The enduring mysteries of Fantastic Four #1 (and their possible answers)

The big mysteries not even Marvel knows the answer to about 1961's Fantastic Four #1

It's the big bang of the Marvel Universe.

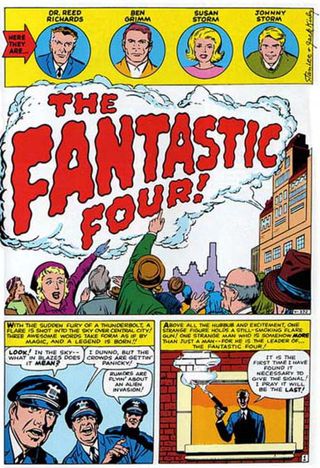

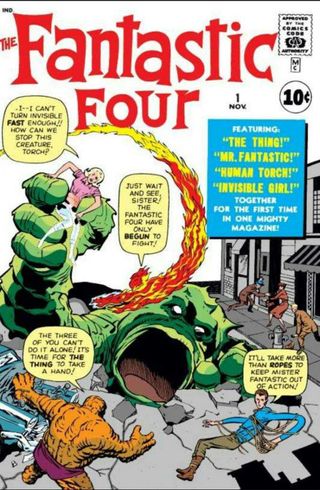

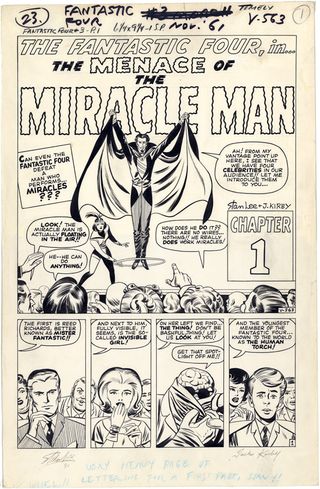

Fantastic Four #1 was released on August 8, 1961, the product of writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby. And since that date, it's been one of the most important and one of the most intensely analyzed comic books of all time. This year, Marvel has even commissioned over 20 artists to re-draw the entire issue, page-by-page and panel-by-panel in a comics version of a cover song called Fantastic Four Anniversary Tribute #1.

Yet still, mysteries endure.

"It's a significant piece of work, and the first building block of everything that Marvel has become," says Marvel senior vice-president and executive editor Tom Brevoort. "And part of what makes this book so fascinating is that there are still things about it that no one really knows for sure."

Fortunately, people including ourselves have been investigating those mysteries. Brevoort has done some sleuthing of his own. Superfans have chimed in. Not all the dusky corners have been illuminated yet, but we can certainly start to shed some light on some of the enduring mysteries of Fantastic Four #1. Such as…

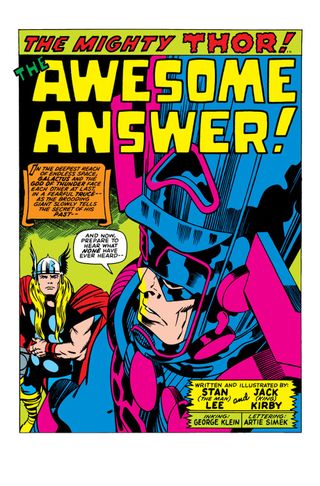

Who inked Fantastic Four #1?

Short answer: George Klein.

Longer answer: George Klein, but it took 50-plus years to figure that out.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

For decades, Marvel ran no inker credit on Fantastic Four #1 in its many reprints such as Marvel Masterworks. But in the early '10s, Masterworks editor Cory Sedlmeier finally made it official: Klein is the inker of both Fantastic Four #1 and #2.

Sedlmeier researched the issue and looked at evidence presented by a number of art experts. Primary among these experts is Dr. Michael Vassallo, who runs the Timely-Atlas-Comics blog and is generally considered the foremost expert in Atlas and early Marvel Comics art. Vassallo spent years poring over thousands of pages of art samples, analyzing different inkers over penciler Jack Kirby.

For his part, Sedlmeier is convinced this mystery is put to rest.

"Michael Vassallo has giant binders full of individual artists' work," Sedlmeier says. "He walked me through a variety of the Klein inking 'tells' with some aspects of his style that are apparent in Fantastic Four #1 showing up in Klein's work all the way back to '40s work like Venus."

