Resident Evil is no stranger to mutation. Capcom reflects the unsuspecting citizens of Raccoon City in this respect, genetically morphing over time in response to viral and environmental factors beyond its control. But where those caught up in the aftermath of the Mansion Incident can blame the T-virus for slow decay and eventual regeneration, Capcom doesn't have an Umbrella Corporation of its own to point to.

Resident Evil has endured a perpetual cycle of trial and error since it made its debut 25 years ago. It has adapted to change and forced the industry to change alongside it. To look at the evolution of Resident Evil's combat over the last 25 years is to look at a series that isn't afraid to innovate and iterate. The publisher hasn't always been successful in this endeavor, but its willingness to at least try is likely a reason why the Resident Evil series is as potent today as it was when it made its debut in 1996.

Glass Tanks

Key Games: Resident Evil (1996), Resident Evil 2 (1998)

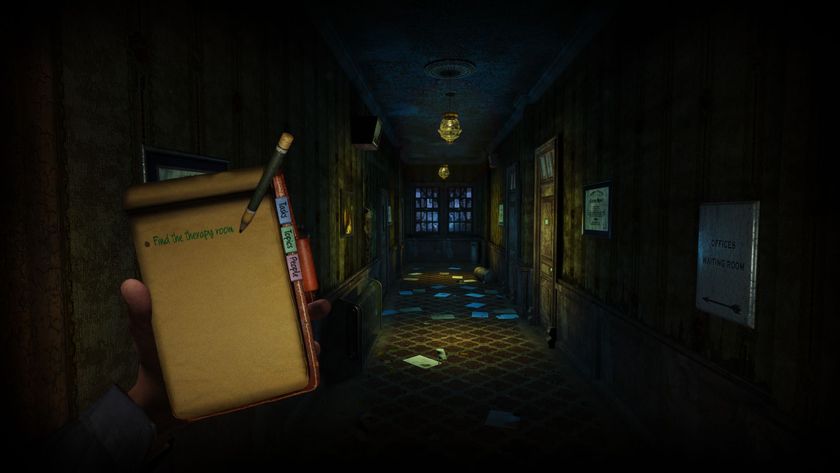

The horror of the early Resident Evil games wasn't derived from the monsters that lurked in the shadows of the Spencer Estate and Raccoon City, but in your attempts to circumvent them. Capcom utilised fixed camera perspectives to bring a sense of cinematographic authorship to each of its dilapidated buildings, claustrophobic corridors, and underground facilities, and your capacity to navigate them was limited by design; Chris Redfield, Jill Valentine, and Leon S. Kennedy handled like glass tanks moving through blood-soaked mud.

Left and right inputs of the directional pad rotated the characters in place, up and down let them move forwards and backwards relative to the camera, all as a single clawing hand forever threatened to send you hurtling back to the last typewriter you were able to thread an ink ribbon into. Lack of mobility was key to the vibe of Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2, but the games ultimately found success by forcing you to stand your ground. Should you decide to load a shell into a chamber, you were forced to commit to the action; feet planted, shoulders relaxed, and weapon drawn, you could fire straight ahead or tease the barrel of the weapon ever so slightly on a vertical axis. These limitations helped instill the idea that combat should be treated as a last resort.

Adapt to survive

Key Games: Resident Evil 3: Nemesis (1999), Resident Evil – Code: Veronica (2000)

Resident Evil 3: Nemesis might kick-off just two short months after Jill Valentine survived the nightmare of the Mansion Incident, but she was able to learn a couple of new skills while lying low in Raccoon City. Resident Evil 3 is the series' first flirtation with an expanded move set, as the former Special Tactics and Rescue Service member is able to perform a 180-degree spin, push away encroaching enemies, and dodge attacks entirely, should she get the timing right. Some players balked at the improved mobility, although it was necessary to survive the threat of Nemesis.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

If Resident Evil 3 flirted with action, Code: Veronica unabashedly embraced it. While Claire and Chris Redfield's adventure came equipped with Resident Evil's signature controls and interface, it introduced real-time 3D environments and a more dynamic camera. As a result, combat was faster and more aggressive. One boss battle against a mutilated Alexander Ashford even has Claire dancing between third-person movement and first-person aiming with an MR7 sniper rifle, a hybrid design that would later be used in Resident Evil: Dead Aim, although the need to target enemy weak points would persist through just about every Resident Evil game that followed.

