptical, or spiteful. And none of those are words that just float around on the screen. Oxenfree is a game about who Alex is or could be, not what happens in the plot (although that’s pretty cool too).

Tharsis resembles a ruthless board game that runs on numbers - and the numbers are coming to kill you. As the captain of one of the most fragile and unbelievably awful, horrid, fucking awful spaceships ever made, it’s your job to get your wide-eyed crew to Mars safely through a series of jaw-clenching dice rolls. The fun is not so much about overcoming the odds (because you won’t) so much as finding best practices in the face of imminent catastrophe. Your zero-gravity, zero-luck astronauts can’t roll the dice to progress without food between turns, so a choice may exhibit as such: Do we eat the medic? Is it ok if she was dead anyway? Is it ok to KILL her if it means everyone else will survive?

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The teens of Oxenfree will almost certainly make it to the end of the story in some fashion, and the astronauts of Tharsis almost certainly won’t. The dearth of trumpeted outcomes in these games makes dark, moral conundrum no less interesting, though, and no less relevant. There’s been much talk of Metal Gear Solid 5’s ending - the true version, the secret version, the unfinished version - but little on how you could enter its war with a moral objective. Straining yourself and your patience to ensure non-lethal outcomes, or to painstakingly airlift every child soldier (or not) are real choices in play. They’re recorded and scored, too, but only because they’re part of the game’s DNA.

Every time we see a pop-up for Good or Evil points, or every time we craft a route through a game to reach one of 16 different endings, we chip away at the relevance and reward of grounded, human-scale choices. Whether it’s weighing murder for the sake of survival, or sparing someone’s feelings in a tense situation, or trying to spare an enemy in war, these contemporary games are offering up deeper, more relevant choices while we’re playing. But there’s a chance we might miss them entirely, having been trained to disregard anything that doesn’t lead to an operatic endgame change. A thousand tiny choices to make a unique protagonist is seen as meaningless when they don’t end up in another universe at the end. That doesn’t seem right.

Part of this exaggeration of choice is due to the player’s typical position of power, of relying on transparency and programmed outcomes: if X, then Y, and the bigger the Y, the better the game design. Games like Firewatch and Oxenfree reflect a newfound maturity, though, finding confidence in the act of writing their characters - the fire lookout, the ship captain, the soldier and the teen - not alone, but with the player in mind. It’s the little choices that tell a true story.

Ludwig Kietzmann is a veteran video game journalist and former U.S. Editor-in-Chief for 12DOVE. Before he held that position, Ludwig worked for sites like Engadget and Joystiq, helping to craft news and feature coverage. Ludwig left journalism behind in 2016 and is now an editorial director at Assembly Media, helping to oversee editorial strategy and media relations for Xbox.