The method by which Marvel 'awards' a retroactive credit is interesting in itself.

"The process, such as it is, is that when evidence comes up, the knowledgeable people here - Jeff Youngquist, Cory Sedlmeier, me, whoever else may know - talk about it and we weigh it and see how real it is," Tom Brevoort says. "It really comes down to best guess and weighing the evidence we have."

'I was there' evidence is given particular weight. Even though the original books carried no inker credits until Fantastic Four #9, Marvel has noted Sol Brodsky as the inker on #3 and #4, Joe Sinnott on #5, and Dick Ayers on #6 through #8 for decades.

"Typically when a guy shows up and says, 'I did that,' we tend to buy into that, absent compelling evidence to the contrary," Brevoort says. "In most instances, people were still alive at the time to confirm that they did it. Sol Brodsky confirmed that he inked issues #3 and #4 back in the '60s. Joe Sinnott inked #5, and a little bit of #6. #6 is credited to Dick Ayers, because Dick did most of it. Joe started on it and inked a couple of figures before he turned it back in because he had another, more pressing job. You can see those figures in the book."

Dick Ayers is a North Star in matters such as this. He kept complete, meticulous logs of all the work he did for decades.

"Dick Ayers issues are super-easy to figure out," Brevoort says.

But the rest is detective work. Remember, this was 1961. Comics were largely a churn-'em-out, on-to-the-next-one business. Few people felt they were important. Until Stan Lee. Lee treated his comic books with respect, and started listing credits including inkers and even letterers with Fantastic Four #9.

"That was incredibly important," the late Stan Lee told Newsarama previously. "I was trying to make the stories seem as if they had greater status. You go to a motion picture, and you don't just see the name of the star. There's also the director, the producer, all the co-stars, the lighting guy, and so forth. So I thought, 'Let's make our stories look more important; let's give as many credits as we can.'"

Was Fantastic Four #1 written in reverse?