Gradual Evolution

Key Games: Resident Evil Remake (2002), Resident Evil Zero (2002)

Resident Evil carried one valuable lesson into the '00s: sometimes a bullet to the head just isn't enough – in fact, it can make an already precarious situation 100% worse. In 2002, Capcom released a truly fantastic remake of Resident Evil for GameCube, overhauling the visuals and refining the controls that once helped define survival horror. A new enemy type was introduced, the Crimson Head zombies, which would cause downed enemies to regenerate into red-headed nightmares that made your mission infinitely more challenging. To prevent Crimson transformation, corpses had to be set alight or decapitated entirely, and this heightened focus on the methodical execution of your enemies became an integral part of the series moving forward.

In many ways, Resident Evil Zero followed the core formula faithfully – a prequel set before the Mansion Incident that cast a light on what happened to the S.T.A.R.S. Bravo Team in the Arklay Mountains – but it did add a new wrinkle. A 'Partner Zapping' system was introduced, letting players switch control between rookie agent Rebecca Chambers and convicted criminal Billy Coen to solve puzzles, exchange resources, and be better equipped to tackle threats. This system wasn't properly utilized again, but it was an interesting idea all the same.

Exploring New Perspectives

Key Games: Resident Evil Survivor (2000), Resident Evil: The Umbrella Chronicles (2007)

Resident Evil 7: Biohazard demonstrated how powerful Resident Evil could be when cast from a first-person perspective, but it wasn't the first game in the series to experiment with the more intimate camera angle. That's on Resident Evil Survivor, the light-gun game released in 2000 that took players for an on-rails tour of the timeline that is better left forgotten. The first wave of light-gun games weren't all that successful, as Capcom struggled to find unity between Resident Evil's survival horror roots and an on-rails shooter's need to keep the action fast and frantic.

Still, Capcom persisted. Resident Evil: Dead Aim arrived in 2003 with a strange hybrid design of third-person movement and first-person combat. That looked to be the end of it until the Nintendo Wii released, and Capcom finally realised its dream of making Resident Evil function in first-person. The Umbrella Chronicles and its sequel, The Darkside Chronicles, were surprisingly fun runs through Resident Evil's history, and taught a lesson that Capcom would remember long into the future: shooting enemies in the head is even better when you're up close and personal.

Over The Shoulder

Key Games: Resident Evil 4 (2005)

It's difficult to overstate just how important Resident Evil 4 was – it fundamentally altered the composition of the third-person shooter, and in a way that can still be felt in genre games to this day. The camera was repositioned from corners of the environment and fixed tightly to the shoulder of a world-weary Leon S. Kennedy, but the need to plant your feet and fire from a stationary position remained. This small decision made encounters feel suffocating – the structure of the third-person shooting evoking claustrophobia rather than the environments, which were wider and promoted more verticality to better support dynamic enemy AI.

Given the hordes you faced, aiming for weak points became vital. The C-stick of the GameCube controller used to tease a weapon's laser sight towards legs, hands, and heads – enemies would react accordingly should you hit the appropriate appendage – giving you limited time to create space, evade attacks, and line up your next shots, and the sound of a skull shattering in Resident Evil 4 remains one of the most satisfying audio cues in gaming. Resident Evil 4 also introduced weapon customization and a degree of variety not seen in the series before – along with ridiculous close-quarters combat – that would be a mainstay moving forward, and taken to their logical conclusion through Resident Evil 5 and Resident Evil 6

Into The Action

Key Games: Resident Evil 5 (2009), Resident Evil 6 (2012)

The foundational principles of Resident Evil 4's combat would guide the two mainline games that followed with varying degrees of success. While Resident Evil 4 shifted beyond survival horror and into an action-horror configuration, it was still a game that forced you to wrestle with the limitations inherent to its movement mechanics and combat systems. Resident Evil 5 struggled as it introduced cooperative ambitions, faster pacing, and blockbuster scenario design – the standoffs didn't sit comfortably with an inability to move and shoot, particularly in its wider spaces designed for two players.

Resident Evil 6 overcame this hurdle – finally letting players move and shoot – but immediately ran into others, stumbling and never recovering. Ammo and items were plentiful, setting the stage for an action-focused installment that waved goodbye to horror entirely. The action was faster but less precise, with the laser sight of its immediate predecessors stripped from play. Mobility was greatly improved, letting you slide, dodge, and roll around environments to avoid clawing zombies, but it felt flimsy and unintuitive. Resident Evil 6 was the natural endpoint of Resident Evil's flirtation with the action genre, and it's no surprise that it would be the last to feature such free-flowing movement and combat.