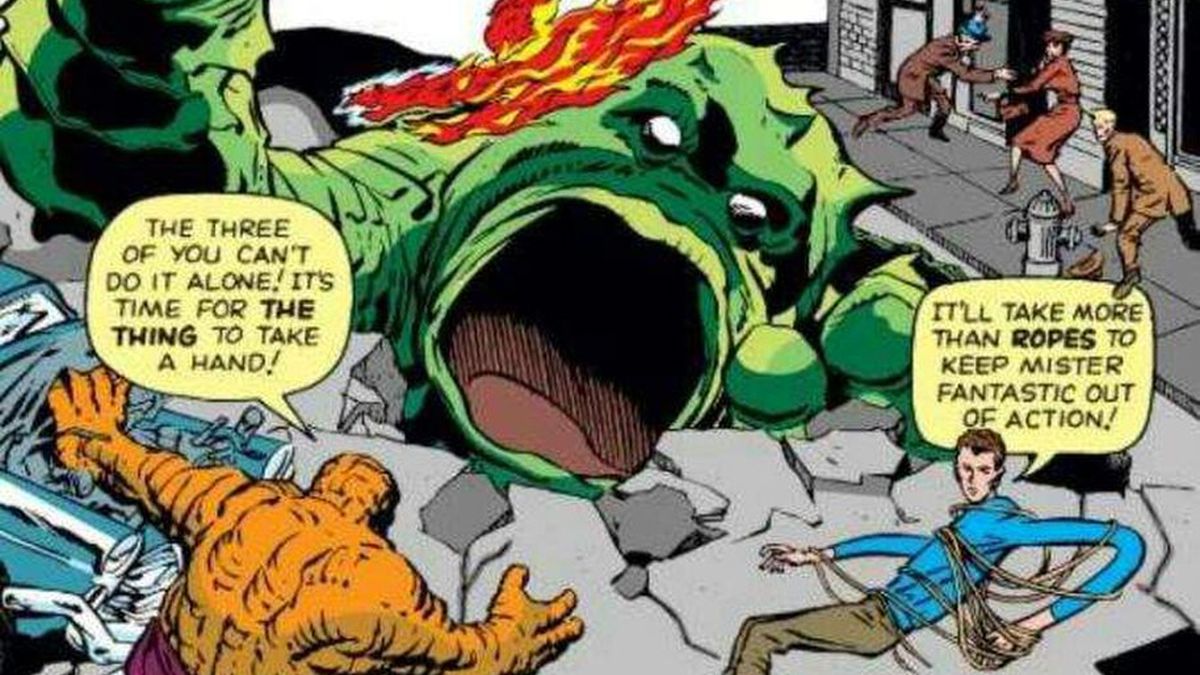

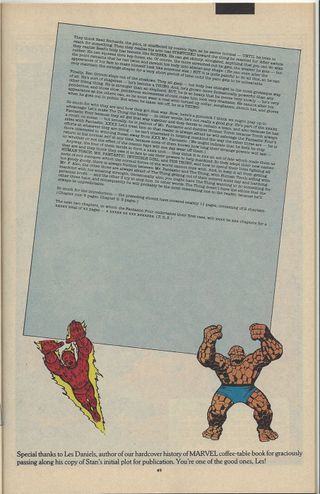

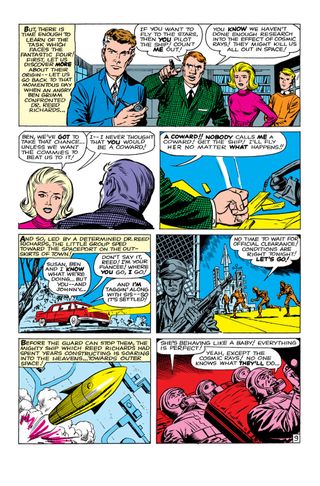

We've all read it: Four mysterious figures with fantastic powers appear, and we're given their backstory of cosmic rays imbuing them with those powers. Then, a massive battle with the Mole Man and his giant underground monsters ensues.

But what if the Mole Man stuff was written first?

"We accept the experience as page one is first, and you go on from there. It's difficult to disassociate yourself from that experience," says Tom Brevoort. "I've heard the arguments for it, and there's a really compelling case to be made that maybe everything from that Mole Man splash to the back of the book was designed as a thing that would have ran in one of the monster books, maybe as a pilot for the series, maybe as a one-off. And then when they decided to make it its own book, they added the origin at the front."

It seems mind-boggling to think of Fantastic Four #1 in this way today because, well…it has the weight of being Fantastic Four #1. But think in 1961 terms: Comic books were a slapdash business, and publishers and creators were tossing anything they could out there to see what would stick. Remember, Spider-Man's first appearance in Amazing Fantasy #15 was a mere 11 pages long. Thor's debut in Journey into Mystery #83 was 13 pages. Anything's possible.

Brevoort admits it's all conjecture, but he's tantalized by the possibility.

"Why are there chapter titles without chapter numbers? Why do they reveal the Thing, and then bundle him up to reveal him again? Even when the Torch first flames on in the back half, it's treated like 'This is a thing you haven't seen before as a reader' despite the fact that there's a whole sequence earlier. It really does look to me, with a trained eye, like the first half of the book and the second half were done independent of each other."

There are two massive pieces of evidence that would tend to shoot holes in the back-half-first theory.

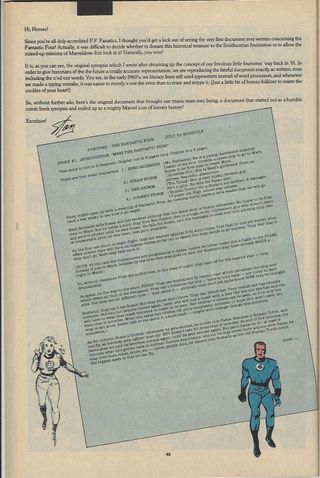

First, Marvel printed Stan Lee's original synopsis for Fantastic Four #1 in the thirtieth anniversary Fantastic Four #358. The synopsis clearly lays out the issue front to back. The page counts do not add up - Stan called for a intro of 11 pages, and the intro and origin sequence ran 13 pages. But again, slapdash business.

Roy Thomas was an early comic book historian, and became Marvel's second editor-in-chief after Stan Lee departed the position. He joined the House of Ideas in July, 1965, and he saw Stan's Fantastic Four #1 synopsis.

"I was interested in comics history, and Stan was probably surprised that I cared," Thomas says today. "He brought it in one day, and said he'd run across it at home. I didn't know it existed at that point. I had seen his plot for Fantastic Four #8 by that time, a couple years earlier. It's hard to say when I saw [the Fantastic Four #1 plot]. Late '65 at the earliest, early '66? Somewhere in there."

Thomas cannot speak to the specific content of the plot, but he certainly had something in his hands.

"I took a look at it, and gave it back to him later that day," Thomas says. "We didn't have a Photostat machine at that time, so I didn't get a chance to make a copy. I don't have a specific memory of what was on it, but I do remember it was the plot to the first half of Fantastic Four #1. There's no reason to believe it's not the same thing Marvel ran in that FF anniversary issue, but I couldn't swear to it."

The second massive piece of evidence? Stan Lee himself.

The story is legendary by now: Stan was at odds with his publisher, Martin Goodman. Goodman wanted thin stories with basic plots and not much on characterization. Stan was tired of cranking out simple fare, and was ready to quit. Stan's wife, Joan, suggested that if Stan was ready to quit, he might as well do a book the way he wanted to. The worst that could happen was that he'd get fired, and he was looking to leave anyway. Stan wrote Fantastic Four #1 the way he wanted to, with depth, humanity, and characters who were wildly three-dimensional. And he wrote from page one on.

"I did the issue in the order you read it," he told Newsarama in 2017. "I thought of the characters, and after I had them, I figured they had to fight somebody, and then I came up with Mole Man."

Was Fantastic Four #1 snuck in under the distributor's nose?

Before Marvel Comics was Marvel Comics, it was Atlas Comics. In 1957, it was cranking out 70+ titles (all under the editorship of Stan Lee!), some monthly, some bimonthly, and a few one-shots. Then, chaos hit.

Atlas was also a distribution company, and distributed its own comic books. But a change in business plan led to a new distributor, American News Company, which promptly went out of business six months after Atlas signed on. Publisher Martin Goodman had to scramble to get a new distributor, Independent News Company, which was coincidentally... owned by National Periodical Publications, the parent of DC Comics.

Independent News Company was willing to take on Atlas' business, but they weren't too crazy about allowing a robust competitor to DC. So the 70-ish title load went away, as they limited Atlas to eight books a month. Lee and Goodman chose to use that allotment to publish 16 bimonthlies. And so, from 1957 on, Atlas was limited in how many books it could produce for distribution. Until Fantastic Four #1. Although the exact shipping history of Atlas titles circa 1961 is a tad sketchy (more on that in a future article!), many sources including Steve Duin and Mike Richardson's excellent Comics Between the Panels refer to Fantastic Four #1 as a seventeenth title. Tom Brevoort agrees.

"I think it was definitely Goodman trying to push through as much as he possibly could," Brevoort says. "He basically figured they weren't going to pay attention."

Superheroes had just started to click again with the revival of the Flash at DC. And Goodman likely wanted in.

"Goodman's philosophy was 'Find out what's popular, produce a shit-ton of it for a period of time, rake in the dough, and get out of Dodge before everything crashes,'" Brevoort says. "Martin was a hustler, and hustlers hustle. I'm pretty sure he would try to sneak one more out, make one a monthly, see if they noticed, push the envelope a little further. I'm pretty sure a lot of that just became standard operating procedure for him."

Again, the precise publishing regularity and history of Atlas at the time was a little erratic. For his part, Stan Lee was just trying to make all the trains run on time.

"I wasn't aware of Fantastic Four being a sixteenth issue, a seventeenth issue, or anything," Lee told Newsarama previously. "I was just doing the books!"

But there's a very solid chance that the bedrock of the Marvel Universe was an end-run around Marvel's distributor of the day.

Where is the original art for Fantastic Four#1?

Strangely, some of the mysteries of Fantastic Four #1 could be solved if we could examine the original art. Pages from #3 are known to exist, but pages from #1 and #2 have never surfaced, despite vague rumors that some may exist in 'deep collections.'

"Assuming that the Fantastic Four #1 art hasn't been lost or destroyed over the years, which it may very well have been, there's a lot you could learn if it ever became public," says Tom Brevoort.