New formula

Key Games: Resident Evil: Revelations (2012), Resident Evil 2 Remake (2019)

Recognizing that corners of the fanbase were becoming dissatisfied with the direction Resident Evil was headed, Capcom attempted to dial back into the style of play introduced by Resident Evil 4 and enacted a more gradual iteration from its foundational design. Resident Evil Revelations embraced a stripped back combat system to create tension from limitation like the best games that came before it, introducing little more than a dodge mechanic that would give careful players an opportunity to reposition.

Resident Evil 2 Remake continued this line of thought to its natural conclusion. A total reimagining of Resident Evil 2 for a modern audience, it felt as if it had taken the best elements of the third-person Resident Evil games and rooted them within the suffocating terror of survival horror once again. It's a pure distillation of what made Resident Evil work in the nineties – a lesson in restraint that succeeds because of the limitations it puts upon the player in combat, forcing you to fight with limited mobility and ammunition against growing hordes of relentless enemies.

First-Person Action

Key Games: Resident Evil 7: Biohazard (2017), Resident Evil Village (2021)

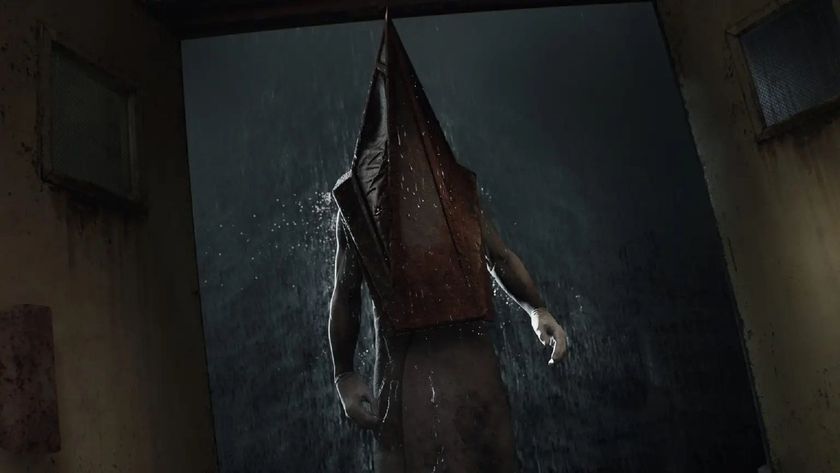

In the immediate aftermath of Resident Evil 6, it was clear that something would need to change if the series were to have a future. What we received in Resident Evil 7: Biohazard wasn't a reorientation of the classic Resident Evil formula, but a reinvention of it. For the second time in Resident Evil's history, the publisher enacted a daring perspective change, this time fixing the camera behind the eyes of a brand new protagonist; Resident Evil embraced first-person action, and the series felt fresh again for the first time in a decade as a result.

Combat was slow and methodical once more, with the player encouraged to treat shooting and movement as separate actions due to your limited mobility, the claustrophobic spaces you were moving through, and the limited accuracy of the small arsenal of weapons you were able to get your hands on at the Baker Estate. Capcom appears to be smartly evolving these first-person systems for the highly-anticipated 2021 sequel, with Resident Evil Village introducing iterative defense mechanics to help give Ethan an edge in the more open spaces of Castle Dimitrescu.

Want to learn more about the history of Resident Evil? Then you'll want to read our ultimate guide to the Resident Evil games, tracking every major release over its 25 year history.

Josh West is the Editor-in-Chief of 12DOVE. He has over 15 years experience in online and print journalism, and holds a BA (Hons) in Journalism and Feature Writing. Prior to starting his current position, Josh has served as GR+'s Features Editor and Deputy Editor of games™ magazine, and has freelanced for numerous publications including 3D Artist, Edge magazine, iCreate, Metal Hammer, Play, Retro Gamer, and SFX. Additionally, he has appeared on the BBC and ITV to provide expert comment, written for Scholastic books, edited a book for Hachette, and worked as the Assistant Producer of the Future Games Show. In his spare time, Josh likes to play bass guitar and video games. Years ago, he was in a few movies and TV shows that you've definitely seen but will never be able to spot him in.