Artists typically wrote the title of the book they were working on at the top of the page. "Fan. Four" might stand in for an issue of Fantastic Four, and "Journey" for an issue of Journey into Mystery. If the Fantastic Four #1 pages said "Amaz. Adv." or "Suspense" at the top, that would be a strong indication that the theory that first Fantastic Four story was indeed intended for another book and perhaps written in reverse is correct.

Brevoort points to discoveries made when Amazing Fantasy #15, the first appearance of Spider-Man, surfaced and was donated to the Smithsonian Institute.

"You can study it and discover things like, 'Oh, there was originally a different Spider-Man logo here, and look, in that panel, [artist Steve] Ditko had originally penciled another figure in there and took it out in the inks,'" he says. "There are all kinds of things you can't know without this stuff surfacing."

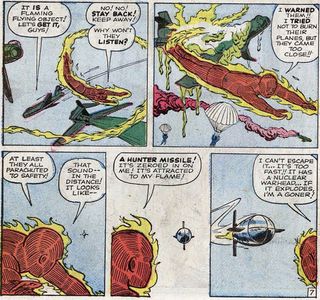

Another tiny mystery: Marvel reprinted the origin sequence of Fantastic Four #1 (1961) for the first time in Fantastic Four Annual #1 (1963). In the interim, the Human Torch had gone from a blob of fire to a more 'human' torch, so those pages were updated to show the torch in that more human form. We know that Sol Brodsky re-drew those Torch figures, and a theory exists that he may have done it right on the original Fantastic Four #1 boards. If so, we'd know that the art existed at least until 1963. But even Marvel's go-to reproduction guy doesn't know for sure.

Michael Kelleher is Marvel's official recreation artist for Marvel Masterworks and other vintage collected editions. Kelleher calls himself a "human scanner," sometimes doing digital pixel-by-pixel touch-ups on old, damaged artwork scans and sometimes re-drawing images, painstakingly mimicking Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, or Don Heck, and the line weights of multiple inkers.

"That could be true," Kelleher says. "But it's just as likely, and we see this quite a bit, that people draw over copies of the original art or the original film. That type of thing, I've actually seen."

Kelleher says he's never seen a page of original art from Fantastic Four #1. But mysteries remain, even in the copies.

"I remember in the scans of the cover I got for Fantastic Four #1 - I can't recall if it was film or a photocopy - there were characters missing in the background, and we had to go back in and digitally re-insert them," he says.

Film or stats held more value to publishers back in the '60s. You could do reprints from them, and once made, the originals were just an intermediary part of the production process.

"We thought so little of it that believe it or not, sometimes we'd give a page to a kid who came up to deliver lunch from the drugstore," Lee said in 2017. "Instead of giving him money as a tip, we'd say, 'Here you go, kid, have a page of artwork.' Now I'm certainly not sure that happened with pages of Fantastic Four #1 in specific, but we didn't realize these pages had any value at that time."

Roy Thomas is up in the air as to if Brodsky did the Fantastic Four Annual #1 changes on the original art or on another medium.

"They had some original art around then," Thomas says. "The only other thing they would have had were these stat rolls, these old black-and-white Photostats rolled up like scrolls from the Alexandria Library! A lot of those were in a little office, just shoved back in a corner against a wall."

But was the Fantastic Four #1 original art still there in 1963?

"Sol was a good enough artist, he would have just whited out what was there and turned it into something that reflected the change," Thomas says. "But there's no way to really tell, that I know of, if it was done on the original art or the Photostats."

Bottom line: No one knows where the original pages of Fantastic Four #1 (or #2) are. But if they are ever found, some mysteries might cease to be mysterious.

"If those boards exist and come out, you'll have a much better chance of putting things together," Brevoort says. "What's the title of the book that's written at the top of all those pages? Are those pages sliced apart, cut up, and re-jiggered as they often were in those days? What kind of art corrections and stuff like that were done? Seeing the original pages…that's a Rosetta Stone."

Brevoort is not the only one who wants to find the key.

"I wish I could figure all this stuff out!" Roy Thomas says. "Each one of these questions is like a little Holy Grail! I wish I was paying more attention back in 1965."

If you've made it this far, you're definitely a fan of the Fantastic Four. So if that's true, make sure you've read the best Fantastic Four stories of all time.

—Similar articles of this ilk are archived on a crummy-looking blog. You can also follow @McLauchlin on Twitter

Most Popular